THE UTILIZATION AND PATIENT DEMOGRAPHICS OF PATIENTS REHABILITATION PROGRAM

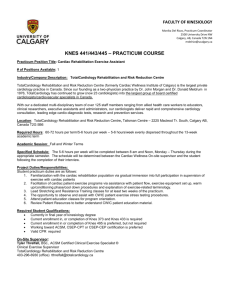

advertisement