A METHODOLOGY FOR SUSTAINABLE COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT

advertisement

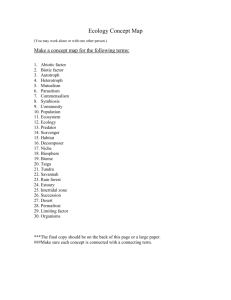

A METHODOLOGY FOR SUSTAINABLE COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT A CREATIVE PROJECT SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE BY KEENAN W. GIBBONS COMMITTEE CHAIRPERSON: JOSEPH C. BLALOCK, JR COMMITTEE MEMBER: SIMON BUSSIERE COMMITTEE MEMBER: DR. STEPHEN KENDALL TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION PAGE INTRODUCTION 3-4 SITE ANALYSIS AND DOCUMENTATION 5-21 PRECEDENT RESEARCH 22-33 DESIGN PROCESS 34-49 DESIGN PROPOSAL 50-63 CONCLUSION 64-67 BIBLIOGRAPHY 68-71 INTRODUCTION As fossil fuel and depletable resources become scarce and the global population exponentially grows, sustainable systems will become increasingly vital to human survival. Mitigating depletable resource dependency is the first step toward attaining sustainable survival. If food is grown in a person’s backyard, that person no longer has to drive to the grocery store to purchase food that is grown, packaged, transported, and then stored from all around the world. If portions of habitable land are protected as natural preserves at the onset of proposed development, then aesthetically pleasing natural cleansers are created to self-regulate the pollution generated by humanity. If pedestrian-oriented infrastructure is embedded into the framework of proposed development, then society is no longer designing for automobile dependency. Conventional Midwestern community sprawl has been fueled by conventional planning, which typically aims for maximum capacity and efficiency for quickly generating revenue. This manifests homogenous human dwellings part of systems that break down over time, and dwelling units constructed at densities solely for the finan- cial aggrandizement of the land developer. Establishing an understanding of how conventional development can be reoriented for holistic sustainable development became the driving force for creating a design methodology for community development in this creative project. A 41-acre open agricultural site at the fringe of urban sprawl was selected for a proposed sustainable community in west Muncie, Indiana. The site is located on the corner of West Jackson Street and North Morrison Road—two heavily trafficked vehicular corridors into the city. The site is neighbored INTRODUCTION_Continued by existing residential neighborhoods, and currently owned by a local land developer. groups, ecology, and healthy living was the desired design outcome. The project began with comprehensive site analysis and documentation. After a thorough understanding of the site was established, existing Midwestern precedents similar in scope were dissected to identify successes and failures through quantitative and qualitative data. The assessed strengths of precedent research became a composite framework for the land use capacities of the proposed site. An agrarian-based community, promoting diverse user 4 SITE ANALYSIS This section justifies site selection for a proposed site for sustainable community development. This is accomplished by viewing the site from a variety of scales and applications. Google Earth satellite imagery, along with existing public transportation maps and GIS data evolved into original graphics that helped to reveal contextual opportunities and conflicts, while effectively justify the site for proposed development amidst engulfing urban sprawl. At the southeast corner of the site appears a greenish rectangle. An existing resident currently resides in this area, but was hypothetically considered to be leaving for purposes of developing the entire proposed site. The parcel of land is zoned in as a single piece of property in its entirety, and was highlighted with color contrast from the black and white background to indicate the proposed site. SITE ANALYSIS_Figure Ground The figure ground illustrates the proposed site (Faded in color at center) in reference to surrounding development. The outcome reveals the dark urban core of downtown Muncie, IN and the sprawl moving northwest. This trend justified proposed sustainable development for the existing open agricultural site. roads and buildings waterway ch it tt d hia white r iv e r 6 SITE ANALYSIS_geographic information system data ORANGEWOOD LE GE ND HOLMBROOK CY MORRISON SS SN O W M A EN N IO CT RE SO DI CK G RE AL JA SAYBROOK SWISS CHURCHILL ER CHALLENGE ER WO O D GE T HIA SH WE S T CAN TER KNO IT TD MIL L W AY NA AI DR Earthwork within existing contours would achieve irregular, curvilinear forms and lowimpact development. OF N CH TM B ER BENTON Y N GE Existing topography creates a natural gully for water to collect in the southeast corner of the site, before entering Hiattt Ditch and the White River. LE C GA PO LL B UR Y C AR A DIN L JA C CA RD INA K SO N RIV ROAD 5' CONTOUR PARCEL 0 250 500 VI E ER S W IDE L Legend STREAM ND 1,000 Feet 1,500 X 7 SITE ANALYSIS 5-mile radius mcgalliard ling hee n. w SITE e r hit ver i w w. ja ck son n. morrison Context •NW Muncie •<3 miles from site to downtown Muncie •<1.5 miles from site to BSU campus and Ball Memorial Hospital downtown muncie 8 SITE ANALYSIS mcgalliard 1-mile radius north morrison Context •<1 mile from site to Walmart and McGalliard •≈1 mile from site to White River Greenway st j SITE ack son hia tt di tc h we white river 9 SITE ANALYSIS .25-mile radius Context •41 acres •Open agricultural land SITE n. morrison w. ja ckso n 10 SITE ANALYSIS Ma in Downtown Wal nut 10 hi te Riv e ® r 16th White Ri ver Macedon ia Madison W Meeke r Madison yt Ho ton Manhattan 9 Hac kley Penn Beacon 11 ing Mock 12 11 Burl Me moria l Hackley Port Me moria l Cowa n 29th ison 12 Mad Clark Me moria l 8 Macedonia 8th 10 Pen n 8 th J a c k s on K irby W illa rd e 2 7 P owe rs 12 12 W y s or 7 Jackson Hackley Liberty Cou ncil C ha rle s r White Rive Kilgor Hodson Walnut McKinley Tillotson Nichols Stradlin g Morrison g Kin Kilg W h i te R i v e r 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 14 16 er Grande ore 57 Riv ML 2 L owe ll Manh attan er Riv ite Wh i te U nive rs ity Jackson 2 Wh Gavin Ball Memorial Hospital H ighla nd H ighla nd R ive rs ide ® 1 Ball State University 2 Ball State Jackson 3 Northwest Plaza 4 Mall 5 Whitely/Morningside 6 North Walnut 7 East Jackson 8 Burlington 9 Industry Willard 10 Heekin Park 11 Southway Centre 12 Ivy Tech 14 Riverside/Rural King 16 WalMart Minnetrista ng 1 57 e eli Peachtree Jackson wa y Wh Tillotson Centennial 3 1 Garver Bro ad Walnut el 14 Route Names and Numbers Gra nv ille Oakwood Everb rook Ma rleo n Chadam Lane Morrison Rosewoo d Beth 16 Macedo nia Potential Transit Connections S tre e te r 4 6 Mc G a lliard Mc G a llia rd Elg in R oya le 7 NorthWest Plaza 6 nd 14 Muncie Mall Mc G a llia rd 3a el 3 57 Y a le SR ® 35, 4 MUNCIEMALL C la ra Beth US F s pas 16 e dg oxri 6 Airpark Belliare ue Purd Ontario By W oods E dge ncie Mu Superior (Modified from Muncie) ng e eli Wh A map of bus routes from the Muncie Indiana Transit System (MITS). The map includes existing bus routes and popular destinations in and around Muncie, IN. The proposed site (Indicated by dashed circle) was added to see its contextual proximity to existing public transportation and popular destinations. Munc ie B ypa s s S R 3 a nd 6 7 March 2010 11 SITE DOCUMENTATION Site interface of residential R4 community immediately north. The community is defined by driveway clusters of two dwelling cells per duplex, and two duplexes per driveway. 12 SITE DOCUMENTATION Site interface of residential R4 community immediately north. Existing feed corn can be seen on the right, while shared duplexes are apparent to the left. 13 SITE DOCUMENTATION Site panorama looking south from high point of site, at the interface of residential R4 community immediately north. Existing site land use is for agricultural feed corn production. 14 SITE DOCUMENTATION Photograph looking north on Morrison Road. Notice an absence of pedestrianoriented circulation. Existing feed corn can be seen on the left, and vegetation of a private resident is apparent on the right. 15 SITE DOCUMENTATION Photograph looking south on Morrison Road. The proposed site can be seen at right. 16 SITE DOCUMENTATION Photograph looking east on Jackson Street. 17 SITE DOCUMENTATION Photograph looking west on Jackson Street―often a heavily trafficked arterial corridor into Muncie. This would inform proposed site gateways. 18 SITE DOCUMENTATION Photograph of gateway at West Jackson Street for shared duplex housing in neighboring R5 residential community immediately west. 19 SITE DOCUMENTATION Photograph south along street of shared duplex housing in neighboring R5 residential community immediately west. 20 SITE DOCUMENTATION Photograph of shared duplex housing in neighboring R5 residential community immediately west. 21 PRECEDENTS This section outlines existing precedents that were evaluated on strength of sustainable characteristics as relevant to the scope of proposed site development. Midwestern agrarian communities and sustainable agricultural operations were of greatest influence. Research focused on precedent methodology, planning, temporal success, systems, goals and objectives, capacities and land use, user groups, scale, and relationships therein. PRECEDENTS Michigan State University Student Organic Farm • East Lansing, MI • 10 acres • 16,000 sf passive solar greenhouse space • 2,000 sf heated greenhouse • 4-season, 48-week CSA provid ing fresh and stored vegetables to over 100 families, (Additionally herbs, fruits, and flowers during summer) • 2/3 acre permaculture site including 60 laying hens, 5 beehives, sugar maple orchard, and mushroom production • Michigan State University Organic Farmer Training Program • MSU Outreach program educates growers statewide on year-round production utilizing passive solar (Michigan) 23 PRECEDENTS_E-GATE 25m2 of intensive horticulture = basic sustenance per person E-Gate can support approximately 4,500m2 of intensive horticulture = food for 160 people (Adapted from Bussiere) 24 PRECEDENTS E-GATE Public Realm • Melbourne, Australia • 45:55 Green:Grey • Pedestrian oriented • Elementally powered • Food production capacities (Adapted from Bussiere) Design priniples •Site •Circulation network •Hierarchy of open space •Tree strategy •Public realm •2k circuit •Bicycle strategy •Water systems •Lattice of open spaces •Journey Lines •Vehicular mobility •Rooftop strategy 25 PRECEDENTS Land use • 655 acres total • 346 acres (52%) devoted to prairies, pastures, farm fields, gardens, marshes and lakes • 131 acres (20%) house lots • 452 acres (69%) open space (Traditional suburban development 70% house lots) Dwellings • 317 single-family homes • 16 different home types • 4 types of lots: 1 Village home-sites in a neotraditional village with a Market Square and Village Green 2 Prairie sites, arranged in groups of eight, with views over open fields reminiscent of old farmsteads 3 Meadow sites face large, landscaped common areas in front and overlook fields, marshes or lakes in back 4 Field sites border farm fields (Adapted from Ruano 135) 26 PRECEDENTS Land use [1987] • 655 acres total • 346 acres (52%) devoted to prairies, pastures, farm fields, gardens, marshes and lakes • 131 acres (20%) house lots • 452 acres (69%) open space Land use [2010] • 678 acres total • 470 acres (69%) devoted to prairies, pastures, farm fields, gardens, marshes and lakes • 135 acres (20%) house lots • 73 acres (11%) commercial and industrial • 468 acres (69%) open space 1987 2010 700 600 acres 500 400 300 200 Dwellings [1987] •317 single-family homes •16 different home types •4 types of lots e l op en sp ac er cia co m m lo ts e us ho na tu ra la to ta l re a 100 Dwellings [2010] •362 single-family homes •36 condos, mixed-use commercial core 27 PRECEDENTS_Prairie Crossing_Goals and Objectives Environmental protection and enhancement • 350 acres legally protected from future development • Part of Liberty Prairie Reserve, over 5,000 acres of publicly and privately held land • Greenways and houses designed to protect wildlife and promote midwest character A sense of community • Homeowners Association • Volunteer stewardship activities organized by Liberty Prairie Conservancy, which conducts environmental programs throughout the Liberty Prairie Preserve • Connections with other homeowners associations, public officials, and local businesses A healthy lifestyle • >10 miles trails, a stable, and large lake with beach and dock • Farm supplies fresh organic vegetables, flowersm and fruits • Individual garden plots are avail • Lake Forest Hospital built new facility onsite Economic and racial diversity • All races are welcomed • Mixed incomes and races are essential to the future of society • Some housing prices have been kept low to provide affordable housing in Lake County A sense of place • Aesthetics defined and inspired by prairies, marshes, and farms of the area • Streets are named after prairie plants and early settlers • House colors derived from warm tones of native landscape • Community buildings are a historic barn, schoolhouse, and farmhouse Convenient and efficient transportation • 1 hour from Chicago by train/car • Rail service to Chicago and O-Hare Airport from two adjoining site stations • Positioned within triangle of 3 major roads: Routes 45, 137, and 120 • Trails lead to train station, College of Lake County, University Center of Lake County, Liberty Prairie Reserve, Grayslake High School, and local stores and restaurants Energy conservation • Homes constructed to reduce energy consumption by 50% in comparison to new homes in the area • Designed to encourage walking and biking • Wind turbine provides farm power • New buildings of PC Charter School designed to LEED standards Lifelong learning and education • Charter school offers elementary education based on environmental curriculum • Informal learning through partnerships • Two colleges within 2 miles Aesthetic design and high quality construction • Highly accomplished professionals responsible for land planning and architecture Economic viability • Developed as a conservation concept demonstration model • Efforts always made to ensure project is economically feasible and budgeted for long-term success 28 PRECEDENTS Tryon Farms • Michigan City, IN • 170 acres, 75% (120ac) protected openspace • Dwellings ≈ 70 units • Dwelling sizes = 400 - 3,500 sf • One hour from Chicago • Commmunity newsletter • Wastewater wetlands treat blackwater in 7 days for farm use • 6 settlements comprised of various scales and densities housing • Tryon farm guesthouse (Adapted from Tryon) 29 PRECEDENTS Detached Clusters of Tryon Farms Woods settlement Woods settlement Farmstead settlement Wetland Farmstead settlement (Nomenclature adapted from Tryon) Wetland Overall site 30 SITE PROGRAM Preserve Residential Agricultural 12.5 acres 21% 10.0 acres n. morrison 29% 45% 19.1 acres Precedent research informed the initial schematic capacities for programmed land use of the proposed site (Right). w. ja ckso n 31 PRECEDENTS_Results Precedent research defined the primary land use capacities for the proposed site. A common pattern observed among all residentially rooted precedent case studies was a reversal of conventional design ratios. The Prairie Crossing precedent, particularly, validated this reversal through its design decisions, since Prairie Crossing was proposed in a comparable midwestern context, and since conventional midwestern land use trends were identified by the Prairie Crossing design team specifically for reorienting and reversing these capacities for a more sustainable form of community development (Ruano 135). And, sustainable community development was the ultimate intent of this creative project from its onset. The design team discovered that existing, conventionally proposed midwestern community land use capacities were about 70% residential space to just 30% open space (135). This ratio was then reversed for the land use capacities of the Prairie Crossing proposal (135). Instead, there would be 30% residential space and 70% open space (135). This was done to promote the healthy systems that result from larger areas of open space, and also with the idea that a congruent number of site inhabitants could still occupy the same space (135). This became the first set of capacities to be proposed on the site in this creative project. Furthermore, Prairie Crossing included an entrepreneurially supported agriculture operation, and a protected nature preserve. Hence, space was also set aside for agricultural operations and protected natural preserve within the loosely defined 70% open space of the proposed site. Thus, the three land use indicators seen in the site program (previous page) were defined as Preserve, Residential, and Agricultural. The actual capacities would be dictated by other precedents, and capacities would slightly deviate from the original constraints of the site program by the end of the project. Other precedents served other purposes, both implied throughout the design 32 process, and perceived throughout the design proposal. The Michigan State University Student Organic Farm played a key role in determining the volume of food and community supported agriculture shares that could result from 10-acres of intensive horticultural plots―including the support structures/outbuildings for staging day-to-day operations. Since 10 acres fulfilled weekly community supported agriculture shares for 100 families for a great portion of the year, 10 acres of the proposed site were, likewise, dedicated to agricultural production (Michigan). E-GATE provided an ideology for establishing capacities that are defined by a clearly defined site hierarchy of proposed site elements. This would most significantly inform the scales of the spatial relationships diagrams (See Design Proposal section). These diagrams used ratios found within the hierarchical scales employed in E-GATE to define three primary hierarchies of residential space, containing mutliple systems to also be hierarchically framed, therein. Precedentestimated ratios comparing the agricultural food production of a given area to the quantity of human lives that could be supported by it laid a groundwork for evolving the allotment gardens of the design proposal. housing clusters (Tryon). The proposed site also mimicked the idea of instilling community character by dictating site interfaces, and evolving diverse layouts via handmade collages. These collages and their correlating design decision matrix will evolve in the following section. Likewise, the Tryon Farms precedent significantly influenced the various dwelling aggregations that were deployed during the design process. The Tryon Farms master plan set out to achieve distinct community identities through diverse 33 DESIGN PROCESS This section outlines the design process undertaken after site analysis, documentation, and precedent research had been completed. The process began by developing a client narrative to establish user groups. Next, a design decision matrix evolved to visually organize and evaluate design decisions based on the interpreted responses of hypothetical user groups as outlined in the client narrative. A plotted hardcopy of the schematic capacities for site land use map accommodated development of a variety of land use aggregations, or schematic design alternatives assembled by handmade collages. The handmade collages became a valuable social tool for developing a collaborative design process between the client and designer. In a real-world scenario the simplicity of the handmade collages could be deployed during early phases of community development. The simplicity of the collages could be easily communicated to the client to accommodate their active, participatory role in the design process. Since the client in this project was hypothetical, the client narrative became the priority system to evaluate finished alternatives within the design decision matrix. Alternatives that exhibited the highest priority amongst user groups were identified, and in some instances isolated for their respective design decision(s), for eventual implementation on a finished design proposal. The first few pages of this chapter illustrate the aforementioned tools used for generating design alternatives, which are outlined in subsequent pages. DESIGN PROCESS_Client Narrative early Early in human life, the boy has two parents, and two siblings in his family of five. The family is active in the community and the children take part in extracurricular activities. One parent commutes to work, and both are very eco-conscious — sharing a hybrid automobile, strict about recycling waste, and getting recreational excercise when possible. One of the parents is also an avid gardener and lover of the outdoors, and encourages the participation of the children. middle The boy has grown into a man near the middle of human life. He has recently completed extended education, and lives independently. During school he accrued significant debt, but sold his old automobile to make ends meet financially while establishing a career. Since, he has relied almost entirely on bicycling or public transportation. The man is in a promising relationship, and would like to begin a family one day, but at the present is not completely rooted in one specific location. late Late in human life, the man has reached retirement and begun focusing on his final years. He lives with his longtime wife, and the last of their children moved out about two decades prior. The elderly man enjoys gardening, lowimpact outdoor recreational activities, and getting visits from his children and grandchildren. He and his wife share an old hybrid automobile, but increasingly rely on public transportation. They also like to stay active in the community, and are often engaged in local events and social gatherings. 35 DESIGN PROCESS 2 3 steel ruler x-acto® 1 t tex t no 100í 29% 11.6 acres 48% 21% 8.4 acres 19.2 acres n. morrison A scaled hardcopy of the initial schematic capacities for site land use map (Refer to page 31) was plotted at 1” = 100’. The hardcopy was measured and cut into various sizes of scaled squares, organized by color and coordinating proposed land use. These squares effectively maintained scale and capacity for experimenting with a variety of land use aggregations via handmade collages, and worked in conjunction with a design decision matrix. 0.5î x 0.5î 0.5î x 1.0î 1.0î x 1.0î scaled squares of t his file, 100í d plo 10,000sf 50í scale 5,000sf w. ja ckso n 50í 100’ 2,500sf 50í 1” = 36 Pedestrian pedestrianoriented design Human social dynamics balance private and common space Vehicular automobile accommodation late TOTAL society VALUE economy society VALUE ecology middle economy VALUE ecology early society concentrated clustered dispersed rectilinear (Concentrated, clustered and dispersed adapted from Weber 208) FORM DENSITY curvilinear Waste wastewater and foodscraps recycled onsite VALUE Triple Bottom Line = ecology, economy, society high priority = 5 low priority= 1 LAND USE Agriculture mutually supported organic farm, and potential CSA ecology Energy photovoltaics and wind energy Typical infrastructure site connections to supplemental, traditional infrastructure economy Dwelling sustainable housing Dwelling Agriculture Preserve Vehicular access CIRCULATION The client narrative (Page 35) was then added as a method of valuing design decisions by low or high priority, where 1 = low priority and 5 = high priority. The resultant client value per design decision and, in some instances, entire design alternative could then be evaluated for comparison to inform a design proposal. Drainage stormwater runoff is slowed, and/or captured for reuse Vehicular storage Pedestrian access Impermeable drainage Semipermeable drainage Permeable drainage UTILITY The design decision matrix (Bottom right) was developed to test a variety of land use aggregations with consideration for fundamental site amenities and social dynamics of residential development. This began by comparing form and density in conjunction with variables of land use, circulation, utilities, and social dynamics. Preserve protected prairie, woodland, and wetland SOCIAL DESIGN PROCESS Waste Energy Typical infrastructure Exposure Private open space Common open space 37 DESIGN PROCESS The photograph at right shows topography (Dashed line) and potential gateways (Dashed and solid circles) into the site in conjunction with local zoning and code restrictions (United States). This was the base layer for generating design alternatives that experimented within the framework of the design decision matrix. 38 DESIGN PROCESS_Alternative 1 VALUE Triple Bottom Line = ecology, economy, society high priority = 5 low priority= 1 middle late society ecology economy 3 4 5 3 5 4 3 3 5 35 Agriculture 5 5 5 1 3 1 4 5 5 34 Preserve 3 2 5 2 2 3 3 3 5 28 Vehicular access 1 2 1 1 3 3 1 2 1 15 Vehicular storage 1 2 3 1 3 1 1 2 3 17 Pedestrian access 1 2 1 1 4 3 1 2 1 16 Waste 5 5 1 1 5 1 5 5 1 29 Energy 5 5 5 3 5 3 5 5 4 40 TOTAL economy Dwelling society ecology VALUE society VALUE economy concentrated clustered dispersed rectilinear VALUE ecology CIRCULATION early Impermeable drainage Semipermeable drainage UTILITY Permeable drainage SOCIAL Alternative 1 above exhibited high priority for clustered dwellings and agriculture. The green and red highlighted squares of the diagram (Far right) indicate green for having equal to- or highest priority of all design alternatives, while indicate red for having equal to- or lowest priority of all design alternatives. LAND USE curvilinear FORM DENSITY Typical infrastructure Exposure 5 3 4 12 Private open space 4 4 4 12 Common open space 3 4 4 11 249 39 DESIGN PROCESS_Alternative 2 VALUE Triple Bottom Line = ecology, economy, society high priority = 5 low priority= 1 middle late society ecology economy 3 4 5 3 5 4 3 3 5 35 Agriculture 5 5 5 1 3 1 4 5 5 34 Preserve 5 2 5 2 2 3 4 3 5 31 Vehicular access 1 3 3 1 2 1 15 TOTAL economy Dwelling society ecology VALUE society VALUE economy VALUE ecology concentrated clustered dispersed rectilinear early 1 2 1 Vehicular storage 1 2 3 1 3 1 1 2 Pedestrian access 1 2 1 1 4 3 1 2 1 16 Waste 5 5 1 1 5 1 5 5 1 29 Energy 5 5 5 3 5 3 5 5 4 40 3 17 Impermeable drainage Semipermeable drainage UTILITY Permeable drainage SOCIAL Alternative 2 above exhibited high priority for clustered dwellings and agriculture. The green and red highlighted squares of the diagram (Far right) indicate green for having equal to- or highest priority of all design alternatives, while indicate red for having equal to- or lowest priority of all design alternatives. Notice low prioirty for dispersed vehicular access and storage. CIRCULATION LAND USE curvilinear FORM DENSITY Typical infrastructure Exposure 5 3 4 12 Private open space 4 4 4 12 Common open space 5 3 5 13 254 40 DESIGN PROCESS_Alternative 3 VALUE Triple Bottom Line = ecology, economy, society high priority = 5 low priority= 1 middle late society ecology economy 2 3 5 1 5 5 4 3 5 33 Agriculture 5 3 5 1 3 1 4 4 5 31 Preserve 4 1 5 2 2 3 4 3 5 29 Vehicular access 2 2 5 1 1 1 3 3 5 23 Vehicular storage 1 3 1 1 3 1 1 3 1 15 Pedestrian access 4 3 5 1 5 5 5 3 5 36 Waste 5 5 1 1 5 1 5 5 1 29 Energy 5 5 5 3 5 2 5 5 4 39 TOTAL economy Dwelling society ecology VALUE society VALUE ecology VALUE economy concentrated clustered dispersed rectilinear early Impermeable drainage Semipermeable drainage UTILITY Permeable drainage SOCIAL Alternative 3 above exhibited high priority for concentrated vehicular access. The green and red highlighted squares of the diagram (Far right) indicate green for having equal to- or highest priority of all design alternatives. Notice that this alternative also had one of the highest priorities of all the design alternatives, with a total of 275 (Bottom right diagram in green). CIRCULATION LAND USE curvilinear FORM DENSITY Typical infrastructure Exposure 5 2 5 12 Private open space 5 5 5 15 Common open space 5 3 5 13 275 41 DESIGN PROCESS_Alternative 4 VALUE Triple Bottom Line = ecology, economy, society high priority = 5 low priority= 1 middle late society ecology economy 3 4 1 1 5 4 3 3 4 28 Agriculture 1 3 4 1 3 1 3 4 4 24 Preserve 4 2 3 2 2 3 4 3 5 28 Vehicular access 3 2 1 1 1 3 3 2 1 17 Vehicular storage 1 1 1 1 3 1 1 2 1 12 Pedestrian access 4 3 3 1 4 1 3 3 4 26 Waste 5 5 1 1 5 1 5 5 1 29 Energy 5 5 3 3 5 3 5 5 4 37 TOTAL economy Dwelling society ecology VALUE society VALUE economy VALUE ecology concentrated clustered dispersed rectilinear early Impermeable drainage Semipermeable drainage UTILITY Permeable drainage SOCIAL Alternative 4 above exhibited low priority for concentrated dwellings and vehicular storage, and for clustered preserve. The red highlighted squares of the diagram (Far right) indicate red for having equal to- or lowest priority of all design alternatives. Notice that this alternative also had one of the lowest priorities of all the design alternatives, with a total of 232 (Bottom right diagram in red). CIRCULATION LAND USE curvilinear FORM DENSITY Typical infrastructure Exposure 3 1 3 7 Private open space 2 3 2 7 Common open space 5 3 5 13 232 42 DESIGN PROCESS_Alternative 5 VALUE Triple Bottom Line = ecology, economy, society high priority = 5 low priority= 1 middle late society ecology economy 3 4 2 2 5 4 3 3 4 30 Agriculture 2 3 2 1 3 1 3 4 3 22 Preserve 4 2 5 2 2 3 4 3 5 30 Vehicular access 3 2 1 1 3 3 3 2 1 19 Vehicular storage 1 2 1 1 3 1 1 2 5 17 Pedestrian access 4 3 5 1 5 5 5 3 5 36 Waste 5 5 1 1 5 1 5 5 1 29 Energy 5 5 3 3 5 3 5 5 4 40 TOTAL economy Dwelling society ecology VALUE society VALUE economy VALUE ecology concentrated clustered dispersed rectilinear early Impermeable drainage Semipermeable drainage UTILITY Permeable drainage SOCIAL Alternative 5 above exhibited low priority for clustered agriculture. The red highlighted square of the diagram (Far right) indicates red for having equal to- or lowest priority of all design alternatives. CIRCULATION LAND USE curvilinear FORM DENSITY Typical infrastructure Exposure 3 1 3 7 Private open space 2 3 2 7 Common open space 5 3 5 13 250 43 DESIGN PROCESS_Alternative 6 late TOTAL society VALUE economy society economy VALUE ecology middle ecology society VALUE economy concentrated clustered dispersed rectilinear early Dwelling 3 4 2 2 5 4 3 3 4 30 Agriculture 2 3 1 1 3 1 3 4 3 21 Preserve 4 2 5 2 2 3 4 3 5 30 Vehicular access 3 2 1 1 3 3 3 2 1 19 Vehicular storage 1 2 1 1 3 1 1 2 5 17 Pedestrian access 4 3 5 1 5 5 5 3 5 36 Waste 5 5 1 1 5 1 5 5 1 29 Energy 5 5 5 3 5 3 5 5 4 40 Impermeable drainage Semipermeable drainage UTILITY Permeable drainage SOCIAL Alternative 6 above exhibited low priority for concentrated agriculture. The red highlighted square of the diagram (Far right) indicates red for having equal to- or lowest priority of all design alternatives. CIRCULATION LAND USE curvilinear FORM DENSITY ecology VALUE Triple Bottom Line = ecology, economy, society high priority = 5 low priority= 1 Typical infrastructure Exposure 3 1 3 7 Private open space 2 3 2 7 Common open space 5 3 5 13 249 44 DESIGN PROCESS_Alternative 7 VALUE Triple Bottom Line = ecology, economy, society high priority = 5 low priority= 1 middle late society ecology economy 2 3 5 1 5 5 4 3 5 33 Agriculture 5 3 5 1 3 1 4 4 5 31 Preserve 4 1 5 2 2 3 4 3 5 29 Vehicular access 2 2 3 1 2 1 3 3 1 18 Vehicular storage 1 2 1 1 3 1 1 2 1 13 Pedestrian access 4 4 5 1 5 5 5 3 5 37 Waste 5 5 1 1 5 1 5 5 1 29 Energy 5 5 5 3 5 2 5 5 4 39 TOTAL economy Dwelling society ecology VALUE society VALUE economy VALUE ecology concentrated clustered dispersed rectilinear early Impermeable drainage Semipermeable drainage UTILITY Permeable drainage SOCIAL Alternative 7 above exhibited high priority for clustered pedestrian access. The green highlighted square of the diagram (Far right) indicates green for having equal to- or highest priority of all design alternatives. CIRCULATION LAND USE curvilinear FORM DENSITY Typical infrastructure Exposure 5 2 5 12 Private open space 5 5 5 15 Common open space 5 3 5 13 268 45 DESIGN PROCESS_Alternative 8 VALUE Triple Bottom Line = ecology, economy, society high priority = 5 low priority= 1 economy society ecology economy 2 3 5 1 5 5 4 3 5 33 Agriculture 5 3 5 1 3 1 4 4 5 31 Preserve 4 1 5 2 2 3 4 3 5 29 Vehicular access 2 2 3 1 3 1 3 3 1 19 Vehicular storage 1 2 1 1 3 1 1 2 1 13 Pedestrian access 4 3 5 1 5 5 5 3 5 36 Waste 5 5 1 1 5 1 5 5 1 29 Energy 5 5 5 3 5 2 5 5 4 39 TOTAL ecology Dwelling society society VALUE economy VALUE late ecology concentrated clustered dispersed rectilinear VALUE middle Impermeable drainage Semipermeable drainage UTILITY Permeable drainage SOCIAL Alternative 8 above exhibited relatively high priority, comparatively, with a total of 269 (Bottom right diagram). CIRCULATION LAND USE curvilinear FORM DENSITY early Typical infrastructure Exposure 5 2 5 12 Private open space 5 5 5 15 Common open space 5 3 5 13 269 46 DESIGN PROCESS_Alternative 9 VALUE Triple Bottom Line = ecology, economy, society high priority = 5 low priority= 1 economy society ecology economy 3 3 4 1 4 2 4 3 2 26 Agriculture 5 3 5 1 3 1 4 4 5 31 Preserve 4 1 5 2 2 3 4 3 5 29 Vehicular access 2 2 3 1 5 1 3 4 1 22 Vehicular storage 1 3 5 1 3 1 1 2 5 22 Pedestrian access 1 3 5 1 5 5 5 3 5 33 Waste 5 5 1 1 5 1 5 5 1 29 Energy 5 5 5 3 5 2 5 5 4 39 TOTAL ecology Dwelling society society VALUE economy VALUE late ecology concentrated clustered dispersed rectilinear VALUE middle Impermeable drainage Semipermeable drainage UTILITY Permeable drainage SOCIAL Alternative 9 above exhibited high priority for dispersed vehicular storage. The green highlighted square of the diagram (Far right) indicates green for having equal to- or highest priority of all design alternatives. CIRCULATION LAND USE curvilinear FORM DENSITY early Typical infrastructure 9 Exposure 5 2 2 Private open space 5 5 5 15 Common open space 5 3 5 13 268 47 DESIGN PROCESS_Composite Alternative In this respect, the highest priority alternatives were also congruent with curvilinear circulation. This seemed to CONTINUED NEXT PAGE society ecology economy 4 5 3 5 4 3 3 5 35 Agriculture 5 5 5 1 3 1 4 5 5 34 Preserve 4 1 5 2 2 3 4 3 5 29 Vehicular access 2 2 5 1 5 1 3 3 5 23 society economy 3 rigid ecology VALUE society VALUE late economy VALUE middle ecology concentrated clustered early Dwelling oblique LAND USE CIRCULATION dispersed FORM DENSITY 5 22 Vehicular storage 1 3 5 1 3 1 1 2 Pedestrian access 4 4 5 1 5 5 5 3 5 37 Waste 5 5 1 1 5 1 5 5 1 29 Energy 5 5 5 3 5 2 5 5 4 39 Impermeable drainage Semipermeable drainage Permeable drainage UTILITY The design alternatives revealed highest priority for clustered dwellings with dispersed vehicular storage. This seemed validated by the idea that community user groups would not want to travel a great distance from their domicile to their automobile. It also seemed justified by a balanced sense of community life that clustered dwelling aggregations can provide, instilling feelings of safety and privacy. VALUE Triple Bottom Line = ecology, economy, society high priority = 5 low priority= 1 SOCIAL The diagram at right is a composite of high priority design decisions as assesed through the previously outlined design alternatives. Typical infrastructure 9 Exposure 5 2 2 Private open space 5 5 5 15 Common open space 5 3 5 13 285 48 DESIGN PROCESS_Composite Alternative stem from desirable exposure and viewsheds created by the variation of a curvilinear form, and proved advantageous for low-impact development since the curvilinear form paralleled existing site topography. Agricultural activity that was clustered adjacent to aforesaid dwelling clusters, likewise, revealed high priority. This, again, seemed to stem from the ease of accessibility and potential for private intensive horticultural plots that would result. ished accessibility to vehicular storage and day-to-day agricultural operations, and from more exposure with less privacy. The results were compiled into a composite design decision matrix (Previous page), and translated into a working design proposal that will be outlined in the next section. Excluding the ecological benefits and high priority of a ‘concentrated’ preserve space, low priority generally surrounded concentrated design distributions. This was on account of dimin49 DESIGN PROPOSAL In this section the composite design decision matrix from the end of the previous section is evolved into a design proposal. Housing clusters are established at a variety of scales and capacities to include private intensive horticultural plots, verstatile accessibility, and promote diversity of community user groups. Two form-based diagrams were developed to organize housing into two primary types: detached housing and row housing. Diagram development was facilitated through a spreadsheet of spatial relationships. Combined, the spreadsheets and corresponding diagram act as performance specifications for the eventual architectural design interventions of site structures, and codify a framework for community layout. They also ensure the temporal success of site systems and operations through schematic programming. The spatial relationships diagrams correlate with three scales of residential property aggregations deployed onto the proposed site. Three scales were adopted to promote diverse user groups and encourage community growth. Schematic programming of shared community park space and orchards throughout the proposed layout plan also ensure active buffer space to be shaped by the community. DESIGN PROPOSAL_Spatial Relationships Key ABBREVIATION ag. cell dwelling pr. op. space agriculture ped. access agricultural cell represents a barn, shed, agricultural storage and/or staging area dwelling is the enclosed human domicile private open space is a semioutdoor room, and/or enclosure agriculture is a privately owned, intensive horticulture plot that must be in use pedestrian access indicates proposed pedestrian circulation veh. storage vehicular storage indicates proposed parking for autmobiles veh. access vehicular access indicates proposed vehicular circulation property line shared access DEFINITION property line delineates private ownership of residential plots shared access permeable paving for both pedestrians and vehicles (Diagram adapted from Weber 208) 51 DESIGN PROPOSAL_Spatial Relationships Spreadsheet OVERLAP (Adapted from Weber 208) intersection adjacency connection intersection “Condition where activities spill into each other sharing mututal areas across an ill-defined boundary.” (Weber 208) adjacency “Clear definition of contiguous realms sharing only a common boundary.” (208) connection “Linkage of two territories across a third mediating realm.” (208) Refer to spatial relationships key (Previous page) to reference items in the relationships below dwelling ped. access dwelling veh. storage dwelling ped. access veh. storage veh. access dwelling ped. access veh. access dwelling veh. access pr. op. space veh. storage dwelling veh. access preserve ag. cell dwelling pr. op. space agriculture ped. access dwelling pr. op. space ped. access Two columns were included to accommodate multiple conditions when present ag. cell dwelling ag. cell veh. access pr. op. space ag. access 52 DESIGN PROPOSAL_Spatial Relationships Spreadsheet Row Housing OVERLAP (Adapted from Weber 208) intersection adjacency connection Refer to spatial relationships key to reference specific items of relationships below dwelling ped. access dwelling veh. storage dwelling ped. access veh. storage veh. access dwelling ped. access veh. access ag. cell dwelling veh. access pr. op. space veh. storage dwelling veh. access preserve ag. cell dwelling pr. op. space agriculture ped. access dwelling pr. op. space ped. access dwelling ag. cell veh. access pr. op. space ag. access 53 DESIGN PROPOSAL_Spatial Relationships Diagram Row Housing dwelling 10’ SETBACK pr. op. space agriculture 10’ SETBACK ag. cell ped. access veh. storage 10’ SETBACK veh. access property line shared access 54 DESIGN PROPOSAL_Spatial Relationships Spreadsheet Detached Housing OVERLAP (Adapted from Weber 208) intersection adjacency connection Refer to spatial relationships key to reference specific items of relationships below dwelling ped. access dwelling veh. storage dwelling ped. access veh. storage veh. access dwelling ped. access veh. access ag. cell dwelling veh. access pr. op. space veh. storage dwelling veh. access preserve ag. cell dwelling pr. op. space agriculture ped. access dwelling pr. op. space ped. access dwelling ag. cell veh. access pr. op. space ag. access 55 DESIGN PROPOSAL_Spatial Relationships Diagram Detached Housing ag. cell dwelling 5’ SETBACK b/w PL pr. op. space agriculture ped. access 10’ SETBACK veh. storage veh. access property line shared access 56 DESIGN PROPOSAL_Layout Plan community orchard edible orchard shared by community residents intensive horticulture plots privately owned allotment gardens, always in use during growing season, can be leased row-housing agricultural cell shared barn for storage and cluster staging area residential area for dwelling and private open space where applicable preserve protected native prairie and wetland park park space shared by community residents for varied uses vehicular/pedestrian access high fly-ash concrete primarily for automobiles permeable pavement accommodates vehicular and pedestrian circulation for agricultural operations pedestrian access recreational circulation for residents and visitors 57 DESIGN PROPOSAL_Detached Housing Deployment 10’ SETBACK 5’ SETBACK b/w PL (Please refer to page 48 for detailed spatial relationships key) Property total = 47 lots @ 110’ x 50’ Residential space dwelling/open space = 3,000 sf @ 60’ x 50’ total = 141,000sf (3.23ac) Allotment garden plot = 2,500 s.f @ 50’ x 50’ total = 117,500 sf (2.70ac) 58 DESIGN PROPOSAL_Row Housing Deployment_Type 1 10’ SETBACK 10’ SETBACK 10’ SETBACK (Please refer to page 48 for detailed spatial relationships key) Property total = 32 lots @ 110’ x 30’ Residential space dwelling/open space = 2,100sf @ 70’ x 30’ total = 67,200sf (1.54ac) Allotment garden plot = 1,200 s.f @ 40’ x 30’ total = 38,400 sf (.88ac) 59 DESIGN PROPOSAL_Row Housing Deployment_Type 2 10’ SETBACK 10’ SETBACK 10’ SETBACK (Please refer to page 48 for detailed spatial relationships key) Property total = 38 lots @ 90’ x 25’ Residential space dwelling/open space = 1,250sf @ 50’ x 25’ total = 47,500sf (1.09ac) Allotment garden plot = 1,000 s.f @ 40’ x 25’ total = 38,000 sf (.87ac) 60 DESIGN PROPOSAL_Layout Plan_Results private property land use ≈23% (10.31ac) allotment gardens total = 4.45ac 5’ contours orchards supported by homeowners’ association parks maintained by homeowners’ association residential space total = 5.86ac barns qty = 5 dim = 3,200sf/barn total = 160,000sf KEY primary vistas across preserve, secondary vistas along orange perimeter .5-mile recreational circuit created with pedestrian oriented streetscapes proposed for w. jackson and n. morrison roads potential staging area for bus stop, picnic tables, benches, vendors prese rve shared community space land use ≈77 (31.50ac) high fly-ash concrete has 30’ orchards inside turning radius total = 7.80ac to accommodate all emergency vehicles parks total = 2.50ac active park space preserve provides staging total = 841,910sf area for social (19.33ac) events for families and the community, circulation also playground total ≈1.5ac equipment permeable pavement has 15’ inside turning radius to accommodate most vehicles dr a i na ge natural topography efficiently directs runoff to southeast corner of site, and runoff is cleansed at mychorrizal level by vegetative root zone and soil profile before entering watershed 61 DESIGN PROPOSAL_Layout Plan_Results Red filter private space ≈23% (10.31ac) VS. Blue filter common space ≈77% (31.50ac) This diagram was generated to better communicate the breakdown of private space versus common space. Private space was dictated by private ownership, where common space was dicated by communal ownership. 62 DESIGN PROPOSAL n. morrison w. ja ckso n 63 CONCLUSION A design methodology for sustainable community development was the outcome of this creative project. Developing a detailed client narrative that attempted to reflect a human life effectively simulated the clientele of a proposed sustainable community. Embedding the triple bottom line of sustainability as a value system—ecology, economy, and society—established client priority indicators for justifying design decisions. This yielded a co-authorship of designer and client, which is a desirable real-world dynamic. The methodology generated by this creative project could be easily amended and/or applied to other proposed communities. “Amended,” since contextual research ultimately informed the land use capacities that the design decision matrix was able to evolve through design alternatives and final proposal. “Applied,” since the hypothetical client narrative would become an actual client with existing values to prioritize design decisions. The next step with the design proposal of this project would be the implementation of contextually-informed systems into its programmed spaces. For example, the preserve is loosely defined as a native prairie and wetland, and elaborating on the definition could become another project in itself—the soil profile, vegetation, topography, habitat, etc.—these could become design decisions within the design decision matrix that shape alternatives for prioritization and final design solution(s) of what the preserve could actually be. Perhaps there becomes a lake for people to swim, perhaps there is an ornithological sanctuary, perhaps the preserve is a mosaic representation of Indiana CONCLUSION_Continued wetlands? The opportunities are endless at a glance. Likewise, the agricultural operations could be explored regarding human diet, vegetation and environmental suitability, maintenance, etc. to become the most suitable agricultural operation(s) for a proposed, midwestern agrarian-based community in the twenty-first century. also reveals the role of the landscape architect as a multidisciplinary conductor and project manager, since programmed spaces are essentially ‘zoned’ by the layout plan for their intended purpose, but can also be designed to fulfill that purpose by allied professionals, or by the evolving role of the landscape architect as well. In this capacity, the creative project is not necessarily a finished deliverable, but a methodology for justifying sustainable community development, with the notion that finished and detailed layout plans could eventually be achieved. The project The spatial relationships diagram used for dwelling aggregations, in this regard, exercised the control a landscape architect can have in defining community character and establishing desirable social dynamics for the temporal success of all proposed systems—again, the ecological, economic, and social systems of the triple bottom line of sustainability. The biggest fault of this creative project was that the primary vehicular corridor defined the entire final form. This is contrary to the sustainable paradigm shift, and failed in many ways. For example, vehicular circulation could sever the protected preserve space from the inhabitants that seek its benefits, or more importantly, really not mitigate fossil fuel dependence at all by still embracing the automobile. 65 CONCLUSION_Continued Inhabitants are completely accommodated by the automobile, so much that clustered dwelling aggregations almost appear as metaphorical leaches of the primary vehicular vessel. The dwellings, preserve space, pedestrian circulation, and agricultural operations are all attached to- and dictated by the intervention of the primary vehicular corridor. This equates to automobileoriented design instead of pedestrian-oriented design, and not reflective of the sustainable paradigm shift. In retrospect, this could have manifested more desirable outcomes if design deci- sions had completely neglected the automobile in every capacity until later on in the design process. On the other hand, the existing layout of Muncie, Indiana is completely automobile dependent. The city has, for all intents and purposes, been built to service the automobile with virtually zero concessions made for the pedestrian (Excluding the instances of Ball State University’s campus and downtown). In this regard, the creative project would appear a significant community improvement in that it provided opportunities for recreation, manda- tory food production, and a protected preserve space for stormwater recharge and biodiversity that would be highly contrary to its context. If surrounding, heavily trafficked streetscapes have no sidewalks or recreational opportunities, the proposed site can only address sustainability at the site level, or by linking to existing public transportation (As proposed on page 11). Furthermore, since the automobile is accommodated the likelihood seems much higher for the local and regional popoulation to want to settle in the proposed community, and choose to 66 CONCLUSION_Continued relocate there. While forcing the automobile to the periphery or removing it entirely may have better validated the scope of sustainability, it could also be argued that such a community would not be embraced by its context and contemporary society for many years to come. conventional development at the community level. This creative project established a design methodology and tools for doing so. People will always need a place to call home—a dwelling, domicile, abode, house, quarters, address, residence—a safe place to sleep, eat, and live. Given the finite resources of Earth, and since the global population will inevitably continue to exponentially grow, it is important to begin reorienting 67 BIBLIOGRAPHY Allen, Jennifer, and Liesbeth Melis. Parasite Paradise: A Manifesto for Temporary Architecture and Flexible Urbanism. Rotterdam: NAi, 2003. Benya Lighting Design. 27 Feb. 2010. <http://www.benyalighting.com/>. Bussiere, Simon. E-GATE Public Realm. PDF Report. AECOM. Cal-Earth–The California Institute of Earth Art and Architecture. 05 Feb. 2010. <http:www.calearth.org>. Calkins, Meg. Materials for Sustainable Sites: a Complete Guide to the Evaluation, Selection, and Use of Sustainable Construction Materials. Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley, 2009. Center for Maximum Potential Building Systems—Building a Sustainable World Since 1975. 07 Feb. 2010. <http://www.cmpbs.org>. Condon, Patrick M. Sustainable Urban Landscapes: the Surrey Design Charrette. Vancouver, B.C.: University of British Columbia, James Taylor Chair in Landscape and Liveable Environments, 1996. Design like You Give a Damn: Architectural Responses to Humanitarian Crises. New York, NY: Metropolis, 2006. ECO-NOMIC homepage. 27 Feb. 2010. <http://www.eco-nomic.com>. Elizabeth, Lynne, and Cassandra Adams. Alternative Construction: Contemporary Natural Building Methods. New York, N.Y.: J. Wiley and Sons, 2000. Farr, Douglas. Sustainable Urbanism: Urban Design with Nature. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, 2008. Hunter, Kaki, and Donald Kiffmeyer. Earthbag Building: the Tools, Tricks and Techniques. Gabriola Island, BC: New Society, 2004. Idaho Forest Products Commission. 27 Feb. 2010. <http://www.idahoforests.org/>. Johnson, Bart, and Kristina Hill. Ecology and Design: Frameworks for Learning. Washington, DC: Island, 2002. Kronenburg, Robert. Portable Architecture. Oxford: Elsevier/Architectural, 2003. Madigan, Carleen. The Backyard Homestead. North Adams, MA: Storey Pub., 2009. McCamant, Kathryn, and Charles Durrett. Cohousing: a Contemporary Approach to Housing Ourselves. Berkeley, CA: Habitat, 1988. Michigan State University Student Organic Farm. Web. 10 Feb. 2011. <http://www.msuorganicfarm.org/>. Muncie Indiana Transit System. 10 Nov. 2010. <http://www.mitsbus.org/>. 69 Murphy, Diana, Cameron Sinclair, and Kate Stohr. Design like You Give a Damn: Architectural Responses to Humanitarian Crises. New York, NY: Metropolis , D.A.P., 2006. Peña, William, William Wayne Caudill, and John Focke. Problem Seeking: an Architectural Programming Primer. Boston: Cahners International, 1977. Powell, Bonnie Azab. “In Britain, Gardening Your ‘Allotment’ Is a Rite and Right, Washingtonpost.com.” The Washington Post: National, World & D.C. Area News and Headlines, Washingtonpost.com. Web. 14 Mar. 2011. <http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/05/12/ AR2009051201455.html>. Rael, Ronald. Earth Architecture. New York, N.Y.: Princeton Architectural, 2009. Romanos, Michael C. Residential Spatial Structure. Lexington, MA: Lexington, 1976. Ruano, Miguel. Eco Urbanism: Sustainable Human Settlements, 60 Case Studies = Eco Urbanismo Entornos Humanos Sostenibles, 60 Proyectos. Barcelona: Gustavo Gili, 1999. Scoates, Christopher. LOT-EK: Mobile Dwelling Unit. New York: D.A.P./Distributed Art, 2003. Serenbe Community. Serenbe Community - A 900-acre Sustainable Living Community in Palmetto Georgia. Web. 7 Mar. 2011. <http://www.serenbecommunity.com/home.html>. 70 Siegal, Jennifer. More Mobile Portable Architecture for Today. New York: Princeton Architectural, 2008. Site Selection Guidelines and Performance Benchmarks 2009. Sustainable Sites Initiative. 5 Feb. 2010. <http://www.sustainablesites.org>. Tryon Farm :: A Unique Conservation Community. 10 Feb. 2011. <http://www.tryonfarm.com/>. United States. Delaware-Muncie Metropolitan Plan Commission. City of Muncie Comprehensive Zoning Ordinance. United States. Delaware-Muncie Metropolitan Plan Commission. Delaware County Comprehensive Zoning Ordinance. Weber, Hanno. The Evolution of a Place to Dwell. DRS Journal: Design Research and Methods Jul-Sep 7.3 (1973): 207-12. All satellite imagery, unless otherwise indicated, was accessed and/or modified from Google Earth between January 2010 and March 2011. 71