Incentives for Biodiversity Conservation: An Ecological and Economic Assessment

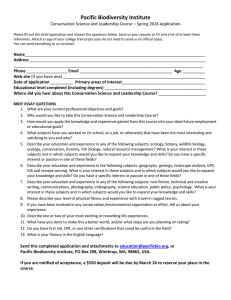

advertisement