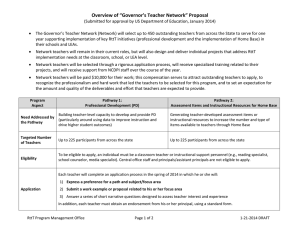

(138 total points Section D - Overview North Carolina RttT Proposal

advertisement