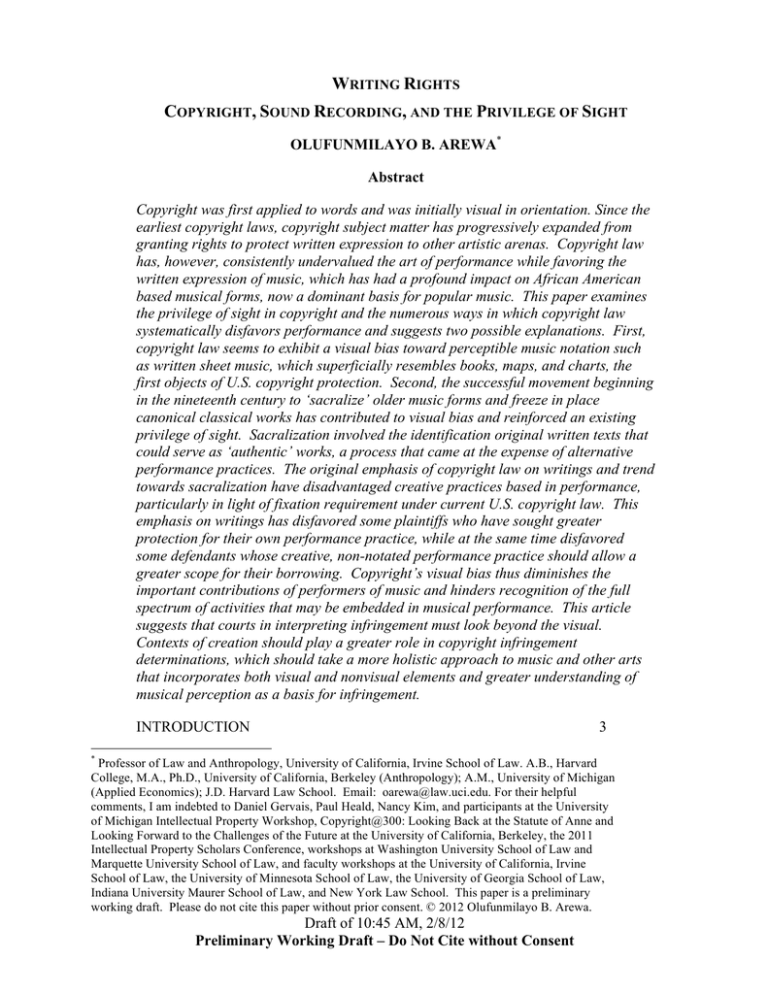

W R C

advertisement