P C A

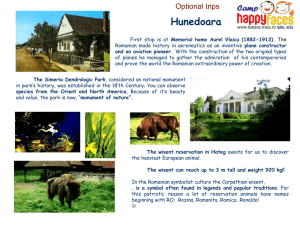

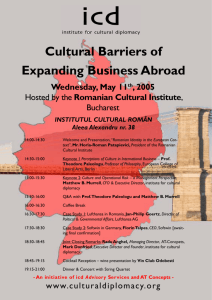

advertisement