IMPACT OF AN INFANT SIMULATION PROGRAM ON PREVENTION OF ADOLESCENT PREGNANCY

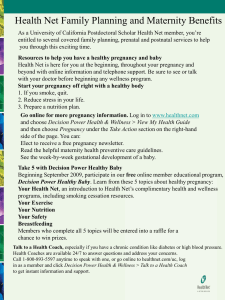

advertisement