CHARLOTTE: SETTING THE STANDARD FOR RAIL TRANSIT IN MID-SIZED CITIES

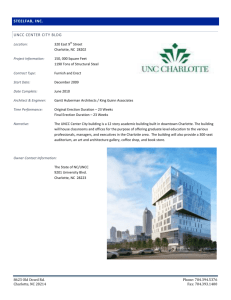

advertisement