Document 10900935

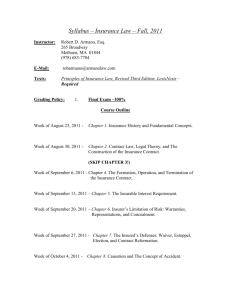

advertisement