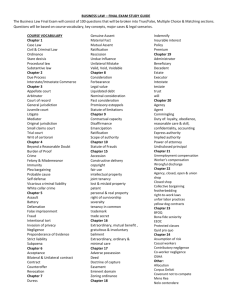

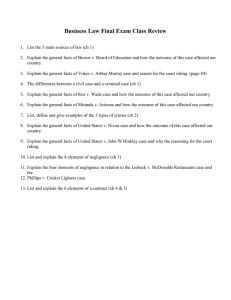

S M ,

advertisement