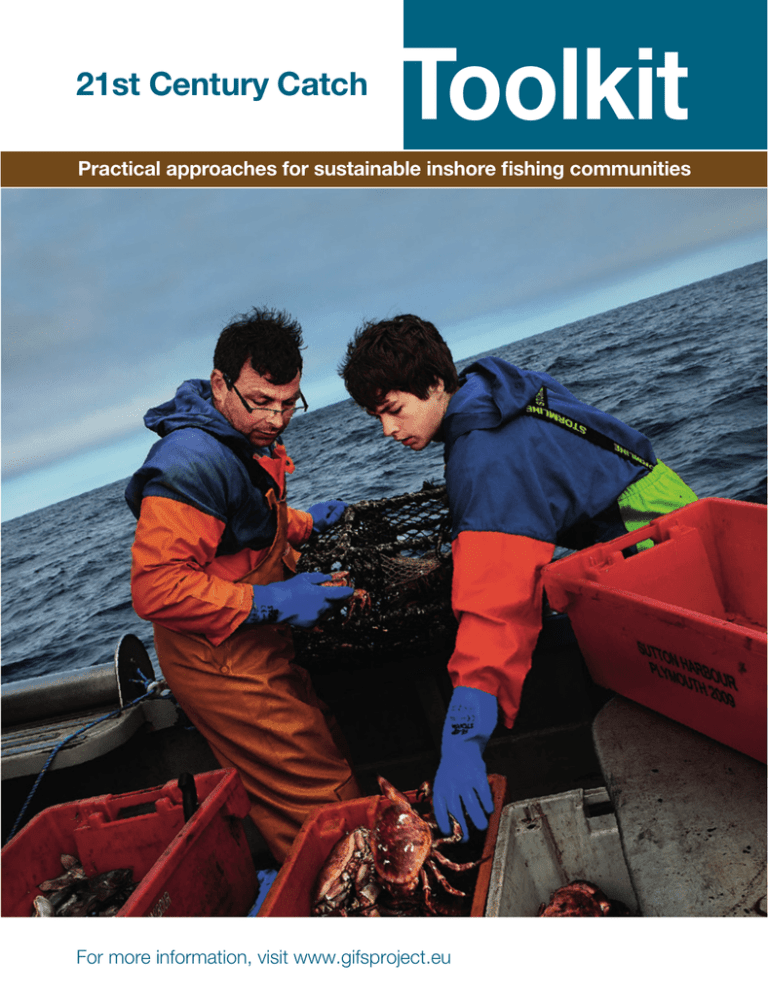

Toolkit 21st Century Catch Practical approaches for sustainable inshore fishing communities

advertisement