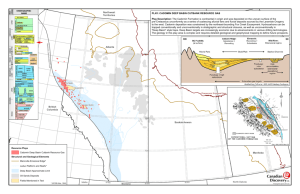

Petroleum geology of Pennsylvanian and Lower Permian strata, Tucumcari Basin,

advertisement