ARTICLE CRUISE CONTROL AND SPEED BUMPS: ENERGY POLICY AND LIMITS FOR OUTER

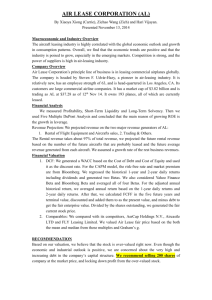

advertisement