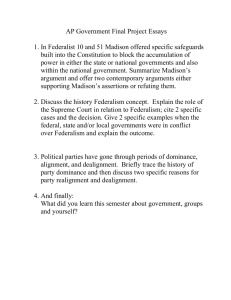

Article

advertisement