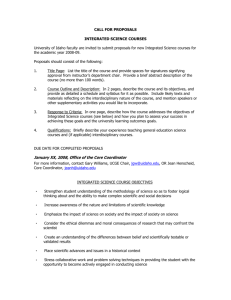

ARTICLE RULES AND STANDARDS IN COPYRIGHT

advertisement