Document 10868958

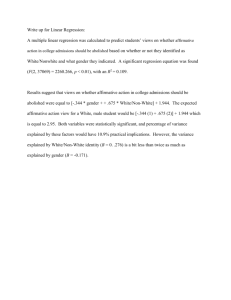

advertisement