Document 10868910

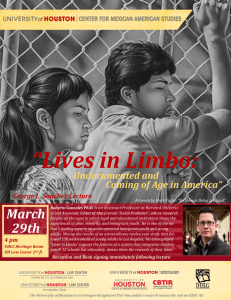

advertisement