Document 10868899

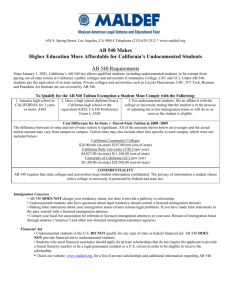

advertisement