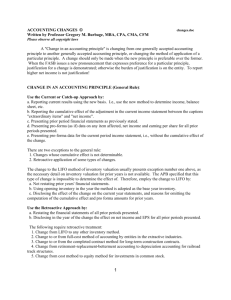

Court: Insurers Must Be Even Clearer In Explaining Retroactive Dates... Medical Malpractice Policies

advertisement

Court: Insurers Must Be Even Clearer In Explaining Retroactive Dates In Group Medical Malpractice Policies Seth J. Chandler schandler@uh.edu August 29, 2004 Many physicians currently have protection from lawsuits under what are called “claims made” liability insurance policies. These policies, unlike “occurrence” based policies, protect the insured only against “claims” made during the period of the policy or a usually brief extended reporting/discovery period thereafter. Thus, a doctor who obtains a pure claims made policy for some period of time and who fails to obtain supplemental “tail coverage” through another claims made policy or another insurance instrument may find herself unprotected when, as frequently occurs, she allegedly commits malpractice during the policy period, but is not sued about it until quite some time afterwards. In addition, many claims made policies do not cover the insured for all claims made even during the effective period of the policy, but only those in which the underlying occurrence took place after a “retroactive date.” The absence of “tail coverage” coupled with retroactive dates narrows the scope of coverage under many claims made policies – a fact that has long troubled some courts. The recently decided case of President v. Jenkins, 180 N.J. 550, 853 A.2d 247 (2004), is yet another unleashing of judicial creativity in the efforts to reform claims made policy. The case likely forces insurers in New Jersey and elsewhere to reform their policy forms and sales practices to physicians in ways that hammer home, even more forcibly than before, the limitations of claims made policies. It has particular relevance to the frequent occasions on which physicians purchase medical malpractice insurance through membership in a “group” that serves primarily as a conduit for such sales. The case is a striking example of the willingness of some courts to reshape liability insurance policies in order to maximize the potential for compensation to victims of medical malpractice. The facts of President are stunning because they would appear to the untrained eye to be one of the strongest possible cases for not reshaping an insurance policy. An obstetrician insured (Jenkins) let his prior occurrence based liability insurance policy lapse in October 1997 because of his failure to pay premiums. On January 8, 1998, having been previously notified of the developing problems with his earlier occurrence policy, and a few days after allegedly committing medical malpractice against the President family by failing to diagnose eclampsia1, he sought out new liability insurance coverage. He did so by approaching an insurance agency that worked with the Garden State Physician’s Alliance (“the physician group”), which in turn had a group policy with Zurich Insurance Company, a large insurer. Zurich did not issue medical malpractice insurance directly to physicians but rather added physicians as additional insureds to its master policy for calendar year 1999 with the physician group. The obstetrician filled out an application in which he (a) said that his professional liability insurance had never been “denied, cancelled, or not renewed2”; and (b) signed his name right under the following 1 The failure to diagnose allegedly resulted in a baby with brain damage, partial paralysis and a seizure disorder. 2 Although this statement may not technically have been a lie in that the formal letter from the occurrence insurer canceling retroactive to October 26, 1997, did not arrive until the next day, January 9, 1998, there is no evidence in the President opinion that the insured ever corrected what, after January 9, statement “I understand that the coverage offered is provided by a claims-made policy and that incidents that occurred prior to the prior acts or retroactive date are not covered and claims reported after the expiration date are not covered unless I purchase or otherwise obtain an extended reporting endorsement by Zurich.” (emphasis by court). Subsequent events reinforced on Dr. Jenkins the importance of the retroactive date. To finance the premiums for the new policy, Dr. Jenkins filled out forms that confirmed that the effective date of the new policy would be February 1, 1998. Dr. Jenkins promptly received temporary insurance (via a “binder”) that identified February 1, 1998, to April 1, 1998, as the binder period and February 1, 1998, as the “retroactive date.” Dr. Jenkins received a certificate of insurance that set February 1, 1998, as the effective date and January 1, 1999, as the expiration date. And Dr. Jenkins received an endorsement to the master policy that listed him as an additional insured and that specified a retroactive date of February 1, 1998. The master policy (accurately) set forth its own effective date as January 1, 1998. Finally, in April 1998, Dr. Jenkins received a copy of the full policy which stated on its cover page, “We will pay on behalf of a physician, damages that the physician shall become legally obligated to pay because of a claim first made during the policy period arising out of a medical incident which 1998, appears to have been a material false statement. See Stipich v. Metropolitan Life Ins. Co., 277 U.S. 311, 317 (1928) (“If, while the company deliberates, [the insured] discovers facts which make portions of his application no longer true, the most elementary spirit of fair dealing would seem to require him to make a full disclosure.”). The New Jersey Supreme Court case makes no reference to any claim of fraud or misrepresentation made by the insurer against the insured, though this may simply be because the issues were not addressed in the summary judgment under review. occurred on or after the retroactive date and which is reported to us during the policy period.” (emphasis by court). The victims of the malpractice brought suit in September 1999, and Dr. Jenkins sought protection as an additional insured under the Zurich policy. Dr. Jenkins also sued the insurance agency on the alternative theory that, if there were no coverage, it was the result of the agent’s failure to procure it on his behalf. Citing the retroactive date provision, Zurich sought summary judgment. And arguing that the insured had (falsely) told them that his old coverage expired on February 1, 1998, thus obviating the need for any pre-existing coverage, the insurance agency sought summary judgment too. The trial court granted both motions for summary judgment and the intermediate appellate court affirmed, over a dissent. On appeal, the New Jersey Supreme Court upheld summary judgment in favor of the insurance agency but reversed and remanded with respect to the claim against Zurich. The court found the insurance policy “ambiguous” and potentially contrary to the insured’s “reasonable expectations.” The court’s finding of ambiguity rested primarily on its description of a conflict between the retroactive date of the master policy for claims against the physician group itself and the retroactive date applicable to claims against physicians added as additional insureds. Cf. Rusthoven v. Commercial Standard Insurance Co., 387 N.W.2d 642 (Minn. 1986) (noting that ambiguity can be created by two crystal clear provisions in a policy, each of which contradicts the other). The former was January 1, 1997, while the latter depended on when a particular physician was added to the policy.3 The court also noted that the binder was ambiguous “because the retroactive date was set after the policy’s effective date; thus it provided no retroactive coverage at all.”4 As a prelude to these findings, the court discussed with enthusiasm its earlier holding in the controversial case of Sparks v. St. Paul Ins. Co., 100 N.J. 325, 495 A.2d 406 (1985). There, it had criticized claims made policies with minimal retroactive periods as not offering an adequate “quid pro quo” for the limitations placed on “tail claims” created by claims made policies.5 3 There is no evidence that Dr. Jenkins ever read the policy’s provisions regarding the group retroactive date (or anything else). The case is thus typical of many in insurance law in which the ambiguity said to justify the court in reshaping the policy is discovered only by lawyers after the fact. Ambiguity doctrine thus may be thought of in part as a doctrine that prophylactically improves insurance policy clarity (a) for the few individuals brave enough to read them ahead of a dispute and (b) for courts who have to struggle with them afterwards. 4 How this lack of coverage makes the policy “ambiguous” is unclear. It may make the policy “unfair”, it may even render the policy contrary to the reasonable expectations of the insured, but hitherto the issue of oppression has generally been thought distinct from the issue of ambiguity. See Celestino v. Mid-American Indemnity Co., 883 S.W.2d 310 (1994) (policy that covers absolutely nothing is not ambiguous, but it may well be unconscionable). 5 The case is controversial not only because of its evident hostility towards widely used claims made policies but also because the alleged flaw with the policy – a retroactive date that coincided with the inception of the policy – actually had no factual relationship to the failure of the insurer to pay. As the court realized, 495 A.2d 416 n.5, even if the policy had been retroactive back to the beginning of time, there would have been no coverage under the policy: the insurer didn’t pay because the policy lapsed (for nonpayment of premiums) before the claim was ever made. So offensive was an irrelevant provision of the Having found ambiguity, the court then reversed summary judgment by holding that the insured had presented adequate evidence that his “reasonable expectation” was that the policy did not contain the sort of limiting retroactive date actually contained in the language of the policy.6 The President opinion could be analyzed in a conventional fashion. It may also be read, however, merely as a symptom of judicial discomfort with a medical system in which acquisition of medical malpractice insurance is optional. Thus, the compensation received by patients that suffer devastating injuries can rest on the often inadequate assets of their medical injurer. This latter reading is inspired by the willingness of the court to embrace a result favoring coverage here without careful consideration of contrary arguments about the proper functioning of a private and optional insurance market. The hostility towards retroactive dates continued from the earlier Sparks decision ignores, for example, the utility of such provisions in preventing the sort of market-destroying adverse selection that plagues private, optional insurance markets. Without such provisions, physicians who know they have potential claims against them can simply contract, however, that the court refused to honor a presumably inoffensive and crystal clear relevant provision of the contract. Insertion of a short retroactive period was thus treated more like a tort. 6 In a separate segment of the opinion, the court found that the insurance agent could not be liable because the agent believed – based on the insured’s representations – that “any additional retroactive coverage (any coverage prior to February 1, 1998) would have been superfluous. The New Jersey court thus appears to be holding either that an insured can have a reasonable expectation of superfluous coverage or that this insured is not estopped from asserting any reasonable expectation of coverage by virtue of having made false representations about the need therefore to his insurance agent. stock up on claims made policies once they suspect such a claim to be imminent. To be sure, such adverse selection can theoretically be prevented by expensive investigatory underwriting or reliance on the law of fraud and misrepresentation, but the standards erected by courts to prove fraud and misrepresentation are often sufficiently high as to make exclusive reliance on that body of law somewhat impractical. The court now adds to its hostility towards claims made policies, a new hostility towards group policies. Such policies are widely used in medical malpractice and other fields in part because of their ability to reduce transaction and marketing costs. Of course there are multiple retroactive dates in a group liability insurance policy. The whole point is that the group is continuous while additional insureds come and go. The insurer cannot shorten retroactive periods for the group every time a new physician joins the group. And it cannot extend retroactive periods for each physician back to the beginning of the group without risking severe adverse selection problems. How an insured could have a “reasonable expectation” to the contrary is something not explained by the President court. And, while conceivably the insurer could have made this point clearer to this insured through additional use of bold type or yet more definitions, it is doubtful that these complexities would actually have enlightened many insureds. Bolding every limitation in an insurance policy accomplishes little. But cf. Ponder v. Blue Cross of Southern California, 145 Cal. App. 3d 709, 193 Cal. Rptr. 632 (1983) (wanting health insurer to place all provisions limiting coverage in conspicuous type and to define fully in the contract itself “temporomandibular joint syndrome”). Thus, while the court’s hostility is literally confined to the failure of the insurer adequately to clarify its multiple retroactive dates, the difficulty of accomplishing that task with greater precision than already was done, impels speculation as to whether the hostility is actually directed toward the inevitable complexity of master contracts themselves. In the end, however, no matter how much some academic theorists may criticize New Jersey jurisprudence in this area, it remains the law for New Jersey and a potential precedent for other jurisdictions confronting similar issues.7 If they are to forego discontinuing group medical malpractice policies that often advantage insurers and physicians alike, medical malpractice insurers are now going to have to undertake painstaking steps to ensure that future insureds cannot claim “ambiguity” in avoiding retroactive dates. The result will at first likely be longer contracts and a more complex contracting process that few physicians will enjoy. The next case, therefore, is likely to be a direct confrontation between an insurance industry that seems set on widespread use of claims made policies with retroactive dates and segments of a judiciary hostile to the limited coverage such policies provide. 7 Other courts may, of course, refuse to follow President v. Jenkins as a “distinct minority view,” just as they have refused to follow the Sparks case.