NUCLEAR TERRORISM RESPONSE PLANS Major Cities Could

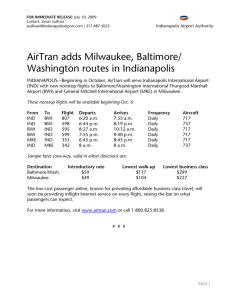

advertisement