- .#=-2330 .6 4/9)

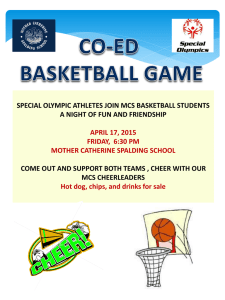

advertisement