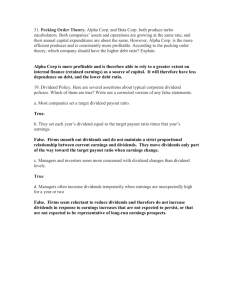

JUL 1401 LIBR AOR

advertisement