KNOWLEDGE INTEGRATION IN LARGE-SCALE ORGANIZATIONS AND

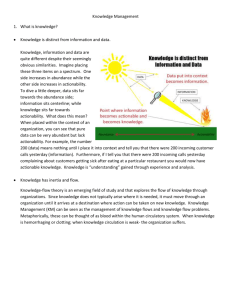

advertisement