Un nited Te echno logies

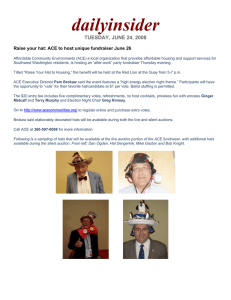

advertisement