Iterative Design and Natural Language

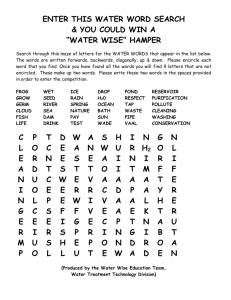

advertisement