Implications for the Australian Economy of Strong Growth in Asia Research

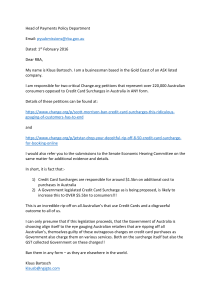

advertisement