O From the Chair ASSOCIATION’S COMMITTEE ON ANIMALS AND THE LAW

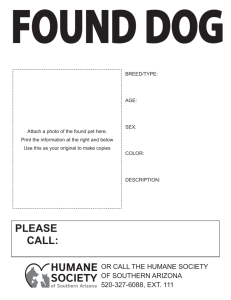

advertisement