(1940)

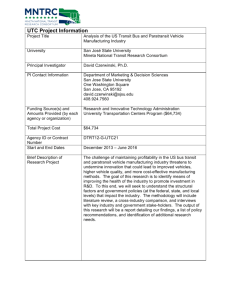

advertisement