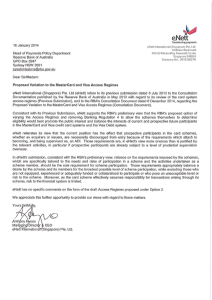

Payments system regulation and reform in interchange fee and surcharging policy

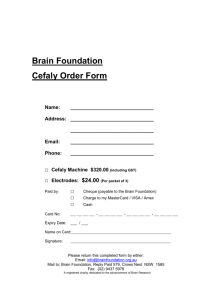

advertisement