City Growth and Community-Owned Land in Mexico City By

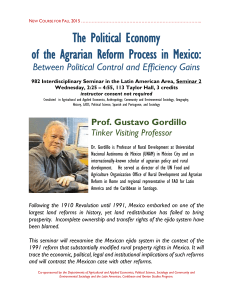

advertisement