AND SPACE A Eric Brende

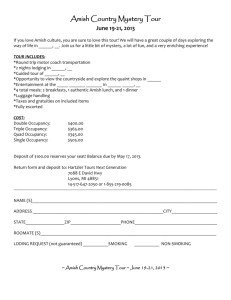

advertisement