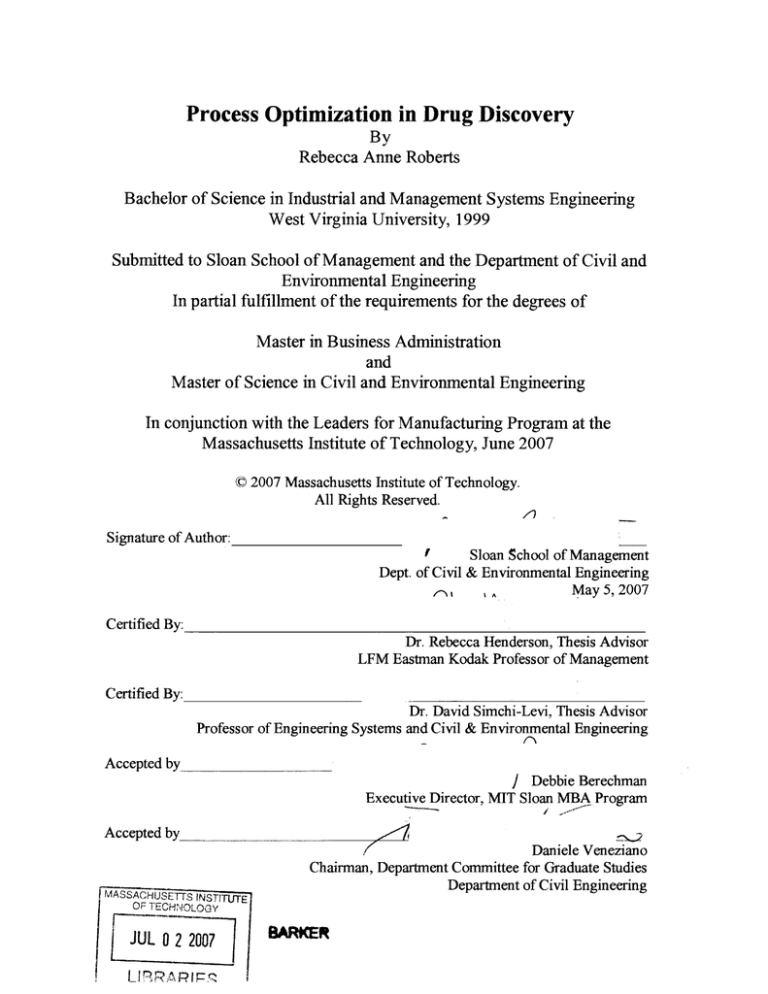

Process Optimization in Drug Discovery

advertisement