U.S. COMBAT RESCUE OPERATIONS: 1970-1980 by Michael Cox

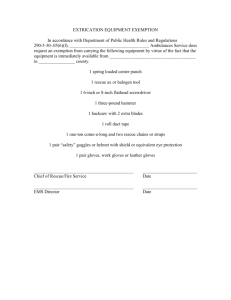

advertisement