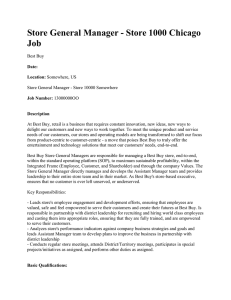

Document 10835168

advertisement