Is Cost Competitiveness a Prerequisite for Growth? -

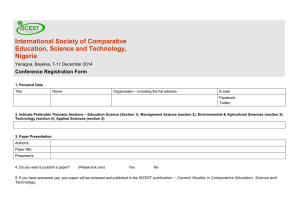

advertisement