The Economic and Financial Feasibility of Food Innovation Centers

By

Alison Crowley

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE

OF TECHNOLOLGY

JUN 29 2015

LIBRARIES

B.A. in English

Georgetown University

Washington, DC (2010)

Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning

in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of

Master in City Planning

and

Master of Science in Real Estate Development

at the

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY

June 2015

@ 2015 Alison Crowley. All Rights Reserved

The author hereby grants to MIT the permission to reproduce and to distribute

publicly paper and electronic copies of the thesis document in whole or in part in

any medium now known or hereafter created.

Author

Signature redacted

Department of Urban Studies and Planning and Center for Real Estate

May 21, 20

Certified by

Signature redacted

Dr. Andrea Chegut

Center for Real Estate

Accepted by.

Signature redacted

Thesis Supervisor

Professor Dennis Frenchman

Chair, MCP Committee

Department of Urban Studies and Planning

Accepted by

Signature redacted

_____

Professor Albert Saiz

Chair, MSRED Committee

Interdepartmental Degree Program in Real Estate Development

The Economic and Financial Feasibility of Food Innovation Centers

By

but leases to individual tenants operating one of the FIC business

Alison Crowley

components. Financing largely comes from the philanthropic sector, and

Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning on May 21,

some of the most ambitious FICs have partnered with municipalities to

2015 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master in

identify publicly owned land for a nominal ground lease to the city or below-

City Planning and Master of Science in Real Estate Development

market acquisition.

Overall, the FIC product type is still under development, and more

ABSTRACT

must be learned about the lease structures within the PC to generate more

robust underwriting standards that will better attract commercial investment.

A Food Innovation Center (FIC) is an enclosed commercial space

The most proprietary component of FICs are indoor vertical farms, for which

comprising a mix of complementary uses pertaining to locally-operated food

the technology supporting the farm systems is still very much in the nascent

growing, production, processing, testing, distribution, and sale. These uses

R&D phase and not yet prepared for commercial diffusion.

include indoor vertical farms, commercial shared-use kitchens for start-up

FICs do, however, have the ability to impact urban residents who

food businesses, rooftop greenhouses, food halls with local, artisanal vendors,

lack access to healthy food. Through procurement, distribution, and

and food-related R&D space, among others.

wholesaling operations that can take place at FICs, regional small farmers can

While literature exists on the demand for locally produced food,

more easily get their produce into an urban area for distribution to residents.

there is still a gap in the industry's knowledge about the financing

Incubator kitchens can provide cost-effective means for urban residents to

environment, development costs, and overall rate of success that FICs

test their own business models in the food and beverage manufacturing

experience. The research presented in this thesis is intended to provide an

industry, and the roles that FICs play in hosting public events increases the

overview of existing Food Innovation Centers via data on acquisition,

connection between consumers and the food they eat. FICs generate

construction, operations, and returns of individual projects. Does the FIC

economic growth through their ability to launch small businesses and create

product innovation add value to urban industrial real estate, and is the FIC a

stronger and more direct supply chains between farmers, producers,

feasible model, financially and economically, for industrial development?

wholesalers, food and beverage providers, and ultimately the consumer.

Survey analysis of 62 FICs and six in-depth case studies show that

FICs are more prominently featured in commercial rather than industrial

Thesis Supervisor: Andrea Chegut

space and operate on a business model in which a developer owns the property

Title: Postdoctoral Research Associate

3

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

To my inspiring cohort of friends in DC and around the world, who

cheered me on when I made the leap and moved to Cambridge.

To the DUSP, CRE, and GSD communities, for two years of

challenging conversations, fulfilling projects, & terrific happy hours.

To my advisor, Andrea Chegut, for pushing me to think ever more

critically about this strange interest of mine, and for providing

thought-provoking and encouraging feedback every step of the way.

And to my mom, who answered every phone call and never wavered

in her support and encouragement of my efforts at MIT and in life.

Thank you!

4

CONTENTS

Tables and Figures

8

1. Introduction

9

Results

12

Organization

13

2. Food and Industry in America

Background: Food and Industry

14

15

FoodAccess

15

FoodRenaissance

17

America's IndustrialEconomy

19

3. Food Innovation Centers

23

The Economic and Financial Feasibility of Food Innovation Centers

25

Components of a FIC

28

Kitchen Incubators

28

Vertical Farms

30

FoodHubs

35

FoodR&D

35

FIC Proposals

37

Food Commons Hub

37

Los Angeles River Urban Agriculture Plan

37

FoodInnovation District

40

Conclusion

41

5

4. Survey Analysis

42

Data

42

Methodology

43

Descriptive Statistics

44

Analysis

52

Conclusion

60

5. Case Studies of Food Innovation Centers

62

Data

62

Methodology

62

Case Studies

65

GrandRapids Downtown Market

65

Crop Circle Kitchen - PearlFacility

71

The Plant

76

West Louisville Food Port

81

Baltimore FoodHub

85

RainierBeach Innovation District

88

Conclusion

6. The Future of Food Innovation Centers

The Economics of Food Innovation Centers

92

96

98

Process Level: AgriculturalR&D

98

Firm Level: Economic cluster effects

100

The Financial Feasibility of Food Innovation Centers

102

Suggestions for Further Research

104

Conclusion

104

6

Applications to Foodand Industry

104

The Futureof FoodInnovation Centers

106

Appendices

109

Appendix A: Copy of Survey

109

Appendix B: Companies Contacted

113

Appendix C: Interview Questions

122

Image Sources

124

Bibliography

125

7

TABLES

Figure 4.9:

Construction Financing Sources for Renters and

Owners

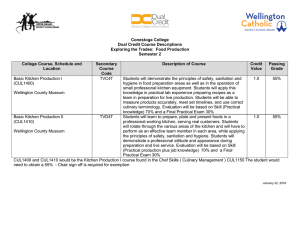

Chapter 3

Table 3.1:

Potential Uses Within a Food Innovation Center

Table 3.2:

Building Uses Combined with ZFarming

Figure 4.10:

Construction Costs for Building Owners

Figure 4.11:

Financial Structure of Firms

Figure 4.12:

Annual Net Operating Income by Percentage of

Firms Responding

Chapter 4

Table 4.1:

Business Operations Included in Survey

Table 4.2:

Lease Rates Reported by Building Renters

Chapter 5

Table 5.1:

Profiles of Case Study FICs

Table 5.2:

Summary of Key Take-Aways

Table 5.3:

Summary of Development Costs, Capital Structure, and

Lease Structures

FIGURES

Figure 4.13:

Average NOI: By Location

Figure 4.14:

Average NOI: By Number of Business Operations

Figure 4.15:

Average NOI: By Building Ownership

Figure 4.16:

Average NOI: By Capital Structure

Figure 4.17:

Average NOI: By Firm Ownership

Figure 4.18:

Income Level by Location

Figure 4.19:

Income Level by Number of Business Operations

Figure 4.20:

Income Level by Building Ownership

Figure 4.21:

Income Level by Firm Ownership

Figure 4.22:

Income Level by Rental Rates

Figure 4.18:

Average Percent of Operating Expenses Covered by

Revenue: By Location

Figure 4.19:

Average Percent of Operating Expenses Covered by

Chapter 4

Figure 4.1:

Development Project Phases

Figure 4.2:

Geographic Location by Density

Figure 4.3:

Geographic Location by Region

Figure 4.4:

Primary Business Operations by Geographic

Context

Figure 4.5:

Building Ownership

Figure 4.6:

Building Typology by Building Ownership

Figure 4.7:

Building Typology of Urban Firms

Figure 4.8:

Construction Financing Sources for Building Owners

Revenue: By Number of Business Operations

Figure 4.20:

Average Percent of Operating Expenses Covered by

Revenue: By Building Ownership

Figure 4.21:

Average Percent of Operating Expenses Covered by

Revenue: By Capital Structure

Figure 4.22:

Average Percent of Operating Expenses Covered by

Revenue: By Firm Ownership

Figure 4.28:

Capital Structure by Business Ownership (n = 32)

8

projects: a desire to engage local farmers, manufacturers, and

entrepreneurs in the process of creating and sustaining a regional food

system.

Interest in FICs continues to grow, not only from the real

estate development community, but also from the design community,

from

conventional

and

investors,

community-oriented

to

municipalities, customers, and the food business entrepreneurs

themselves. Not only in the United States, the concept has taken hold

abroad as well, in particular in western Europe and Asia, where

1

industrial revitalization in the former and experimental vertical

Introduction

farming in the latter have been the primary motivations for innovation.

In the design community, nationally and globally recognized

This thesis will explore the confluence of urban food

firms like Perkins + Will and OMA Architects have published master

manufacturing and industrial re-use through the lens of the real estate

plans completely centered on the development of urban food

developer. Specifically, I will examine the economic and financial

manufacturing space, speaking to the desire of stakeholders to

feasibility of the development of Food Innovation Centers. A Food

recognize

Innovation Center (FIC) is an enclosed commercial space, in either

competitions have also featured food: the Philadelphia Center for

a mix of

Architecture awarded its 2015 Better Philadelphia Challenge first

complementary uses pertaining to locally-operated food growing,

prize to a team of graduate architect and planning students who re-

production, processing, testing, distribution, and sale.

envisioned a 292-acre island in the Delaware River as the "Delaware

new construction

or adaptive

re-use, comprising

FICs are an expanding product type at the nexus of the urban

transformative

development

through

Valley Foodworx." Their proposal included

food.

Design

food distribution

agriculture and commercial real estate sectors of the economy. There

warehouses, an agricultural college, a seed bank, a farmers market, and

are many variations, but a certain fundamental holds true for the

at its centerpiece, a vertical farm.1

A vertical farm is located in buildings with highly controlled environmental

conditions and access that house year-round crop production in artificial

environments. "2015 Better Philadelphia Challenge Winners Announced,"

Philadelphia Center for Architecture, December 10, 2014, accessed April 1,

1

9

dNhrn'

farming, a nascent industry with financial promise, began to attract

r"llf)"

FOO0DWO

-. ,

RXNuue

Wr'

,,

_

Sustain

,

r

investment in 2014 and 2015. AeroFarms, a vertical farm started in

e I

2004, announced in March 2015 that it would partner with the RBH

Tree canopy

Group, Goldman Sachs Urban Investment Group, and Prudential

Financial, as well as the City of Newark and the New Jersey Economic

Resafency

Development Authority to invest $30 million into the conversion of a

69,000 former steel factory into a vertical farm. The facility, soon to

Transworation

be the largest vertical farm in the United States, was under

construction as of March 2015.2 Significantly, this project represents

PublicRelm

one of the first instances in which a conventional, market-rate investor

has taken on an industrial rehabilitation project for vertical farming.

Hardaspe

SITE PROGRAMMING

PHASING

Other vertical farms continue to announce acquisitions and

expansions for their businesses as well: in February 2015, hydroponic

indoor farming company Urban Organics announced the acquisition

of an 80,000 SF former brewery in St. Paul, MN,3 while Green Spirit

Farms, one of the larger vertical farm producers in the country, secured

"~

the acquisition of a 300,000 SF industrial facility in Lackawanna

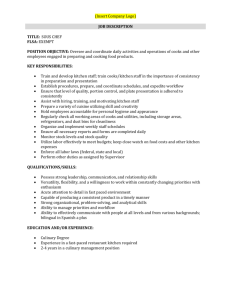

Image 1: The siteplanforFoodworx includes a verticalfarm, agriculturalcollege, and

distributioncenter.

Conventional and community-oriented financing continues

to connect with FICs at a slow but growing pace. In particular, vertical

2015, http://philadelphiacfa.org/blog/2015-better-philadelphia-challengewinners-announced.

Jessica Mazzola, "$30M 'vertical farm' to bring jobs to Newark, fresh

greens to N.J., developers say," NJ.com, March 9, 2015, accessed April 1,

2015,

http://www.nj.com/essex/index.ssf/2015/03/30mverticalfarmtobringjobs

_fresh greens tone.html.

Kristen Leigh Painter, "Urban fish farm expanding in St. Paul," St. Paul Star

Tribune, February 17, 2015, accessed March 15, 2015,

http://www.startribune.com/local/stpaul/292310561 .html?page=1 &c=y.

10

County, Pennsylvania, for a $27 million investment in a new vertical

Examples of this include the Pennsylvania Governor's Action Team,

farm.4

a collaboration of the PA Department of Community and Economic

Municipalities have been key players in making these projects

happen. Vertical Harvest, a three-story vertical greenhouse under

construction in Jackson, Wyoming, represents

Development, which helped organize and finance the Green Spirit

Farms transaction in Lackawanna County.

a $3.7 million

investment made possible by the donation of publicly owned land to a

non-profit operator and a nominal $1 annual rent to the city. Vertical

Harvest leveraged these cost savings to secure $750,000 in debt

5

financing by backing loans with private investors' collateral. Whether

municipalities offer to ground lease or sell sites for less than market

value, the sheer scale of underutilized city-owned land has inspired

many local governments to work with interested developers and

entrepreneurs to make these food-related projects happen. Some

cities, like Philadelphia and Detroit, have made utilizing vacant land

for food production purposes a key tenant of their blighted land

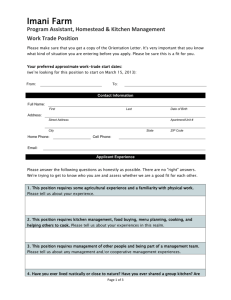

Image 2: Rendering of VerticalHarvest, agreenhouse to be built on the back side ofa

parkinggarage inJackson, WY.

remediation plans, while others have implemented zoning and land

use policies friendly toward mixed-use

commercial

and light

manufacturing.

At the federal level, programs such as New Market Tax

Credits and the Healthy Food Financing Initiative provide financing

and local and state-level initiatives work to identify grants and loans

to make available to developers pursuing innovative food projects.

"Green Spirit Farms LLC to Establish Operations in Lackawanna County,

Creating 101 Jobs," Bloomberg Business, December 12, 2013, accessed

February 10, 2015,

Most significantly, interest from entrepreneurs continues to

grow, both from the development community and from the actual

small and mid-sized food production and manufacturing community

as well. Developers are taking note of the increasing wave of interest

in locally grown, manufactured, produced, distilled, and brewed

goods, and food-based entrepreneurs continue to emerge as an

http://www.bloomberg.com/research/stocks/pivate/snapshot.asp?privcapid=

234779303.

Penny McBride and Nona Yehia, telephone interview with Vertical Harvest

founders, February 16, 2015.

11

important part of America's manufacturing renaissance. Brought

industrial space and operate on a business model in which a developer

together, the Food Innovation Center movement represents a new

owns the property but leases to individual tenants operating one of the

way of thinking about food production. FICs represent opportunity in

FIC business components. FICs operate on average at least three

the economic language of innovation districts and regional growth

separate business components, and some surveyed operated as many

clusters, in the financing language of return on investment, and in the

as 12. Data on construction costs for building owners shows that

cultural language of broadening access to locally sourced and produced

industrial rehabilitation may be less financially feasible than

food throughout America.

demolition and new construction on industrial sites, or alternatively,

While literature exists on the demand for food produced in

less financially feasible than rehabilitating a commercial space instead.

such an environment, there is still a gap in the industry's knowledge

Financing for FIC development largely comes from the

about the financing environment, development costs, and overall rate

philanthropic sector, and some of the most ambitious FICs have

of success that FICs experience. This lack of information is to the

partnered with municipalities to identify publicly owned land for a

detriment of the developers, business owners, or city officials who may

nominal ground lease to the city or below-market acquisition.

consider developing a Food Innovation Center in their own city.

Commercial investment in FICs focuses more specifically on indoor

The research presented in this thesis is intended to provide an

vertical farms rather than any of the alternative FIC uses, and those

overview of existing Food Innovation Centers via data on acquisition,

FICs that operate primarily as shared-use kitchens typically earn less

construction, operations, and returns of individual projects. Is the FIC

than $5,000 in annual net operating income. All of the FICs surveyed

a feasible model, financially and economically, for industrial

who provided income data earned on average $161,415 annually.

development? Additionally, does the FIC effectively address issues of

Overall, the FIC product type is still under development, and

food access and transparency that confront urban stakeholders? These

more must be learned about the lease structures within the FIC to

research questions will guide the thesis.

generate more robust underwriting standards that will better attract

commercial investment. The most proprietary component of FICs are

Results

indoor vertical farms, for which the technology supporting the farm

Survey analysis of 62 FICs and six in-depth case studies show

that FICs are more prominently featured in commercial rather than

systems is still very much in the nascent R&D phase and not yet

prepared for commercial diffusion.

12

FICs do, however, have the ability to impact urban residents

In Chapter 4, 1 analyze a quantitative survey distributed to 190

who lack access to healthy food. Through procurement, distribution,

companies that I identified as Food Innovation Centers based on the

and wholesaling operations that can take place at FICs, regional small

operational definition provided in Chapter 2. The survey requested

farmers can more easily get their produce into an urban area for

information on location, firm ownership structure, building ownership

distribution to residents. Incubator kitchens can provide cost-effective

structure, building typology, development costs, business operations,

means for urban residents to test their own business models in the food

operational costs, and net operating income. The data collected is used

and beverage manufacturing industry, and the roles that FICs play in

to produce descriptive statistics on a representative sample of FICs in

hosting public events and cooking demonstrations as well as providing

the United States.

space for food trucks to serve meals increases the connection between

In Chapter 5, I conduct in-depth interviews with developers

consumers and the food they eat. FICs generate economic growth

of six Food Innovation Centers. These interviews document details

through their ability to launch small businesses and create stronger and

related to the acquisition, construction, financing, and operations of

more direct supply chains between farmers, producers, wholesalers,

these projects. The interview method addressed some of the

food and beverage providers, and ultimately the consumer.

complexity in financing and business operations not easily captured in

the survey responses. Using the case studies, I draw a series of

Organization

This thesis is organized as follows. In Chapter 2, I do a

takeaways relevant to the feasibility of FIC development from the real

estate developer's perspective.

literature review to assess the policy and planning issues that FICs are

Finally, in Chapter 6, I conclude with a review of the research

best prepared to address from the perspective of the urban resident and

conducted and how this research applies to the issues identified in

real estate developer. In Chapter 3, I continue the literature review to

earlier chapters. I respond to the question of the economic and

understand current research on the component business operations of

financial feasibility of Food Innovation Centers through the lenses of

a FIC and existing FIC proposals. In this chapter, I seek to understand

agricultural innovation, economic clustering, and rent premiums. I

the relevant development costs and financial feasibility associated with

end with a summary of the best practice model for developing a Food

each of the FIC's business operations.

Innovation Center.

13

Among all of these challenges, at least two revolutions are

underway in the American city: the increasing scrutiny of our food

supply, including where it comes from, how it's made, and who it

reaches, as well as increasing innovation within a changing industrial

and manufacturing sector. The attention and reflection paid to both

issues in today's policy environment represents a unique and timely

opportunity for the real estate development community. For

2

developers pursuing projects in infill, urban locations, food and

Food and Industry in America

industry have the potential to provide substantial returns in the form

of an emerging product: the Food Innovation Center.

Urbanized areas, particularly urban industrial cores or inner

cities, are confronted with a variety of issues: growing income

The US Department of Agriculture describes a food value

chain as the following:

inequality, disappearing middle class job opportunities, lack of

"Food value chains are collaborative business networks

workforce and lower income housing, and disparate access to healthy,

comprising

affordable food, among many others. Entrepreneurs operating in these

marketers, and buyers who jointly plan and coordinate their

environments have identified innovative solutions that challenge the

activities to achieve common financial goals while advancing

political and financial status quo, from developing co-working spaces

an agreed-upon set of social or environmental values, such as

for start-up companies, to sending mobile food trucks carrying fresh

farmland preservation, sustainable agriculture, small farm

produce into the poorest urban communities, to democratizing access

viability, or healthy food access."6

to capital for small business owners through microfinance lending, and

Food Innovation Centers harness the value chain in one

a myriad of other means.

food

producers,

processors,

distributors,

physical product. They are not a completely new concept, but a

singular definition for the product does not exist. Variously called food

Barham, James, et al, "Regional Food Hub Resource Guide," US

Department of Agriculture Agricultural Marketing Service, April 2012,

accessed February 5, 2015, http://dx-doi-org/10.9752/MS046.04-2012.

6

14

hubs, food innovation districts and food innovation campuses, and

Background: Food and Industry

food ports, the basic concept of a FIC capitalizes on the same

agglomeration

synergies

that

characterize

technology-based

FoodAccess

innovation districts, but does so for the food and beverage

The world's population of 7.2 billion in 2013 could increase

manufacturing and production sector. For the purposes of this

by as much as one billion people in the next twelve years and an

research, the FIC typology is defined as the following:

additional 1.5 billion by 2050.7 The majority of that growth will take

A Food Innovation Center is an enclosed commercial space,

place in rapidly urbanizing developing countries. In the United States,

in either new construction or adaptive re-use, comprising a

despite less dramatic shifts in overall population, cities continue to see

mix of complementary uses pertaining to locally-operated

greater growth than surrounding suburbs and rural communities.

food growing, production, processing, testing, distribution,

Urban areas account for 80.7 percent of the US population, up from

and sale.

79 percent in 2000, and the nation's urban population grew by 12.1

The FIC product provides the physical infrastructure for small

percent between 2000 and 2010, outpacing the overall 9.7 percent

and mid-sized farms and food manufacturers and entrepreneurs to

national growth rate.' Between 2012 and 2013, cities with populations

operate and grow their businesses by sharing the burden of capital

exceeding 100,000 residents collectively added an additional 857,000

expenses across multiple users. FICs strengthen regional agricultural

residents, accounting for an increase of one percent, while all other

systems by creating a closed-loop system of production that serves the

areas of the country reported just a 0.6 percent growth rate in total.9

needs of both producers and consumers, and also have the potential to

Food access, however, does not seem to be keeping pace with

put back into productive use the industrial building stock in distressed

the numbers moving into cities, and lack of access to fresh food is more

urban areas.

problematic for low-income urban neighborhoods than high-income

ones. The US Department of Agriculture tracks census tracts known

as "food deserts," defined as a tract in which a substantial share of

Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population

Division, 'World Population Prospects: The 2012 Revision, Volume I:

Comprehensive Tables ST/ESA/SER.A/336," 2013, accessed March 1,

2015, http://esa.un.org/wpp/documentation/pdf/wpp2012_highlights.pdf.

I "Growth in Urban Population Outpaces Rest of Nation, Census Bureau

Reports," US Census Bureau, March 26, 2012, accessed April 13, 2015,

I United

https://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/2010_census/cbl250.html.

I Mike Maciag, "New Population Estimates Highlight Nation's FastestGrowing Cities," Goveming, May 22, 2014, accessed March 1, 2015,

http://www.governing.com/news/headlines/gov-population-estimateshighlight-nations-fastest-growing-cities.html#data.

15

residents living in low-income areas also have low levels of access to a

This disparity has very real economic implications. In the

large supermarket or an affordable food retail outlet. Access is based

United States, where energy and transportation costs account for eight

on whether 33 percent or more of the tract residents live more than

percent of the price of domestically produced food," volatility in oil

one mile from a supermarket or large grocery store. In New York,

prices can severely affect weekly spending if food prices spike.

where the urban population grew by 0.7 percent between 2012 and

Although US oil prices in February 2015 at $49.56 per barrel were 53

2013, none of the Census tracts in Manhattan identify as a food desert,

percent lower in real value than seven years earlier in February 2008,

while nine Census tracts in the Bronx, a substantially lower income

they rose as high as $143.71 per barrel in June 2008 and could deviate

borough of the city, qualify."

as much again.1 5 For those without vehicles living in food deserts,

These statistics appear to repeat themselves in every major

residents may turn to either fast food or corner markets for their main

metropolitan area of the United States. In Washington, DC, where

consumption needs. Corner markets and bodegas frequently have

population increased by 2.1 percent between 2012 and 2013,11

fewer fresh food options and much higher price points due to the lack

residents of the two poorest wards of the city, Wards 7 and 8, who

comprise only 25 percent of the city's overall population, comprised

of economy of scale from which small business owners suffer. Indeed,

the average price of a standard dry good otherwise found in a typical

53 percent of the total number of residents living in food deserts in

supermarket has an 11 percent mark-up when sold at an individually

that city.' 2 In Los Angeles, neighborhoods in high-income areas had

owned corner market (Broda, Leibtag, Weinstein, 2009). In both

2.3 times as many supermarkets per household as those in low-income

circumstances then, for residents both with and without access to a

neighborhoods." Again, the USDA shows that lower income

car, living in a food desert can have substantial impacts on both their

communities in urban areas have fewer supermarket-grade food

health and income.

options than their wealthier neighbors.

m "USDA Food Deserts," United States Department of Agriculture, accessed

January 10, 2015, http://apps.ams.usda.gov/fooddeserts/fooddeserts.aspx.

1 Maciag, "New Population Estimates Highlight Nation's Fastest-Growing

Cities."

"USDA Food Deserts."

" Sarah Treuhaft and Allison Karpyn, "The Grocery Gap: Who has Access to

Healthy Food and Why It Matters," PolicyLink and The Food Trust, 2010,

accessed 25 Februrary 2015,

http://thefoodtrust.org/uploads/media items/grocerygap.original.pdf.

"1 Chris Aresenault, "Will the world's hungry benefit from falling oil prices?"

Reuters, January 12, 2015, accessed February 15, 2015,

http://www.reuters.com/article/2015/01/12/us-food-oil-hungeridUSKBNOKL1 KU20150112. Accessed 5 March 2015.

" "Crude Oil Price History Chart," Macrotrends, accessed 5 March 2015,

http://www.macrotrends.net/1369/crude-oil-price-history-chart.

16

FoodRenaissance

Right next to neighborhoods plagued by lack of food access is

food in US farm policy that the reasons cited for the increasing

popularity of local foods were the following:

a renaissance underway in how consumers think about food. Since the

"[...] [P]erceived higher product quality and freshness of local

early 2000s, the exploding popularity of farmers markets, food trucks,

food; a desire to provide social and political support for local

direct producer-to-consumer marketing, and most significantly the

farmers and the local economy; farmland preservation;

growth of the organic food industry points to a growing consumer

concerns about environmental impacts and energy use and the

interest in where food comes from, how it's produced, and who

perception that local foods are more environmentally friendly

ultimately benefits from food sales. In 2008, the USDA estimated that

(limited use of chemicals, energy-based fertilizers, and

the farm-level value of local food sales totaled about $4.8 billion,

pesticides); perceived better food safety given shorter supply

representing 1.6 percent of the overall US food market. Of the $4.8

chains; sense of social justice (perceived fairer labor prices and

billion direct-to-consumer sales, farmers markets accounted for $0.9

fair price for farmers); knowing the source of the product; a

billion. Another $2.7 billion in sales were filled through local grocers,

commitment to establishing closer connections between

restaurants, and regional distributors, and $1.2 billion came from

consumers and agricultural producers; and, generally, a

farms using direct and intermediated marketing channels, such as

response to concerns

Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) subscriptions (Johnson,

agriculture."

Aussenberg, Cowan, 2013). For the ten years between 1997 and 2007,

Other signs point to an increased interest in the origination

direct-to-consumer marketing increased in all US food-producing

and quality of the food we consume. Food trucks, typically operated

regions and represents a small but increasingly popular alternative to

by entrepreneurial chefs who lack the capital to start a brick-and-

mainstream supermarkets. Notably, in 2010, the USDA reported

mortar restaurant, continue to multiply annually. Food truck sales in

6,132 farmers markets registered in the country. By 2015, that number

2012 totaled approximately $650 million and were projected to grow

grew to 8,268, a 35 percent increase.1 6 Johnson, Aussenberg, and

to $2.7 billion in revenue by 2017, representing three to four percent

about industrialized

commercial

Cowan (2013) found in an analysis for Congress on the role of local

"Farmers Markets and Local Food Marketing," United States Department

of Agriculture, accessed January 10, 2015,

http://www.ams.usda.gov/AMSv1.0/ams.fetchTemplateData.do?template=Te

6

mplateS&leftNav=WholesaleandFarmersMarkets&page=WFMFarmersMark

etGrowth&description=Farmers+Market+Growth.

17

of total US restaurant food sales." Many of these trucks market the

competition from other organic retailers selling at slightly lower price

fact that their ingredients are locally sourced, and many operators have

points, Whole Foods still reported a rise in fiscal first quarter sales in

contracts directly with the growers producing the food they sell.

February 2015, with total sales rising 10 percent to $4.67 billion, and

However, the greatest sea change in the consumer's

same-store sales rising 4.5 percent. After opening nine more stores in

perception of food has come from the explosive growth of the organic

the first quarter of 2015 alone, Whole Foods predicts that there is still

industry. The USDA's National Organic Program stipulates that

enough demand in the US for organic products to warrant 1,200 more

organic agricultural products must be produced through approved

stores.

methods that exclude synthetic fertilizers, sewage sludge, irradiation,

subsequent increase in the price of food; in January 2013, the

and genetic engineering." According to the USDA Economic

wholesale price of standard organic commodities was on average 92%

Research Service, organic food sales in 2012 totaled approximately $28

more expensive than their conventional counterparts.23 This price

billion, an 11 percent increase from 2011 and a four percent share of

point increase even greater reflects the contrast between issues of food

total food sales. 9 The Organic Trade Association reported slightly

access in inner city urban cores and the growing local and sustainable

higher sales for 2012, totaling $31.5 billion, with an increase of an

food movement.

A caveat to the increasing popularity of organic foods is the

additional $4 billion in sales by the end of 2013.20 Whole Foods, which

In short, despite the overwhelming dominance of the

has dominated the organic niche since it first opened in 1985 and

traditional grocery store, change is underway. The 25 largest food and

whose name remains synonymous with the organic food industry,

opened 32 stores in 10 new markets in 2013 alone." Despite increased

beverage companies in the US collectively represented 45 percent of

7 Steve King and Carolyn Ockels, "Food Trucks Motor into the Mainstream,"

December 5, 2012, accessed March 5, 2015,

http://network.intuit.com/2012/12/05/food-trucks-motor-into-the-mainstream/.

1s "National Organic Program," USDA Agricultural Marketing Service,

December 12, 2014, accessed May 6, 2015,

http://www.ams.usda.gov/AMSvl.0/nop.

19 Catherine Greene, "Growth Patterns in the US Organic Industry," USDA

Economic Research Service, October 24, 2013, accessed March 5, 2015,

http://www.ers.usda.gov/amber-waves/2013-october/growth-patterns-in-theus-organic-industry.aspx#.VPjLFYuhNUQ.

2 "Market Analysis," Organic Trade Association, accessed March 5, 2015,

https://www.ota.com/what-ota-does/market-analysis.

'1Panos Mourdoukoutas, "Has Whole Foods' Growth Peaked?" Forbes, July

31, 2014, accessed February 25, 2015,

http://www.forbes.com/sites/panosmourdoukoutas/2014/07/31 /has-wholefoods-growth-peaked/.

22 Lauren Gensler, "Whole Foods Reports Strong Sales Growth, Expansion

Into Canada," Forbes, February 11, 2015, accessed February 25, 2015,

http://www.forbes.com/sites/laurengensler/2015/02/1 1/whole-foods-reportsstrong-sales-growth-expansion-into-canada/.

23 "Wholesale vegetable prices, organic and conventional, monthly and

annual, 2012-2013," USDA Economic Research Service, August 28, 2014,

accessed May 6, 2015, http://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/organicprices.aspx.

the industry's $418 billion in 2014 sales, but this number was 4.3

18

percentage points less than five years earlier. In comparison, smaller

279,000 jobs between 2013 and 2014. Overall US industrial

companies focused on local and organic branding strategies saw their

production increased 5.6 percent year-over-year between the fourth

share of the industry increase from 32 percent to 35 percent in the

quarter of 2013 and the fourth quarter of 2014.25 Robust industrial

same period. Consumers continue to respond positively to increasing

growth in 2014 has had dramatic effects on the country's industrial

transparency documenting where their food comes from, what the

building stock, resulting in lower vacancy rates, higher asking rents,

ingredients mean, and how their produce and meats were farmed.

and positive net absorption of industrial building stock in 2014.

This, next to the trials of residents living in food deserts with limited

Leasing activity increased by 5.6 percent between 2013 and 2014,

access to affordable food, frames two of the most significant

while asking rents increased from $5.28 per square foot to $5.54 PSF

developments regarding food in urban America.

on a national average, a 4.9 percent increase. In certain sub-markets

like Southern California, vacancy rates for warehouses are as low as

America's IndustrialEconomy

3.4 percent, compared to a national average of seven percent.

While cities grapple with questions of food provision and

These market fundamentals drove increased levels of new

quality, the re-emergence of manufacturing and an increased interest

industrial construction in 2013 and 2014. In 2014, new development

in "re-shoring" American industry represents another potential

included 74.5 million square feet of speculative industrial space and

renaissance, and one that ties neatly into the issues of food access and

67.2 million square feet of build-to-suit. This was an increase of 54

transparency. This section will first discuss the areas in which

million square feet over construction activity in 2013. On the

industrial development is experiencing growth, and conclude with a

transactions side, industrial transaction volume ended 2014 at $54.2

description of the current strategies in place for increasing urban

billion, a 13.2 percent increase over the previous year. Over the last

industrial manufacturing and how FICs fit into this urban strategy.

five years, the average price has increased by 48.1 percent, and the

Due in large part to the growth of e-commerce, employment

average cap rate continued to decline, dropping to seven percent in

in the manufacturing, warehousing, and distribution industries added

2014.26 Los Angeles, Chicago, and Atlanta are three of the strongest

Leslie Josephs and Annie Gasparro, "Balance of Power Shifts in

Groceries," Wall Street Joumal, March 26, 2015, accessed March 29, 2015,

2

24

http://www.wsj.com/articles/balance-of-power-shifts-in-groceries1427414817.

Tina Arambulo, "Marketbeat: Q4 2014 Industrial Snapshot: United States,"

Cushman & Wakefield, 2015, accessed March 5, 2015,

http://www.recenter.tamu.edu/mdata/pdf/US_1ndustrialCushmanWakefield.

pdf.

Tina Arambulo, "Marketbeat: Q4 2014 Industrial Snapshot: United States."

'

19

urban industrial markets, where leasing activity increased as much as

51 percent between 2013 and 2014.

Maker spaces are generally understood to be creative, do-ityourself spaces with work space flexibility where users create, invent,

There is a disparity, however, between the strong numbers

and build through investing in communal tools and equipment that a

reported on the industrial sector overall, and the reality of industry in

single entrepreneurial manufacturer may not be able to purchase alone.

urban cores. Sector growth has occurred largely in the suburban and

They operate both in more traditional realms of manufacturing such

peri-urban realm of warehousing and logistics, rather than in

as woodworking and metallurgy, as well as in the tech sphere, working

traditional urban manufacturing. Within Los Angeles, which had the

on hardware and software development utilizing 3D printing, rapid

strongest industrial leasing activity in 2014, 160,332 addresses in 2012

prototyping, and other electronics.

were registered as vacant commercial addresses. In Chicago, another

A number of municipalities have explicitly identified maker

strong industrial market with more than 1.1 billion square feet of

spaces as an economic development priority. In the Brooklyn

industrial space, 37.9 percent of commercial properties were vacant

neighborhood of Red Hook, a planning process begun in 2013 called

(Eppig and Brachman, 2014). While these numbers account for all

Bridging Gowanus resulted in a planning framework that includes a

commercial buildings, including office and retail, a significant portion

recommendation for mixed-use zoning that would only allow new

of entirely vacant buildings are underutilized and abandoned industrial

residential development provided the developers include in the project

building stock in urban cores.

compatible light manufacturing space, art/artisan work space, or non-

The underutilization of industrial building stock has captured

profit organization work space.2 ' This concept is also reflected in

the interest of municipalities who have begun to develop strategies for

Detroit's 2013 planning framework, Detroit Future City, which

increasing urban industrial manufacturing. These strategies are more

emphasizes mixing light industrial with residential and retail

granular than the large-scale industrial growth occurring in the e-

development. Beyond Brooklyn and Detroit, formerly industrial

commerce and warehousing industries, and instead highlight light

communities like Somerville, MA, Lexington, KY, Oakland, CA, and

manufacturing and "maker spaces" as a means of revitalizing these

Philadelphia, PA, as well as more progressive cities like San Francisco

brownfield properties.

describe adopting policies to promote maker space communities in

John Schaefer, "Bridging Gowanus' Community Planning Framework

Details Shared Values and Planning Recommendations for the Future of the

2014, accessed 25 March 2015, http://brdginggowanus.com/wpcontent/uploads/2014/1 1/Bridging-Gowanus-Press-Release-FINAL.pdf.

27

Gowanus Canal Area," Bridging Gowanus press release, November 21,

20

recently published city plans between 2013 and 2015.2" Zoning

manufacturing and processing plants employed more than 11.5

updates that encourage mixed-use commercial/industrial zones, as

million people, representing about 14 percent of all US manufacturing

well as codes that specifically allow for or even require light

and one percent of all US non-farm employment.29 Within this sector,

manufacturing near residential are indicative of the growing

the Bureau of Labor Statistics tracks several sub-groups, including

willingness of municipalities to embrace non-invasive industry.

Fruit and Vegetable Preserving and Specialty Food Manufacturing,

Sugar and Confectionery Product Manufacturing, Bakeries and

niche products represent a viable evolution of the industrial sector

Tortilla Manufacturing, and Other Food Manufacturing. All of these

outside of the big-box warehousing needs of e-commerce, the low

sub-groups continue to reflect growth year over year. Significantly,

level ofjobs generated through these efforts cannot effectively respond

these jobs tend to accept lower-skilled workers, primarily those

to the whole issue of revitalizing American manufacturing. One of the

without postgraduate degrees, but also have higher median wages than

other major sectors of industry is food manufacturing, and it is within

typical low-skill positions.3

"

While artisan wood-crafting and light manufacturing of

this sector, and alongside that of artisans and craftsmen, that creative

Due to the growth trajectory of the food manufacturing sector

entrepreneurs can operate. In 2011, more than 30,000 food

and its job creation potential, this sector has gained traction as a

2 Somerville, MA's mayor Joseph Curtatone submitted a proposed zoning

ordinance to the city's aldermen in January 2015 proposing changes to the

zoning that included the creation of new "fabrication districts": areas zoned

specifically for artisan production, exhibition, sales, and shared workspaces.

Source: "Proposed Somerville Zoning Ordinance Includes Ambitious

Inclusionary Housing Requirement;s Zones to Support Arts/Maker

Economy," City of Somerville, MA, January 14, 2015, accessed April 22,

2015, http://www.somervillema.gov/news/overhauled-zoning-ordinancesubmitted-aldermen. In October 2014, the Planning Commission of

Lexington, KY, voted to approve the creation of a Planned Unit Development

in downtown Lexington that would allow the construction of the city's first

maker space, a $5 million development over three blocks called LuigART

Maker's Spaces. The PUD approval would include updates to the city's

zoning ordinance that included new land use definitions such as "digital

makerspace," "artisan food and beverage production," and "artisan

manufacturing." Source: "LuigART Makers Spaces," Fayette Alliance,

September 18, 2014, accessed April 22, 2015,

http://fayettealliance.com/luigart-makers-spaces/. In Oakland, a thriving

makers community formed the advocacy organization Oakland Makers,

which continues to press the city to preserve industrial zoning, promote

businesses with tax breaks, and help makers advertise their products.

Source: James Reddick, "Oakland's makers get organized," Oakland North,

December 9, 2013, accessed April 21, 2015,

https://oaklandnorth.net/201 3/1 2/09/oaklands-makers-get-organized/. In

February 2014, Philadelphia planners examined an update to the zoning

code that would create two new classifications, Industrial Commercial Mixed

Use (ICMX) and Industrial Residential Mixed Use (IRMX) to promote the

maker space economy. Similarly, in San Francisco, the city continues to

protect production and distribution space in the eastern portion of the city

through zoning. Source: JoAnn Greco, "Making Way for 'Makers,"' Planning,

February 2014, accessed April 15, 2015,

http://preface.com/pdf/MakingWayforMakers.pdf.

29 Stephen Martinez, "Food and beverage manufacturing," US Department of

Agriculture, October 27, 2014, accessed March 8, 2015,

http://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-markets-prices/processingmarketing/manufacturing.aspx.

3 "Industries at a Glance: Food Manufacturing: NAICS 311," US Department

of Labor, accessed March 4, 2015, http://www.bis.gov/iag/tgs/iag311.htm.

21

potential solution to combat industrial blight, to aid in cities' efforts

to bring manufacturing back into the urban core, and to address the

issues of food access and quality addressed above. For the real estate

development community, a Food Innovation Center may respond to

these disparate needs while generating economic value.

22

have managed to scale to the level of commercially viable food

production, but the majority remain as ground or rooftop-level

community gardens."

Innovation districts, in contrast, are geographic areas where

anchor institutions and companies "cluster and connect with start-ups,

business incubators, and accelerators" (Katz and Wagner, 2014),

primarily in the technology and life sciences sectors. They specifically

3

aim to focus on new products, technologies, and market solutions

Food Innovation Centers

through the convergence

of young start-up companies with

established, well-capitalized firms and venture capital financiers in one

The FIC combines two emerging urban movements: urban

physical space. Innovation districts, typified by Boston's Seaport

agriculture and innovation districts. Urban agriculture is primarily

District and Barcelona's 22@ District, frequently are located in

understood to be the re-use of vacant lots and rooftops into productive

underutilized industrial neighborhoods with historic building stock.

gardening spaces. These spaces typically do not generate substantial

They empower entrepreneurs by reducing overhead costs through co-

revenue, but instead serve as community development tools by

working spaces and connecting entrepreneurs with funders, and they

reducing blight, promoting educational awareness of how food is

are envisioned

grown, providing a way for community members to gain new skills,

technically-wired" (Katz and Wagner, 2014).

as "physically compact, transit-accessible,

and

and simply creating a safe public space for neighbors to gather. In

The Food Innovation Center draws from both of these

situations where the economic climate of a community is such that

movements by taking the innovation district approach and applying it

vacant land cannot feasibly support new development, urban

to urban agriculture. However, because the FIC utilizes its interior

agriculture represents a low-cost alternative to putting that land back

space as actively as it does its exterior grounds and rooftops, the

to some form of productive use. Some urban agriculture movements

product can offer significantly more uses than just a community

A famous example of an urban agriculture project that has grown to

commercially viable production levels is Growing Power, a system of urban

farms founded in Milwaukee, MN, that now has multiple sites in Wisconsin

and Illinois and produces more than one million pounds of fresh food

annually. Source: "About," Growing Power, accessed April 20, 2015,

http://www.growingpower.org.

31

23

garden, all of which are defined below in Table 3.1. Where one single

Table 3.1: Potential Uses Within a Food Innovation Center

building captures this diverse mix of uses, this thesis will refer to the

project as a FIC. In an instance where the project involves multiple

Use

buildings clustered together in a campus-like setting, this thesis will

Farm Production:

use the terminology "Food Innovation District," or FID, to

Vertical farming

distinguish the single building from the campus-like cluster.

Regardless of whether the uses are housed in one FIC or spread

Rooftop gardening

Outdoor plant production utilizing

rooftop surfaces.

Hydroponics

enhancing local food security and putting industrial building stock

back to productive use remains the same.

Indoor plant production utilizing a

mix of natural and artificial lighting.

throughout a FID, the nature of the development programming and

the underlying ethos of promoting food manufacturing as a means of

Definition

The process of growing plants in

sand, gravel, or liquid without soil.

Aquaponics

A productive FIC will incorporate the greatest variety of these

System of aquaculture in which the

waste produced by farmed fish or

uses, particularly between farm production, incubator kitchen value-

other

add processing, and retail. Examples of operational FICs comprise a

nutrients

mix of public and private spaces, where ideas and goods can be

hydroponically, which purifies the

developed and produced within privately leased spaces but also shared

water in which the fish are grown.

and marketed to the public and among entrepreneurs via programmed

Value-addftodprocessing

public space. FICs can have a single developer-owner operating in a

Incubator kitchen

aquatic

Shared-use

for

animals

supplies

plants

grown

commercial

kitchen

single commercial building. However, other FICs may emerge as a

specifically rented at below-market

mix of owners consciously co-locate their businesses into the same

rates to start-up food production

physical area, organically creating a cluster of business development.

businesses.

Commissary kitchen

Commercial kitchen in which on-site

staff prepare and store foods for

24

outside clients, such as food truck

Food Hall

sell foods grown or processed on-site

owners and small restaurateurs.

as separate vendors.

Packagingand Warehousing

Storage

Co-packing

Commercial area in which FIC users

Storage facilities for small businesses

Educational

to store batches of food prior to sale

Business

Consulting

in the form of freezers, coolers, and

development/technical

businesses on product development,

dry storage space.

assistance

accounting, marketing,

package

products

owners'

business

according

to

for

small

and other

elements of business planning.

Services in which on-site staff process

and

services

Classroom component

Demonstration and teaching space

showcasing on-site processes and

their

technologies.

specifications.

R&D and Testing

Food laboratory

New product development, with onsite services such as shelf life analysis,

Though many FICs currently exist in the form of incubator

nutrition analysis, safety testing, and

kitchens and small-scale growing operations utilizing indoor

allergen testing.

production technologies, it remains unclear if these initiatives will ever

move beyond the grassroots to the wider realm of private sector, for-

Retail

Farmers Market

Caf6/Restaurant

The Economic and Financial Feasibility of FICs

Direct producer-to-consumer sales of

profit real estate investment and development. The leap into more

farm products and specialty processed

conventional commercial real estate could be constrained by matters

foods.

of economic supply and demand for the product as well as the financial

On-site food service establishment

realities of making a FIC profitable; this thesis seeks to clarify that

serving foods grown or processed in

constraint through an economic and financial analysis of existing

house.

projects.

25

The challenges for development of this model are many. The

operations, but the product type is a poor fit for traditional

Initiative for a Competitive Inner City breaks these challenges down

into six major categories, all of which a FIC must tackle and overcome

to achieve success. These categories include the following:"

1. Space: FICs must find affordable spaces that aren't too large

lenders.

6.

Complexity: FICs must contend with oversight by multiple

city and federal agencies, requiring a detailed understanding

of codes and regulations.

at the start-up phase, but have growth options as business

In a review of innovative food trends in North America,

operations expand. This can be difficult in cities with limited

Pansing et al (2013) found that the top growth areas in the food sector

and costly real estate.

are local and/or regional food, including local seafood, local produce,

2. Distribution: The economics of small volume distribution are

hyper-local sourcing, and farm-branded products. Despite the fact

challenging, and FICs must advise producers in navigating

that the food sector is growing at twice the rate of the national

sophisticated channels of distribution.

economy, the authors found

Costs: Rising utility and input costs, wages, particularly in

management skills, business models that don't match early stage

unionized areas, and tax burdens all must be accounted for in

investor expectations, and a lack of understanding of the "unique

the business plan.

nature of the food sector among established lenders" has caused the

3.

that shortcomings

in business

4. Income density: Consumer demand is largely pre-defined

sector to struggle to identify financing. In a scan of all of the various

based on the population density and income levels. For FICs

food sector innovations present in the market today, the authors found

that target properties in low-income neighborhoods for cost

that combining food start-up incubators with a retail component-

reasons, the project must still generate enough demand from

one of the fundamental use mixes in a FIC-can actually generate

higher-income communities to remain sustainable.

investment-worthy returns. Co-locating start-up businesses that fulfill

5. Financing: FICs require sizable up-front investments in both

different roles in the food production process can be economically

the facility and capital equipment required to begin

beneficial, as companies benefit from shared infrastructure and avoid

32 Initiative for a Competitive Inner City, Karp Resources, and Next Street,

"Designing an Inner City Food Cluster Strategy," (presentation to the Inner

City Economic Summit, October 4, 2011), accessed February 2, 2015,

http://www.icic.org/ee _uploads/pdf/Designing-an InnerCityFood_Cluster

StrategyICICSummit.pdf.

26

Overall, the FIC can resemble any number of projects, from

time consuming permitting costs as well as diversify their revenue

those as small-scale as single incubator kitchens helping scale

sources and capture the value added by related businesses."

Similarly, companies in a food cluster can take advantage of

entrepreneurial food businesses, to hundred-acre redevelopment

"inner cities' central locations, access to multi-modal transportation

schemes capitalizing on the growing local food manufacturing

hubs and [...] under-utilized manufacturing and warehouse space" to

industry. The majority of FICs lie somewhere in between these two

develop successful food innovation centers with multiple business

extremes, and will be examined via survey and interviews in the next

operation components.

4

two chapters.

in

The literature studying FICs as they are defined here is

and

limited. Much more research has been done on some of the specific

commercial restaurants. Increasing the capacity of small scale,

operational components of the FIC, in particular on incubator

entrepreneurial food manufacturing businesses, attracting large-scale

kitchens, indoor vertical farming, food hubs, and anchor-led food

processing and production facilities, and incorporating urban

R&D facilities. Understanding the economic and financial feasibility

agriculture could create a viable business plan for a FIC. Additionally,

of the individual uses within a FIC is equally important to

building the infrastructure for a thriving public/private market and

understanding the value of the entire space.

ICIC identifies food cluster growth opportunities

production,

distribution,

and institutional

food

service

expanding alternative distribution models would bring more revenue

for small business owners who operate at the facility. These

distribution

models include

connecting small producers with

distributors who specialize in small buyers, brokers who coordinate

logistics for large buyers, and direct delivery services. 35

33

Cynthia Pansing, et al, "North American Food Sector, Part One: Program

Scan & Literature Review."

3 Initiative for a Competitive Inner City and US Conference of Mayors,

"Growing Healthy Economies: Leveraging America's Urban Food Cluster,"

2013, accessed February 10, 2015,

http://www.icic.org/ee-uploads/publications/ICICRESEARCHUSCM_2013

Initiative for a Competitive Inner City, Karp Resources, and Next Street,

"Designing an Inner City Food Cluster Strategy," (presentation to the Inner

City Economic Summit, October 4, 2011), accessed February 2, 2015,

http://www.icic.org/ee uploads/pdf/Designing-anInnerCityFood_Cluster_

StrategyICICSummit.pdf.

3

_REV1.pdf.

27

Components of a FIC

The study determined seven distinct lessons relevant to

incubator kitchen success based on their surveys. These facts included

the ability for operators to customize the facility to fit the needs of its

Kitchen Incubators

Kitchen incubators have existed in the United States since at

users; developing automated systems for scheduling kitchen rental

least 1979.36 Since then, incubators-both kitchen and non-kitchen

times to avoid mismanagement and human error; offering business

alike-have formed more than 19,000 new businesses and added more

development courses and micro-lending to ensure client success;

than 245,000 jobs to the economy, according to some accounts."

helping manage marketing and procurement contracts for clients;

In a survey of 46 shared-use kitchen incubators, Heller (2013)

offering co-packing and distribution services on-site; partnering with

found that the majority operated as for-profit enterprises with annual

regulatory agencies to ensure efficient permitting for the kitchen; and

budgets of less than $100,000. Only 19 percent of the kitchens

lastly, adopting multiple revenue streams for a reliable business cash

surveyed utilized grants as a source of revenue, but only 31 percent of

flow. 3 8

the businesses reported being profitable; half broke even, while 16

percent reported losing money.

Buckley et al (2014) published a case study of an incubator

kitchen located in Hart, MI. The kitchen, Starting Block, opened in

Regarding their physical space, half of the respondents stated

2006 and employs three part-time staff members in a building

that their facility was between 1,000 and 3,000 SF, with an average

measuring 10,900 SF. The business runs a 2,500 SF commercial

rental kitchen size of 1,673 SF. Nearly three-quarters of the kitchens

kitchen, 600 SF catering kitchen, around 5,450 SF of rented office

provide some kind of business support services; the most common

space and meeting rooms, and warehouse and storage space. An initial

forms

with

feasibility study estimated the cost to begin operations to be $1.2

licensing/permits/insurance, and assistance with sourcing ingredients.

million ($220 PSF), but due to volunteer labor hours and fundraising,

of

assistance

were

one-on-one

coaching,

help

the Starting Block was able to start the business at one-third the

16Annabelle Allen et al., "Rainier Beach Food Innovation Center: Kitchen

Incubator Business Model for City of Seattle Community Development

Planning," Seattle Department of Planning and Development, 2014,

accessed January 5, 2015,

http://www.seattle.gov/dpd/cs/groups/pan/@pan/documents/webinformatio

nal/p2165050.pdf.

1 Annabelle Allen et al., "Rainier Beach Food Innovation Center: Kitchen

Incubator Business Model for City of Seattle Community Development

Planning."

38 Gregory Heller et al, "US Kitchen Incubators: An Industry Snapshot," Econsult

Solutions, Inc, August 5, 2013, accessed March 9, 2015,

http://www.econsultsolutions.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/ESISharedKitchenReport_2013.pdf.

28

projected cost. Project financing was received through the USDA

Rural Development's Rural Business Enterprise Grant, as well as

through six county commissions and a grant from Michigan State

University. To obtain a building, the Starting Block team formed a

partnership with the City Manager of Hart and identified a facility

:dl

that could be leased at a low rate from the city.

Despite cost-saving measures that allowed operations to

commence on schedule, the kitchen faces a number of obstacles.

Client wish lists for automated equipment, better packaging

equipment, and coding software like Universal Product Code (UPC)

are capital costs that the kitchen was unable to bear at the time the

study was completed. Further, despite robust demand, kitchen rental

e4,,4,

fees will only cover 30 to 40 percent of the facility's cash flow, even

when fully booked; as a result, the owners must turn to entrepreneurial

income streams, such as business counseling and education courses,

that lie outside the business's primary operation.

In a feasibility study for a kitchen incubator in the Rainier

Beach Innovation District in Seattle, Washington, Allen et al (2014)

proposed a FIC that would consist of one or two buildings and house

commissary and training kitchens, along with a cafe, classroom, and

additional facilities for education and business training purposes. The

study showed that the most common size for a kitchen incubator is

...

luccen~emberaL268

odufpact-7gubipace

Image 3: Proposed layout ofDC's Union Kitchen incubatorkitchen.

between 1,000 and 3,000 SF, and based on a survey of similar projects

around the country, development costs for a new construction building

29

would total approximately $8 million and require $100,000 in annual

2. Indoor farms utilizing greenhouse technology with ample

operating costs. The authors identify a number of income stream

sunlight, but incorporating some amount of artificial lighting

opportunities outside of kitchen rental fees that incubators could

and potentially utilizing hydroponic or aquaponic farming

undertake to close the gap between costs and revenue. These include

technology.

efforts by La Cocina Kitchen in San Francisco, CA, which uses

3. The adaptive re-use of an industrial building for indoor plant

cooking classes, night markets, a media dinner, gift bazaar,

production and fish farming, which typically utilizes almost

conferences, festivals, and an online marketplace to generate income;

entirely artificial lighting and growing systems.

the Chefs Center of California in Pasadena, CA, which rents retail

4. Vertical farm skyscraper, envisioned as the new construction

space to food trucks; and CropCircle Kitchen in Dorchester, MA,

who has a direct partnership with a local food distributor for sourcing,

of a building intended entirely for food production, of which

warehousing, and distribution, increasing value to its clients and

In common vernacular, and best suited to the FIC, vertical

ultimately demanding a higher premium for shared space.39

only a few selective projects in Asia truly qualify today.

farms are defined as "multistory buildings with highly controlled

environmental conditions and access that house year-round crop

VerticalFarms

Vertical farms exist on a very diverse spectrum, but are most

traditionally viewed as one of the following physical typologies, from

most conservative to most radical:

production

in artificial

environments

by using

hydroponics,

aeroponics, and aquaponics."4 ' To that end, farms housed within a

FIC will most closely resemble the third typology on the spectrum.

In one of the most comprehensive reviews of existing

1. The traditional greenhouse, which proliferates in agriculture

literature on the subject, Specht et al (2013) utilized the term

today and uses entirely soil-based, sunlight-based farming

"ZFarming," which stands for "zero-acreage farming" to define "all

techniques.

types of urban agriculture characterized by the non-use of farmland or

open space, thereby differentiating building-related forms of urban

* Annabelle Allen et al., "Rainier Beach Food Innovation Center: Kitchen

Incubator Business Model for City of Seattle Community Development

Planning."

* Clemson University Institute of Applied Ecology, "Charleston Vertical Farm

Design Feasibility Study," (report prepared for the US Environmental

Protection Agency, November 2011), accessed February 3, 2015,

http://media.clemson.edu/public/restoration/iae/vfarm/cuiae-epa vfreport3O

mb.pdf.

41 For the purposes of this report, rooftop gardens and rooftop greenhouses

are only considered if they are incorporated into a FIC whose interior uses

also include a mix of the required uses defined in Chapter 2.

30

agriculture from those in parks, gardens, urban wastelands, and so on."

Table 3.2: Building uses combined with ZFarming

This includes rooftop gardens, rooftop greenhouses, edible facades,

and indoor farms. The authors reviewed 96 publications on the

Building Use

Absolute frequency

subject, concluding that ZFarms, in all of their forms, could promise

Health

1

positive environmental benefits from the reduction and recycling of

Transportation facilities

4

waste, social benefits from improving community food security,

Industry/warehouse

3

providing educational facilities, and linking consumers more directly

Mixed-use

5

to food production. Of the 96 academic articles studied on the subject,

Retail

7

27 addressed how ZFarming can be integrated into existing buildings

Community services

7

through construction and retrofitting, while 22 discussed project

Office

7

feasibility and the issues of investment cost and financing.

Housing

9

In a follow-up review working from Specht et al (2013)'s

Farming-related food business

10

definition, Thomaier et al (2014) identified 73 ZFarming projects

Research/education

10

located in North America, Europe, and Asia, 17 of which were

Hotel/restaurant

11

specifically indoor farms. The remaining 56 projects were a

combination of rooftop gardens, rooftop greenhouses,

fagade

The authors also created five ZFarm typologies, described

treatments, and other. Of the 73 projects, the majority did not include

below. Of these five, the first two, "commercial Zfarming" and

any other use besides the farm itself. The authors identified the spread

"Zfarming as innovation incubator," are most likely to be the kind of

of building uses shown in Table 3.2 that were combined with

vertical farm housed inside a Food Innovation Center.

ZFarming projects, but did not clarify whether any of these uses were

1.

Commercial ZFarming: An operation in which the main

combined specifically with an indoor farm-the subject of this

purpose is to be economically viable, typically operated by a

section-versus a rooftop garden, rooftop greenhouse, or fagade

start-up. The operation works either on a "retail-affiliated" or

treatment.

"independent" business model, the former which primarily

cooperates with one specific retailer, while the latter typically

31

Image 4: FarmedHere, a 90,000 SFfacility in Chicago.

uses various distribution channels and may be more oriented

hydroponics and aquaponics rather than traditional soil-based

toward the community and open to the public.

farming.

2. ZFarming as innovation incubator: Operations that are

3. Image-oriented ZFarming: A business in which the farming

typically pioneer or demonstration projects operated by non-

operation is not the main source of revenue, but serves as an

profit organizations or research institutions. They promote

"add-on" to a food business, largely for marketing or PR

"innovative concepts of food production and sustainable ways

purposes.

of organizing urban life and consumption" and typically utilize

32

4. Social and educational ZFarming: A business whose main

Institute of Applied Ecology working for the US Environmental

purpose is to "communicate social and education values,"

Protection Agency (2011) selected a former paper factory in

largely found at educational and social institutions. An

Charleston, SC, to study the feasibility of an adaptively reused vertical

example of this could be a rooftop garden on top of a charter

farm. The analysis cited unique elements like alternative energy

school, or a community-oriented garden.

sources, urban watershed impact reduction, and cyberinfrastructure

ZFarmingforurban living quality: Largely private farms that

technology as reasons beyond increased agricultural production to

are incorporated into residential or commercial projects as an

pursue vertical farming. Due to the energy required to control the