Document 10821285

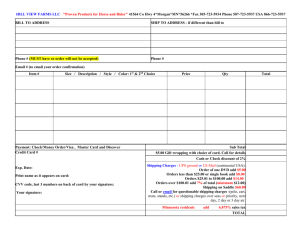

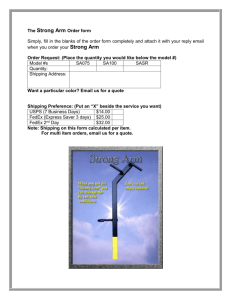

advertisement