The Distribution of National Income and the Role of Capital Market Imperfections DRAFT

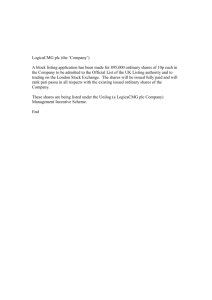

advertisement