The Early Bird gets the Worm? Birth Order

advertisement

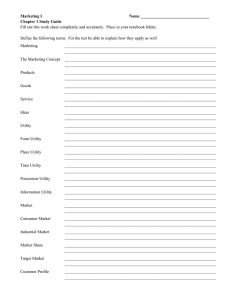

Abstract

The Early Bird gets the Worm? Birth Order

E¤ects in a Dynamic Model of the Family

Elisabeth Gugl and Linda Welling

This version: May 2008

Abstract

Birth order e¤ects are found in empirical work, but lack theoretical foundations. Our new approach to modelling children provides this. Each child has

the same genetic make-up and parents do not favour a child based on its birth

order. Each child’s needs change as it grows, and births are sequential. At any

point in time siblings are at di¤erent developmental stages, and the bene…ts

of parental investment di¤er across these stages. Parental time investment in

children lowers current and future wages; this opportunity cost varies across

time. Birth order e¤ects emerge from the interaction of the changing bene…ts

and costs of parental investment.

JEL: D13, D91, J13.

This is a substantially revised version of a paper presented at the Western

Economic Association International 82nd annual conference, Seattle June 29July 3, 2007. We thank Joseph Price, our discussant, whose comments suggested

this re-orientation of the paper, and two anonymous referees.

Both authors’ address: Department of Economics, University of Victoria,

P.O. Box 1700 STN CSC, Victoria, BC, V8W 2Y2, fax: (250) 721 6214, Gugl:

phone: (250)721 8538, email: egugl@uvic.ca; Welling: phone: (250) 721 8546,

e-mail: lwelling@uvic.ca.

1

"The great advantage of living in a large family is that early lesson of life’s essential unfairness." ~Nancy Mitford (http://www.quotegarden.com/family.html)

1

Introduction

Recent empirical literature has found signi…cant di¤erences between …rst-born

and later-born children in both outcomes - such as educational attainment

and/or earnings (Ejrnæs and Pörtner 2004, Black et al. 2005, Conley and

Glauber 2006, Kantarevic and Mechoulan 2006) - and inputs (Price 2008).

Since family resources, both …nancial and time, are viewed as largely responsible for these e¤ects, much of this literature has attempted to separate the

e¤ects of birth order from family size. Hanushek (1992) suggests that these

di¤erences arise because children of di¤erent birth order within the same family

are born into di¤erent family con…gurations, with di¤erent intellectual environments. There are few theoretical economic models in which birth order e¤ects

emerge endogenously; this is not altogether surprising, since our models are typically atemporal when it comes to investment in children. The only empirical

paper investigating a possible cause for a birth order e¤ect is Price (2008). The

author looks at quality time that parents spend with each child in multiple child

families, and …nds that children of higher birth order receive less quality time

at any given age than did their earlier-born siblings at the same age. This does

not necessarily imply that younger siblings receive worse education within the

family than older children because siblings replace some of the quality time that

parents would otherwise spend with them; however, younger siblings lack the

opportunity to be teachers from an early age on (this was suggested by Zajonc

1976). Our paper …lls an important gap in the theoretical literature on families

with children by investigating how child quality is produced in the family and

how birth order may in‡uence the conditions of producing child quality for each

child.

We investigate the trade-o¤ parents make between spending time with di¤erent children and working for income (to purchase consumption goods for family

members). Parents care about both the contemporaneous utility of each child,

and their well-being as adults. We consider a three stage model of parenthood.

Two children are born and mature sequentially. Each child spends two periods

with their parents: the …rst born is a single child in its …rst period of life, and

an older sibling in its second; the second born is a younger sibling in its …rst

period, and the sole child in the household in its second. Thus each child spends

one period with parents and a sibling, and one period alone with its parents.

Older children have di¤erent needs than younger ones, so the sequential nature

of child rearing matters.

Our model is based on four assumptions about child development:

(1) Children develop in stages, and their needs change as they grow. While

this is clearly an oversimpli…cation, we distinguish two periods in a dependent

child’s life. In the …rst period a child’s dominant need is time spent with them;

2

in the second period, parental time remains an essential input, but the child

also needs consumption goods. These inputs a¤ect both contemporaneous

child utility and the child’s human capital when grown. This is consistent with

Waldfogel (2006), who summarizes evidence that suggests that interaction with

the mother (primarily) is of primary importance in the …rst three years, whereas

for the second half of the pre-school years good nutritional habits and socialization with peers becomes important as well.1 In a recent series of papers

Cunha &Heckman (2007), along with various co-authors, have emphasized that

the psychological literature tells us that human capital is multi-dimensional (at

least cognitive and non-cognitive), and investment at particular stages/ages of

childhood can be critical for adult ability in di¤erent dimensions. Cunha &

Heckman (2007) present a stylized theoretical model with two stages of childhood and two of adulthood. More than one stage of childhood is important

in their model because the production technology in the second stage may depend on inputs in the …rst stage, and …nal adult utility may be a¤ected by this

cumulative investment.

(2) Parental child care has an opportunity cost of foregone current and future earnings. The time each parent spends caring for a child has an impact

on parents’future wage rates and, therefore, on the potential earnings of each

parent once the child is grown. While this "family wage gap’is well-documented

empirically2 , most of the theoretical literature has overlooked this aspect; Willis

(1973) is an early exception. Cunha & Heckman (2007) follow tradition in this:

parents supply labour inelastically, so there are no labour market/family income

implications of early versus late investment for the family of origin. We explicitly incorporate both current and future implications of this time investment in

a dynamic framework.

(3) Child care can be provided by parents, or purchased, but parental time

is more valuable in producing child quality than is the same amount of time

provided by others. There is a large empirical literature emphasizing the importance of parental (or more often maternal) time spent with the very young

child.3 However, theoretical models have not yet captured this distinction.

(4) Child bearing is sequential. In most models parents choose quality and

quantity simultaneously. Sequential childbearing and di¤erent needs of children of di¤erent ages suggest that multiple children should be viewed as joint

products in household production, with the production mix varying over time.

Our model makes explicit the sequential nature of decisions. Ejrnæs and Pörtner (2004) consider sequential fertility, with parents deciding on future children

once they observe the nature of the current infant. Parents determine investments in these children once all are born. We abstract from the "nature" side,

and assume all children are identical at birth; parental investment begins im1 See

also Huang(2006) and Keane and Wolpin (2007) for related results.

references - waldfogel has papers in mid/late 90’s; since then, many papers on various (all?) western countries, some in Japan....."...women work shorter hours when they have

children and are, if anything, paid less per hour than comparable women without children"

Waldfogel (2006: 13)

3 See, for example, Ruhm (1998, 2000).

2 Need

3

mediately. Thus the …rst-born receives parental investment before the second

child arrives, and investment in the last-born continues after the …rst-born is

fully grown and self-su¢ cient.

We show that both the …nancial and time investments parents make in their

children typically di¤er with birth order. These di¤erences arise because the

opportunity cost of parental child care varies over time, depending on the current

wage rate, the anticipated growth in wages over time, and the particular inputs

required by children at each stage.

We focus on child-rearing, beginning with the birth of the …rst child. We

take as given that spouses achieve e¢ ciency in marriage - at least from this point

forward. Spouses could have entered a binding agreement at the beginning of

marriage or, starting with the arrival of the …rst child, bargained over life-time

utility. While our model can be extended to incorporate family bargaining, we

leave this to future research together with the analysis of changes in family

policies.

In the following section we …rst explain our basic three period model, and

specify our assumptions on child utility for respectively, young, older, and adult

children. We then set out our assumptions on parents. Parents receive utility

from their children through two mechanisms: …rst, they care about a child’s

current well-being, and second, they care about the adult well-being of their

children. Finally, we develop the contemporaneous budget constraints. Section

3 presents the results derived from solution of the parents’three-period decision

problem. Conclusions and extensions are in section 4.

2

The Basic Model

The family consists of a two adults and two children. Parents make decisions

over three periods. Births are deterministic and sequential: the …rst child is

born in the …rst period, and the second in the second period. A child spends

two periods with his or her parents, and then becomes a self-su¢ cient adult.4

The time path of family composition, then, is

Period 1(k = 1): wife (w), husband (h), young …rst-born

Period 2 (k = 2): wife, husband, older …rst-born, young second-born

Period 3 (k = 3): wife, husband, older second-born; independent older …rstborn.

Parents allocate their time between child care and work, and their earned

income between own and child consumption goods, in each of the three periods

to maximize the discounted present value of the sum of their individual utilities.

Let tjik denote the time parent i devotes to child j in period k = 1; 2; 3: Parents

care about their independent adult children as well as children living at home;

moreover, although they will not live to see it, they also care about the future

adult well-being of the second child. In this section we …rst describe the utility

4 In a fully dynamic model this third period would coincide with the …rst period, for the

next generation, of family life in our model.

4

functions of a child, then that of a parent. We then specify the household budget

constraints. In the next section we analyse the parents’decision problem.

2.1

Child’s utility

We di¤erentiate the …rst and second born children by superscripts: a denotes

the child born in the …rst period and b the child born in the second period. Let

ujk ; j = a; b denote the utility of child j in period k. We assume ub1 = 0 = ua3 :

in period k = 1 the unborn second child has utility of zero, and in period k = 3

the …rst born is an adult rather than a child, with a utility speci…ed in section

below.

Children live in the present: they have no memory of the past, and care

nothing about their future. Contemporaneous utility is produced di¤erently at

di¤erent ages of the child. While a dependent child j requires both time with

adults (tjk ) and consumption goods (xjk ), the relative importance of these two

broad categories changes as the child grows.

2.1.1

Young child

We take the extreme view that in the …rst period of life a child needs only

supervision equivalent to the time available to one adult; we normalize this

time to 1: Parents can provide child care themselves, or they can outsource by

hiring a nanny or enrolling the child in paid care. Let tjnk be the time a young

child spends in non-parental care in period k; k = 1; 2:5 Then the household’s

kth-period time constraint for a young child j is

tjwk + tjhk + tjnk = 1:

(1)

Utility depends on the time the parents spend with the child. Research on

early child development suggests that parental time is very important in terms

of the happiness of the child and we therefore assume that it produces higher

child utility than the same amount of time in other care.6 We assume parents

are perfect substitutes in child care, and focus on the sum tpk = twk + thk .

Using (1), assuming that parental time is more productive by a factor of p; the

utility in period k of a young child j is

ujk = Y (tjY k ); tjY k = (p

1)tjpk + 1; p > 1;

(2)

where Y ( ) is a strictly concave, at least twice di¤erentiable and increasing

function; in the appendix we make explicit further conditions su¢ cient to ensure

an interior solution for tY k :

5 Recall

there is no young child in the household in period 3.

more time with the child when young also increases a child’s skills and translates

into a higher earning potential when the child is grown. Parents care about their grown child’s

utility which is a function of the child’s earning potential. We discuss this point further below.

6 Spending

5

2.1.2

Older child

In the second period of life, a child no longer requires constant supervision; utility the child’s consumption of private goods as well as interaction with parents.7

As before, parents are perfect substitutes in child care. The utility in period k

of an older child j is

ujk = O tjpk ; xjck ;

(3)

where O ( ; ) is strictly concave, twice di¤erentiable and increasing in both

variables.

2.1.3

Adult child

After two periods as a dependant, the child becomes a self-su¢ cient adult who

requires no further input from the parents.8 Utility is a function of the child’s

earning potential, which is a function of the accumulated human capital of the

child. Human capital of the grown child depends on the parental time that

was spent with the child in each stage, as well as the amount of private goods

consumed by the older child. Given the sequential births, the …rst born becomes

an adult in period 3 while the second does not become self-su¢ cient until what

would be period 4. An adult child’s utility is a lump sum.

uaA

= A tap1 ; tap2 ; xa2

ubA

tbp2 ; tbp3 ; xb3

= A

(4)

where A ( ; ; ) is a strictly concave, at least twice di¤erentiable and increasing

function.

The presence in the second period of two children, of di¤erent ages and

with di¤erent needs, both requiring some supervision time, raises the issue of

economies of scope in child care: is a given amount of parental child care as productive if it is shared by two children, rather than devoted to one? Can parents

purchase child care for two children at the same rate as for one? Economies of

scope in supervision time implies that any detrimental e¤ects of sharing a caregiver with a sibling are compensated for by the bene…ts from sibling interaction.9

We assume economies of scope for the parents only, hence tap2 = tbp2 = tp2 :

7 While human capital as built up by the parents’ time spent with the child in the …rst

period feeds into the child’s earning potential and therefore third period utility of the child,

we assume that the happiness of a child in the second period is una¤ected by the time parents

have spent with it in the previous period. Of course this is an extreme assumption and past

parental time is very likely to in‡uence both human capital and child happinessin the current

period, but we …nd it reasonable to make a distinction between a child’s utility when it is still

a child and has a high discount factor and a child’s human capital that translates into utility

most signi…cantly in later periods.

8 Wishful thinking on our parts, no doubt. More seriously, we do not consider bequests.

9 If the children were twins, the appropriate concept would be economies of scale.

6

2.2

Parent’s utility

Parents obtain utility from their individual private consumption in period k

(denoted by xik ) as well as from the contemporaneous utility of any dependent

children. Thus the utility of parent i = w; h in period k = 1; 2; 3 is given by

uik = Uik (uak ; ubk ; xik )

(5)

In their planning parents also consider the well-being of their adult children,

so i’s intertemporal utility is given by

Ui = ui1 + ui2 + ui3 + uaA + ubA :

(6)

Parents have an intertemporal discount factor of 1, so their utility in future

periods weighs as heavily as the current period in their decisions. This implies

that they care about child utility tomorrow as much as they care about child

utility today. Moreover, parents treat each child’s utility over the child’s life

span equally.10 These assumptions would be natural in the case of twin births,

and are also appealing in the context of sequential births, because they guarantee

that parents will not favour their …rst-born because they value current utility

more than future utility. Of course, that does not guarantee identical treatment,

since the costs of producing child utility depend on the changing opportunity

cost of parents’time as well as the children’s developmental stages.

2.3

Full budget constraints

There are two uses for parental time: child care, and labour force participation.

In the …rst period, parent i is employed, for the amount of time lik = 1 tik , at

wage rate wi1 . The husband has an initial absolute advantage in earnings, so

ww1 < wh1 :The wage rate in each subsequent period is increasing in the time

spent in the labour force in the previous period:

wi2

wi3

= wi1 (1 + li1 ); > 0

= wi2 (1 + li2 ) = wi1 (1 + li1 )(1 + li2 )

(7)

Earnings in k = 2; 3 are therefore a function of past as well as current choices.

While the parents’wage rates grow, alternative child care can be purchased for

nk = n dollars per unit of time, and the private consumption good for both

parents and children has a unit price of 1 in each period. Thus the household’s

1 0 There are two obvious ways in which intertemporal discounting might enter here: parents

may value current utility more highly than future utility, at any point in time, and they might

weight more heavily the adult utilty of one or the other of their children. Introducing either,

or both, of these factors would alter our results in predictible ways.

7

budget constraints for each of the three periods are

h

a

xw

1 + x1 + ntn

a

b

xh2 + xw

2 + x2 + ntn

= ww1 lw1 + wh1 lh1 =

=

X

X

wj1 lj1

(8)

j=w;h

wj1 (1 + lj1 ) lj2

(9)

j=w;h

b

xh3 + xw

3 + x3

=

X

wj1 (1 + lj1 ) (1 + lj2 ) lj3

(10)

j=w;h

3

Parental Investment

We assume that parents’utility functions yield transferable utility, and therefore allocative e¢ ciency is independent of distribution. Maximizing the sum

of the parents’intertemporal utilities allows us to …nd the unique point in the

parents’production possibility set that yields Pareto e¢ ciency (Bergstrom and

Cornes 1981 and 1983). Maximizing this sum also uniquely determines the sum

h

of parental consumption, xpk = xw

k + xk ; k = 1; 2; 3. As parents are perfect

substitutes in the production of child utility, e¢ ciency dictates that the spouse

with the lower wage rate in period k is the primary caregiver, while the other

parent is the primary wage earner in that period. We assume parameters such

that the optimal time allocation has the latter working full time, and the former part-time, for pay; by construction the wife always provides parental child

care. Thus we have lhk = 1 and tpk = twk 2 (0; 1) ; k = 1; 2; 3 and therefore

tY k = (p 1)twk + 1.

The e¢ cient outcome is determined by the choices of time ftw1 ; tw2; tw3 g and

P3

private goods fxp1 ; xp2 ; xp3 ; xa2 ; xb3 g which maximize [ k=1 (uwk +uhk )+2(uaA +ubA )]

subject to the time and budget constraints above, given assumptions on the

nature of economies of scope. We consider two cases of transferable utility: i) quasi-linear utility, where parent i’s utility is additive in own consumption and child utility and there are no income e¤ects on spending on

the children, and ii) more general transferable utility which incorporates income e¤ects. In either case, the decision problem can be solved recursively:

third-period choices are functions of tw2 ; second-period choices are functions

of tw1 and …rst-period values can be found once the second-period value function is derived. These derivations are in Appendix A, as are all proofs. Assuming interior solutions in the third and second periods for twk , all third

and second-period choices are functions of …rst-period maternal child care,

tbw2 (tw1 ) ; taw2 (tw1 ) ; xa2 (tw1 ); xp2 (tw1 ); tw3 (tw1 ) ; xb3 (tw1 ); xp3 (tw1 ).

3.1

Quasi-linear utility

Let uik = xik + uak + ubk , i = w; h; k = 1; 2; 3:Then the household chooses private

consumption goods and the time allocation in each period to maximize:

8

3

X

(uwk + uhk ) + 2(uaA + ubB )

k=1

=

=

3

X

(xpk + 2(uak + ubk ) + 2(uaA + ubB )

k=1

[xp1 + 2Y (taY 1 )]

+[xp2 + 2 O(taw2 ; xa2 ) + Y tbY 2 ]

+[xp3 + 2O(tbw3 ; xb3 ) + 2(A(taw1 ; taw2 ; xa2 )

+ A(tbw2 ; tbw3 ; xb3 ))

subject to constraints (2) ; (3) ; and (4) :

We …rst state two results which clarify the source of the birth order e¤ects

in our model.

Lemma 1 With full economies of scope in maternal child care, so tw2 = taw2 =

tbw2 , and all else equal, the intertemporal opportunity cost of additional parental

child care is greater in the …rst period than in the second if and only if parental

child care time is greater in the …rst period than in the second.

Proof: see appendix

This relationship follows from the assumed intertemporal discount factor (of

unity), and the constant growth rate of parent i’s wages, given the previous

period’s labour force participation. In each of the …rst two periods, a young

child is present in the household, and the requirement of full-time care means

that parental child care time for this child has a within-period opportunity cost

of (wik n); k = 1; 2. The third period di¤ers because only an older child

is present, so the contemporaneous opportunity cost of parental child care is

higher in this …nal period than in the previous two.

Time spent in child care in the …rst period, out of the paid labour force,

lowers the wage rate in the second period, and hence lowers the opportunity

cost of parental time in that period. Similarly, when parents determine the …rst

period time allocation, they recognize that the greater the amount of time spent

at home in the second period, the less will be the income loss from lower second

period wages, and so the lower will be the opportunity cost of …rst period child

care time. This intertemporal feedback e¤ect will induce di¤erences in optimal

choices in the two periods, as is demonstrated by Lemma 2: .

Lemma 2 Suppose i) = 0, so future wage rates are independent of current

labour force participation; ii) maternal child care is a public input; and iii) the

utility of adult children is independent of their upbringing. Then i) taw1 < tw2 ;

ii) tbw3 < tw2 and iii) xa2 < xb3 if the cross partial for time and goods is negative

2

O

in the production of utility for the older child (so @x@j @t

0).

j

k

Proof: see appendix

9

wk

Thus the …rst born receives more attention when older than younger, while

this is reversed for the second-born. Moreover, the parents substitute goods

for time for the second born, while the reverse is true for the …rst born.

When there are no future labour market costs to parental child care, time

spent on child care in any period is indistinguishable from money. In this

case, only current bene…ts matter. If parents’spending on dependent children

a¤ects the latter’s adult utility, and parents consider this, then the complementarity of time and goods in this function also enters into the time allocation

determination.

Given the possibility of intertemporal substitution on the …nancial side, any

di¤erences in parents’choice of time in the …rst two periods will be determined

largely by the bene…ts accruing from child care time. The presence of two

children in the second period, but only one in the …rst, increases the bene…t of

second period time spent at home. Thus we have Proposition 1:

Proposition 1 With quasi-linear utility for parents, and full economies of

scope for the mother, the …rst-born and the second-born receive unequal treatment.

Proof: see appendix

Lemma 3 Suppose parental time is rival, and taw2 = tbw3 = 0. Then the

…rst order conditions for the parents’ decision problem can be satis…ed by equal

treatment for the two children: (taw1 ; xa2 ) = (tbw2 ; xb3 ):

Proof: see appendix

Thus, if parental time is rival, second period utility for children is such that

either they require no parental time in that period, and parents optimally choose

to devote no time to their children in this stage, then sequential child-bearing

does not necessarily give rise to birth order e¤ects. However, when parents

do spend time with both children at each stage, siblings receive di¤erent treatment even if parents care only about the contemporaneous utility of dependent

children.

Proposition 2 Suppose maternal time is rival, and parents choose to spend

time with each child in each stage. Then the …rst born receives more of both

maternal time and consumption goods than the second born, at each developmental stage.

Proof: (See Appendix)

Overall, this implies that the …rst born receives higher utility in each period

of her life and hence also enjoys a higher earning potential when grown-up. Note

that it is still possible to …nd tbw2

taw2 as Price does in his empirical work,

but his …nding that a signi…cant number of families spend equal time on both

children seems to be less plausible than when we assume maternal time is a

public input.

Given the same model except for maternal time being a public input in the

second period, we get tw2 > taw1 : This is not at odds with Price’s …ndings as

10

he restricts the children in the sample to be at least 3 years of age (check age

limit again). We argue that the second period starts right around this age as

pre-school now provides bene…ts that are complements to parental time and

so would …t better with our time-plus-consumption speci…cation of the second

period utility function of the child than the …rst period utility function.

3.2

Transferable utility with income e¤ects

Proposition 3 Suppose uaA = ubA = 0, so parents care about their children’s’

utility only while they are co-resident. Let uwk + uhk =

uak + ubk xpk +

a

b

2 uk + uk , so that utility is still transferable within the household but we now

have both an income e¤ ect and a substitution e¤ ect on child care time. Then

the …rst-born and the second-born child are treated di¤ erently.

Proof (see appendix)

Notice that "di¤erent treatment" is not necessarily "unequal treatment".

The …rst-order conditions for the private consumption goods of the two children

require that private goods are chosen to equalize the full impact of these goods

across the children. This suggests scope for di¤erent choices for the two children,

if parents choose di¤erent amounts of child care. First, recall that uaA and ua2

are both functions of both xa2 and tw2 , while ubA depends on the latter but not

the former, and ub3 depends only on third period choices. Thus, changes in time

and goods allocation in the second period which leave the FOC for xa2 satis…ed

will change third period choices.

3.3

Discussion of results

Consider the constellation of conditions which must hold if the two children

are treated identically. In our model, this means that each child receives the

same amount of parental child care as their sibling did in the same developmental stage, and the same amount of the private consumption good as their

sibling in the second stage: that is, (taw1 ; taw2 ; xa2 ) = (tbw2 ; tbw3 ; xb3 ). If maternal

time is a pure public input, so tbw2 = taw2 = tw2 , identical treatment implies

taw1 = tw2 = tbw3 : the mother spends the same amount of time in the labour

force in each of the three periods. Given positive returns to human capital acquisition in the labour market ( > 0) and constant prices for outsourced child

care and private consumption goods, this implies that full family income, and

the quantity of private consumption goods purchased, increases each period.

Identical treatment of the two children further implies that, since spending on

the older child’s private consumption is the same in the second and third periods, the parents consume more private goods in the third period than in the

second. Thus parents allocate all of the increase in full family income over time

to increased private consumption.

Why is identical treatment unlikely? In our setup, unless maternal child

care is purely rival, the contemporaneous bene…t of spending additional time

11

at home in the second period, caring for two children, is higher than the corresponding bene…t in the …rst period, when there is only one child. This suggests

that more time would be devoted to parental child care in the second period.

However, given the positive impact of current labour force participation on future market wages, there is also an intertemporal link between the periods, as

the opportunity cost of second period maternal care is decreasing in …rst period

maternal care. With no discounting, this increases the return to parental time

devoted to the young …rst born above that devoted to the young second born:

since there is no third child, no similar future bene…t increases the bene…t to

maternal time in the second period.

Clearly, these considerations change if the spacing between the births of

the two children is greater. Our model is presented in terms of two stages

of child development; nothing except more complex notation prevents us from

incorporating more stages. The changing opportunity cost of parental time and

the di¤erent needs of children at di¤erent stages will introduce birth order e¤ects

which depend on the alternative demands on parental resources at di¤erent

stages. The greater the spacing between children, the less likely it is that

demands will overlap, and the more siblings will resemble only children.

Using data from the American Time Use survey and restricting the age range

of children from 4 to 13, Price (2008) …nds that many parents spend equal time

with their children at any given point in time and that time spent with children

typically decreases from one period to the other (as the children grow older).

This is consistent with an extension of our model in which what is now called

the second period of a child’s life is split up into more periods in which children’s

needs for parental time play a lesser and lesser role as they grow. One could

also test our assumption of economies of scope by checking how often parents

spend time with one child while the other sibling is present.

4

Extensions and conclusions

This paper examines birth order e¤ects. Parents do not favour one child over the

other: each child in each of its developmental stages enters their intertemporal

utility function with the same utility weight. However, we do not require that

parents devote the same resources to each child in each developmental stage.

Central to our …ndings of birth order e¤ects is the assumption that investments

in children must begin at birth. Moreover children’s needs change as they grow,

so that parents deal with di¤erent production functions for child quality in any

period where children of di¤erent ages are present in the household.

4.1

Parents pay for early parenting "mistakes"

As emphasized before, our model does not explicitly incorporate the feedback

of earlier child quality on current child quality. Thus our model does not address the "critical" or "sensitive" periods for investment in certain dimensions

12

of human capital as in Cunha and Heckman (2007). Some aspects of this can

be incorporated by restricting the signs of the cross-partials of the utility function for the adult children, A(taw1 ; tw2 ; xa2 ) and A(tw2 ; tbw3 ; xb3 ) : the cumulative

e¤ects of investment appear if the marginal productivities of second period expenditures are increasing in the time spent with the young child. With the same

investment into the child in its second period of life, having spent less time in

the …rst period will lead to a lower marginal productivity of second-period investment. This reduces the negative impact of …rst-period parental child care on

the sum of second-period utility of the parents. Explicit use of CES functional

forms in our model would allow us to investigate the interaction of a deeper

model of child development with birth order e¤ects.

4.2

Adapting the CH model

Suppose now that the full extent of parental concern for children is captured

in a simpli…ed version of the CH human development model. In this case we

subsume the three functions for each child Y( ); O( ; ), and A( ; ; ) into a single

function:

ha

h

b

=

=

[ (taw1 ) + (1

[

(tbw2 )

+ (1

)(taw2 xa2 ) ]

1

)(tbw3 xb3 )

1

]

(11)

(12)

Retaining the quasi-linear form for parents’utility, the intertemporal decision problem becomes

P3 one of choosing the time and consumption goods allocations to maximize k=1 xpk + 2(ha + hb ), subject to the same budget constraints

as before.

The …rst order conditions for this problem are given in the appendix; the

next two Lemmas follow easily:

Lemma 4 When parental time is rival, the …rst and second born do not receive

identical treatment.

Proof: see appendix.

This result is driven by the sequential nature of child rearing, and the assumptions that the investment a child needs di¤ers at each stage.

Lemma 5 Suppose parental time is a public input, so taw2 = tbw2 = tw2 : Then

the …rst and second born do not receive identical treatment.

Proof: see appendix.

The argument above applies here, as well: so long as children require di¤erent

inputs at di¤erent stages, and there is at least one period in which siblings in

di¤erent stages share an input and one in which they do not, then identical

treatment will not be optimal.

13

4.3

Probabilistic Second Birth and Spacing of Children

We assumed above that fertility was deterministic. Suppose instead that the

birth of the second child is probabilistic rather than certain. The household’s

intertemporal objective function is now the expected sum of utilities of the

parents. That is, parents maximize intertemporal utility knowing that they

have one child in the …rst period, but are uncertain whether they will have a

second child or not. Thus parents who, in the second period, have one child, and

those with two children, will have made identical investments in the …rst period.

In the second period, the uncertainty is resolved, and second-period maternal

care for the …rst-born will depend on the existence of the second child: the …rst

child will enjoy both more maternal care and child quality if the second child

is present. This is consistent with Zajonc (1976), who notes that only children

tend to perform less well than …rst borns.

Our model also predicts that if parents can keep trying to have children in

later periods, since the older child moves more and more towards self-su¢ ciency,

a child born in the third period would receive less attention than if the child

were born in the second period. Price (2008) …nds that the longer the spacing

between siblings the bigger the gap in quality time reported for each child at the

same age. Price speculates that parents divide family resources equally across

children at each point in time out of a sense of fairness. Our model o¤ers a

di¤erent explanation for the same observed phenomenon: Parents spend equal

time with their children due to the public nature of maternal child care; as the

spacing of child births increases the bene…t of maternal child care for the older

child decreases and hence less time is spent with both children.

5

References

Bergstrom, Th. C. and R. C. Cornes (1983) "Independence of Allocative Ef…ciency from Distribution in the Theory of Public Goods," Econometrica 51,

1753-66.

Bergstrom, Th. C. and R. C. Cornes (1981) "Gorman and Musgrave are

Dual: An Antipodean Theorem on Public Goods," Economic Letters 7, 371378.

Black, Sandra E., Paul J. Devereux and Kjell G. Salvanes (2005) "The More

the Merrier? The E¤ect of Family Size and Birth Order on Children’s Education," Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol. 120, no. 2, 669-700.

Conley, Dalton and Rebecca Glauber (2006) "Parental Educational Investment and Children’s Academic Risk - Estimates of the Impact of Sibship Size

and Birth Order from Exogenous Variation in Fertility," Journal of Human Resources, vol. 41, no. 4, 722-737.

Cunha, F. and J. Heckman (2007) "The Technology of Skill Formation",

NBER working paper 12840, http://www.nber.org/papers/w12840.

Ejrnæs, Mette and Claus C. Pörtner (2004) "Birth Order and the Intrahousehold Allocation of Time and Education," Review of Economics and Statistics,

14

vol 86, no. 4, 1008-1019.

Hanushek, Eric A (1992) "The Trade-o¤ between Child Quantity and Quality", Journal of Political Economy, Vol 100, No. 1, pp. 84-117.

Heckman, James J. (2007) "The economics, technology and neuroscience of

human capability formation", NBER working paper 13195.

Huang, F. (2006) "Child Development Production Function", working paper

24-2006, Singapore Management University, School of Economics, https://mercury.smu.edu.sg/rsrchpubupload/

Kantarevic, Jasmin and Stéphane Mechoulan (2006) "Birth Order, Educational Attainment, and Earnings - An Investigation Using the PSID," Journal

of Human Resources, vol. 41, no. 4, 755-777.

Price, Joseph (2008) "Parent-Child Quality Time: Does Birth order Matter?

Journal of Human Resources, vol. 43, no. 1, 240-265.

Ruhm, Christopher J. (1998) “The Economic Consequences of Parental

Leave Mandates: Lessons from Europe,”Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol.112,

no.1, 285-317.

Ruhm, Christopher J. (2000) “Parental Leave and Child Health,” Journal

of Health Economics, vol. 19, 931-960.

Todd, P.E and K.I. Wolpin (2007) "The Production of Cognitive Achievement in Children: Home, School, and Racial Gap Test Scores", Journal of

Human Capital, vol. 1no.1, 91-136.

Waldfogel, Jane (2006) what children need, Harvard University Press.

Willis, Robert J. (1973) “A New Approach to the Economic Theory of Fertility Behavior,” Journal of Political Economy, vol. 81, no. 2, part 2: New

Economic Approaches to Fertility, S14-S64.

Zajonc, R.B. (1976) "Family Con…guration and Intelligence", Science, New

Series, Vol 192, No 4236, pp. 227-236.

6

Appendix A

Unless speci…cally mentioned, the husband spends all his time in employment

in each period, that is thk = 0; k = 1; 2; 3:

With quasi-linear utility, the utility of parents is

15

6.1

3

X

k=1

uwk + uhk

!

+ 2(uaA + ubB )

= [(ww1 n) (1 taw1 ) + wh1 + 2Y (taY 1 )]

+[(ww1 (1 + (1 taw1 )) n) 1 taw2

tbw2 + (1 + )wh1

xa2

+2 O(taw2 ; xa2 ) + v tbY 2 ]

+[ ww1 (1 + (1

taw1 )) 1 +

1

taw2

tbw2

(1

tw3 ) + (1 + )2 wh1

+2 A(taw1 ; taw2 ; xa2 ) + O(tbw3 ; xb3 ) ]

+2A(tbw2 ; tbw3 ; xb3 )

The household’s problem reduces to one of choosing

the sequences of maternal child care and private goods

for each child: {ftawk ; tbwk gk=1;2 ; tbw3 xa2 ; xb3 g The FOCs are:

9

8

@ua

@ua

>

>

2 @ta1 (p 1) + 2 @taA

=

<

@

w1

Y1

=0

=

(ww1 n) + ww1 (1 (taw2 + tbw2 )

>

>

@taw1

;

:

b

b

a

+ ww1 (1 + (1 (tw2 + tw2 ))(1 tw3 )

9

8

@ua

@ua

2 @ta2 + 2 @taA

=

<

@

w2

w2

a

=0

=

(ww1 n) + ww1 (1 tw1 )+

;

:

@taw2

b

a

ww1 (1 + (1 tw1 ))(1 tw3 )

9

8

@ubA

@ub2

>

>

2 @tb (p 1) + 2 @tb

=

<

@

w2

Y2

a

=0

=

(ww1 n) + ww1 (1 tw1 )+

>

>

@tbw2

;

:

a

b

ww1 (1 + (1 tw1 ))(1 tw3 )

(

)

@ub

@ub

@

2 @tb 3 + 2 @tbA

=

=0

w3

w3

@tbw3

ww1 (1 + (1 taw1 )) (1 + (1 (taw2 + tbw2 )))

@

@ua2

@uaA

=

2

1

+

2

=0

@xa2

@xa2

@xa2

@

@ub3

@ubA

=

2

1

+

2

=0

@xb3

@xb3

@xb3

Proof of Lemma 1:

by comparison of …rst and third …rst order conditions above.

16

xb3

6.2

Proof of Lemma 2:

If there are full economies of scope for maternal child care, then the decision

problem above is modi…ed as follows:

i) the sum (taw2 + tbw2 ) is replaced everywhere in the decision problem, and

its solution, with the single term tw2 ;

ii) the super-script j = a; b is dropped from the second period maternal child

care terms; and

iii) the second and third …rst order conditions above are replaced by the

single condition

8

>

>

<

@

=

>

@tw2

>

:

@ub

@ua

(ww1

2

+ @tb 2 (p 1)

2 @tw2

Y2

n) + ww1 (1 taw1 ) + ww1 (1 + (1

+2

@ua

A

@tw2

+

@ubA

@tw2

taw1 ))(1

tbw3 )

9

>

>

=

>

>

;

Inspection of the FOC’s shows that

(i) the opportunity cost of parental time is equal to ww1 n in periods 1

and 2. Since in the second period the older child also bene…ts from this care,

the marginal bene…t of maternal child care for the younger child must be lower

in the second period than in the …rst. Given concavity, this means higher

maternal child care in period 2 than in period 1.

(ii) In the …nal two periods parents choose both time and consumption goods

for the older child in each period. Since the younger child needs full time

supervision in the second period, and there is no younger child in the third

period, the opportunity cost of parental time is higher in the third period than

in the second. This implies that the marginal bene…t of parental time in the

third period is higher than that in the second. If tbw3 < tw2 , parents have more

disposable income to devote to consumption goods in the …nal period than in

the middle period, so can divert more private goods towards the child in the

2

O

@O

@O

former period. With @x@j @t

0 and tbw3 < tw2 , if xa2 = xb3 , then @x

j

b

@ta :

k

3

wk

2

Then satisfaction of the …rst order conditions for the older child’s consumption

goods requires xb3 xa2 :

6.3

Proof of Proposition 1: Economies of scope for mother

Suppose taw1 = tw2 = tbw3 and xa2 = xb3 are equilibrium choices. Then all FOCs

must hold with equality. However, comparing @t@a with @t@w2 ; the opportunity

w1

cost of maternal time would be the same, but there are more bene…ts of maternal

time in period 2. Hence we have a contradiction.

Now consider the following experiment. Retain xa2 = xb3 , and suppose

a

tw1 = tw2 at the value which satis…es the FOC for tw2 . Then the partial

wrt taw1 <0 (since the marginal bene…t in the …rst period is less than in the

second).. Notice that lowering taw1 will raise the positive terms in the partial

for that variable, without a¤ecting the negative terms, moving that closer to 0.

On the other hand, this change will decrease the absolute value of the negative

17

terms in the partial with respect to tw2 , reducing that partial, while having an

@ua

A

ambiguous e¤ect on the @tw2

term. This partial can still be equal to zero if

this latter term in increasing in taw1 :

6.4

Proof of Proposition 2: mother’s time is rival

Consider the original problem, and the original six FOC’s.

i) Suppose children receive identical treatment, so taw1 = tbw2 ; taw2 = tbw3 and

a

x2 = xb3 are equilibrium choices, satisfying all FOC’s above. Then the bene…ts

of maternal time are equal in the partials @t@a with @t@b ; while the opportunity

w1

w2

cost of maternal time is lower for taw1 than it is for tbw2 : Hence taw1 = tbw2 cannot

be part of the solution.

ii) Suppose the grown child’s earning potential depends only on …rst period

maternal time, so

=

@ubA

@xb3

=

@ua

A

@ta

w2

=

@ubA

@tbw3

= 0:

a) Is

tbw2 and taw1 are symmetric and

a

> t w1

the opportunity cost of maternal

time in period 1 must be less than that in period 2. Since a young child’s

utility is increasing in parental time, tbw2 > taw1 implies that the marginal

bene…t of maternal time for the …rst born must also be less than that of the

second born if the FOC’s are to hold. However, this requires tbw2 < taw1 so we

have a contradiction.

Thus we have taw1 > tbw2

b) Is tbw3 > taw2 possible? Comparing the FOC’s for these two variables, For

maternal time in the second stage of each child, taw2 is likely to be greater than

tbw3 ; because the cost of alternative child care in the second period is likely to

cause a lower opportunity cost of second period maternal time than the impact

of second-period maternal time has on the opportunity cost of third-period

maternal time. Thus bene…ts are the same but opportunity cost is higher in the

third period and so tbw3 < taw2 : This would also imply a lower child consumption

of the second born than the …rst born and hence a lower utility of the second

born child than the …rst born in his second period of life.

@ 2 ua

iii) Suppose @ta @tAa > 0; this would not change the prediction so long as

w2

w1

child care has a bigger impact on the opportunity cost than wage growth through

maternal human capital investment in the earlier periods.

..

tbw2

6.5

tbw2

@ua

A

@xa

2

> taw1 possible? The FOCs for

implies tbw2 + taw2 > taw1 : This implies

Proof of Proposition 3

Introduce income e¤ect, switch o¤ human capital investment character of parenting

18

@

@taw1

=

8

>

<

@ua

(Y (taY 1 )) xp1 + 2) @ta1 (p 1)

Y1

(ww1 n) + ww1 (1 tw2 )

a

(Y (tY 1 ))

+ ww1 (1 + (1 tw2 ))(1 tbw3 )

(

>

:

8

>

<

0

@ub

@ua

9

>

=

>

;

=0

2

+ @tb 1 (p 1)

O(tw2 ; xa2 ) + Y (tbY 2 ) xp2 + 2 @tw2

Y2

(ww1 n) + ww1 (1 tw1 )

a

b

O(tw2 ; x2 ) + Y (tY 2 )

+ ww1 (1 + (1 tw1 ))(1 tbw3 )

)

@ub2

0

O(tbw3 ; xb3 ) xp3 + 2 @tw3

=0

O(tbw3 ; xb3 ) [ww1 (1 + (1 tw1 )) (1 + (1 tw2 ))]

0

@

@tw2

=

@

@tbw3

=

@

@xa2

=

0

O(tw2 ; xa2 ) + Y (tbY 2 ) xp2 + 2

@

@xb3

=

0

O(tbw3 ; xb3 ) xp3 + 2

>

:

(

@ua2

@xa2

@ub2

@xb3

O(tbw3 ; xb3 ) = 0

2

3

O(tbw3 ; xb3 ) : In order for both FOCs to hold, we

O(tw2 ; xa2 ) + Y (tbY 2 ) >

0

0

must have

O(tw2 ; xa2 ) + Y (tbY 2 ) xp2 + 2 >

O(tbw3 ; xb3 ) xp3 + 2 ; but

since () is strictly concave 0 O(tw2 ; xa2 ) + Y (tbY 2 ) < 0 O(tbw3 ; xb3 ) and

through human capital accumulation of the parents and the fact that there are

no child care costs in period 3, xp2 < xp3 : So we have a contradiction.

6.5.1

Cunha-Heckman variation:

First order conditions are

@

@taw1

@

@taw2

@

@tbw2

@

@tbw3

=

=

=

=

8

<

:

8

<

:

8

<

:

(

2

2

9

1

[ (taw1 ) + (1

)(taw2 xa2 ) ] 1 (taw1 ) 1 =

=0

(ww1 n) + ww1 (1 (taw2 + tbw2 )

;

b

b

a

+ ww1 (1 + (1 (tw2 + tw2 ))(1 tw3 )

1

)(taw2 xa2 ) ] 1 (1

) xa2 (taw2 xa2 )

(ww1 n) + ww1 (1 taw1 )

+ ww1 (1 + (1 taw1 ))(1 tbw3 )

9

1

2

[ (tbw2 ) + (1

)(tbw3 xb3 ) ] 1 (tbw2 ) 1 =

=0

(ww1 n) + ww1 (1 taw1 )

;

+ ww1 (1 + (1 taw1 ))(1 tbw3 )

2

[ (taw1 ) + (1

1

[ (tbw2 ) + (1

)(tbw3 xb3 ) ] 1 (1

ww1 (1 + (1 tw1 )) (1 + (1

19

>

;

O(tw2 ; xa2 ) + Y (tbY 2 ) = 0

Suppose taw1 = tw2 = tbw3 and xa2 = xb3 are equilibrium choices, then all FOCs

@

must hold with equality. However comparing @x@ a with @x

b we can see that

6.6

9

>

=

) xb3 (tbw3 xb3 )

(taw2 + tbw2 )))

1

9

=

;

1

)

=0

=0

@

@xa2

@

@xb3

6.7

=

=

2

[ (taw1 ) + (1

)(taw2 xa2 ) ]

1

1

(1

) taw2 (taw2 xa2 2 )

2

[ (tbw2 ) + (1

)(tbw3 xb3 ) ]

1

1

(1

) tbw3 (tbw3 xb3 )

1

1

1=0

1=0

Proof of Lemma 4: Use the …nal FOC (for xb3 ) to simplify the third (tbw3 ), yielding

tbw3

=

xb3

ww1 (1 + (1

taw1 ))(1 + (1

(taw2 + tbw2 ))

(13)

Then do the same for the fourth and second:

taw2

=

xa2

ww1 (1 + (1

taw1 ))(1 + (1 + (1

tbw3 )))

n

(14)

By inspection, the RHS of the two equations are not (in general) equal - will

only be equal for particular combinations of ( ; n).

6.8

Proof of Lemma 5:

If there are full economies of scope for maternal child care, then the decision

problem above is modi…ed as follows:

i) the sum (taw2 + tbw2 ) is replaced everywhere in the decision problem, and

its solution, with the single term tw2 ;

ii) the super-script j = a; b is dropped from the second period maternal child

care terms; and

iii) the second and third …rst order conditions above are replaced by the

single condition

8

>

>

>

<

@

=

>

@tw2

>

>

:

2

f[ (taw1 ) + (1

)(tw2 xa2 ) ]

1

1

(1

1

) xa2 (tw2 xa2 )

+[ (tw2 ) + (1

)(tw3 xb3 ) ] 1 (tw2 )

(ww1 n) + ww1 (1 taw1 )

+ ww1 (1 + (1 taw1 ))(1 tbw3 )

Given this substitution, use the technique above.

20

1

g

1

9

>

>

>

=

>

>

>

;

=0