In‡ation-targeting (IT) and Price-level-path Targeting Considerations

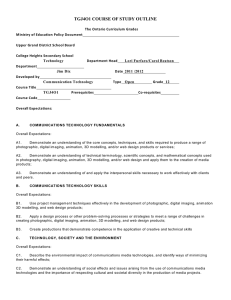

advertisement