FTA Trade Policy in the Presence of Foreign Lobbying Andrey Stoyanov

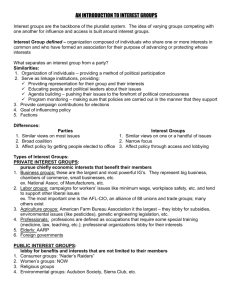

advertisement