Prostate Cancer: A New Brunswick Tale* Peter Sephton School of Business

advertisement

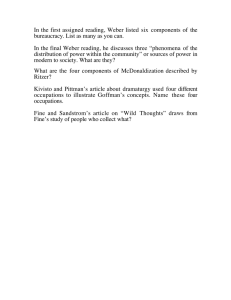

Prostate Cancer: A New Brunswick Tale* Peter Sephton School of Business Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario K7L 3N6 Psephton@business.queensu.ca 613 533 3013 613 533 6589 * VOICE FAX This work is based in part on data provided by the New Brunswick Department of Health and Wellness. The interpretation and conclusions contained herein do not necessarily represent those of the Government of New Brunswick or the New Brunswick Department of Health and Wellness. I thank seminar participants at the Radiation Oncology Research Group at the Kingston General Hospital and Patti Groome and Julian Barling for very helpful comments. Financial assistance from the Canadian Cancer Society Regional Research Development Program and the Dean’s Research Fund is gratefully acknowledged. Abstract From 1988 until 1997 there were 947 deaths from prostate cancer in New Brunswick and 4382 new cases diagnosed. This paper provides a descriptive view of the disease in New Brunswick and examines i) whether the actual number of deaths was different from what could have been expected for each health region, and ii) whether there was a link between occupation and death by prostate cancer. The results suggest that two health regions, and New Brunswick as a whole, experienced more deaths than expected. They also indicate there were occupations in which the number of prostate cancer deaths was significantly different from their expected values. 2 I Introduction From 1988 until 1997, 28 percent of all male deaths in New Brunswick were due to cancer. Of these 8540 deaths, 2997 were caused by lung cancer, with 947 attributed to prostate cancer. During this period there were 4382 new prostate cancer cases diagnosed, the vast majority in men aged 55-74. Treatment regimens depend on a number of factors including age, life expectancy, stage of tumour, and the individual’s preferences over palliative care rather than attempted curation. Options include radiation, surgery, chemotherapy, watchful waiting, or combinations thereof, all of which impose direct and indirect costs on those affected. The purpose of this note is to provide a descriptive view of mortality related to the disease in New Brunswick. Given mortality rates, did New Brunswick experience more deaths than could have been expected? What was the regional distribution of mortality, and what was the distribution by age at death? Is it true that the majority of prostate cancer deaths occur in the elderly? While some researchers attribute prostate cancer to genetic predisposition1, there are other factors such as diet, sexual history, and occupation that may play a role. Was there a link between prostate cancer mortality and occupation in New Brunswick? This latter question is of particular interest given that occupations with exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons - such as farming, construction, and others – have Much of the literature confuses absolute risk: the chance of developing the disease over a particular time period, with relative risk: the ratio of the absolute risk of those containing a certain risk factor to the absolute risk of those without the risk factor. Having a first line relative (brother, father) with prostate cancer is thought to double relative risk. Having two first line relatives diagnosed with prostate cancer quadruples relative risk. Persons of colour have a higher absolute risk than Caucasians. See Gallagher and Fleshner (1998) and Vetrosky and White (1998) for more on the clinical perspectives of the disease, and Dupont and Plummer (1996) on the differences between absolute and relative risk. 1 3 been identified in previous studies as having a higher incidence of the disease.2 As Gallagher and Fleshner (1998) argue, even if there are occupations in which incidence is higher than the norm, the implementation of preventative measures would face a number of challenges, particularly given that the etiology of the disease is unknown. This notwithstanding, it would be helpful for the authorities to understand whether there are specific needs for prostate cancer related services in certain areas of the province. For example, if farmers experienced a higher than expected mortality rate, the government might be expected to provide enhanced services in rural areas to accommodate the needs of the farming community.3 Failing this, the authorities may want to encourage physicians to follow certain patient groups more closely than others, with perhaps a more thorough screening program or protocol than offered to the general population. All have implications over resource allocation.4 II Age and Regional Patterns Vital Statistics data from the Department of Health and Wellness was used in the present analysis.5 It covered all male deaths in New Brunswick from 1988 until the end of 1997. Information on the health region of the deceased, their occupation, date of birth, and cause of death was available. During this period there were over 30,000 male deaths, 8540 the result of See Aronson et al (1996) and Seidler et al (1998) for evidence that exposure to diesel fuel or fumes may be associated with the development of prostate cancer. 3 This presumes that the higher than expected mortality rate is associated with a higher incidence of prostate cancer in farmers, which is outside the scope of the present analysis, and may not be the case. 4 Krahn et al (1999) estimate that the costs of PSA screening programs for all eligible men in Canada could be as high as $412 million by 2005. 5 I thank Chris Heissner and John Boyne for providing this data. 2 4 cancer. There were 947 deaths in which prostate cancer was cited as the cause of death in the vital statistics records. A cursory search of the term “prostate cancer” in internet search engines provides thousands of hits. Public awareness has risen substantially over the past decade, partly as a result of a number of public figures admitting they had the disease. Much of the literature appears to suggest that the majority of prostate cancers are slow-growing and that in all but a small number of cases, a diagnosis of prostate cancer, if made early enough, allows one to effectively treat the disease. The survival rate is relatively high, suggesting that those who do die as a result of prostate cancer are relatively old. Was this the case in New Brunswick? Table 1 contains an agedistribution of deaths from prostate cancer from 1989 until 1997.6 Of the 859 deaths, over 80 percent occurred in patients over 70 years of age. Nearly half of all deaths were in males over 80. What of those individuals who were diagnosed with prostate cancer? Did a majority die from prostate cancer, or was there some other cause of death? Table 2 indicates that 39 percent of those who had been diagnosed with prostate cancer actually died as a result of the disease. A majority died from other causes. These statistics appear to validate the conventional wisdom: over 80 percent of prostate cancer deaths occurred in those aged 70 and over, with nearly half of all deaths occurring at 80 years of age and over. Men Subsequent analyses examine the period from 1989 until 1997. This is because a consistent measure of the male New Brunswick population by health regions was available only back to 1989. 6 5 diagnosed with prostate cancer were more likely to have died as a result of something other than the disease.7 New Brunswick is divided into a number of different health regions. Figure 1 describes the geographic areas associated with each region. From a health policy standpoint, it is interesting to determine whether the actual number of deaths within each region was as might have been expected. Were there “pockets” of prostate cancer, or were there regions in which the number of deaths from prostate cancer was lower than expected? If differences emerge, the Department of Health and Wellness might want to look at those regions to determine if there are structural differences in the management of the disease. For example, differences in clinical practice across the regions or in access to capital-intensive facilities (such as radiological suites not available in each health region) may affect mortality. While prostate cancer mortality appears to have fallen in the late 1990s, Perron et al (2002) suggest that this cannot be attributed to PSA (prostate specific antigen) screening programs, so there may be other factors the Department of Health and Wellness can identify as having a protective influence. Figure 2 presents a regional breakdown of the number of deaths along with the number that would have been expected to occur given the male population within the health region and the mortality rates associated with prostate cancer over this period.8 For the province as a whole there was a statistically significant difference between actual and expected mortality, with more deaths than expected. Health Regions 1 and 6 contributed to this It is worth noting that these results depend critically on the accuracy of the reporting mechanisms in place. If vital statistics data was not collected and coded properly, or if there were variations across regions in the manner in which reports were constructed, then the findings reported herein may not be truly reflective of the disease in New Brunswick. 8 The expected number of deaths is constructed using age-specific mortality rates, standardized to the New Brunswick male population. Age-specific mortality rates were obtained from Health Canada (http://cythera.ic.gc.ca/dsol/cancer/d_age_e.html). 7 6 finding. This suggests the Department of Health and Wellness might benefit from identifying how these two Regions differ from the rest of the province, either in terms of the characteristics of the underlying population (eg., smoking prevalence) or in clinical practice and treatment regimens. III Occupational Factors A number of studies have found evidence supporting an association between occupation and prostate cancer. Exposure to diesel fuel or fumes has been linked to prostate cancer. Farmers and agricultural workers, airline pilots and some chemical workers have experienced higher than expected incidence and mortality rates. Was there a link between occupation and death from prostate cancer in New Brunswick? Vital statistics death records include the occupation of the deceased. To the extent that this information correctly identifies the occupation of the individual (many people work in several different industries over their working lives), it may be possible to determine whether there were more deaths than expected by occupation. To calculate the expected number of deaths, data from the Labour Force Survey was used to establish the distribution of male workers by occupation in New Brunswick. The data from the 1996 Census was used to allocate workers to occupational categories that matched as closely as possible the occupational groupings in the vital statistics records. This provided the proportion of New Brunswick males working in each occupation, which was assumed to represent the distribution of employment over the entire sample period. Given age-specific mortality rates standardized to the New Brunswick population, it is possible to determine the expected number of deaths due to prostate cancer in each region for each occupation. 7 Table 4 presents the actual and expected number of prostate cancer deaths over this nine-year period. For those death records where occupation category was missing or uncoded, the cases were deleted from the analysis (the expected number of deaths also excluded those workers whose occupations were not classified). This reduced the number of actual deaths to 727 cases (there were 132 actual deaths due to prostate cancer where occupational class was not listed or was unclassified). Several results are striking. Occupations in medicine, sales, machining, product fabricating, transportation equipment, and in material handling experienced mortality from prostate cancer as was expected. Many occupations had substantially fewer deaths than expected, notably those in management, the natural and social sciences, teaching, clerical work, services, processing, and artistic fields. Evidence supportive of previous studies into occupational factors and prostate cancer mortality is reported here, with farmers, fishers, foresters, those in mining and construction, and religion facing higher mortality than expected. Table 5 presents Standardized Mortality Ratios and the associated probability values, and demonstrates that these results are statistically significant. The occupations associated with a higher than expected number of deaths are very similar to those identified through case-referent studies and the analysis of more finely refined patient-level data, such as Aronson et al (1996) and Seidler et al (1998). The empirics support the view that certain occupations and prostate cancer mortality – either higher or lower than expected - were associated in New Brunswick during this period. 8 IV Final Remarks The purpose of this note was to provide a descriptive view of prostate cancer mortality in New Brunswick. Nearly three percent of all male deaths during this period were due to prostate cancer, with most occurring in the population aged 70 and over. For those who had been diagnosed with prostate cancer and subsequently died, the vast majority died from something other than prostate cancer. Vital statistics data and information on employment in the province were used to construct estimates of the expected number of deaths from prostate cancer by region and by occupation. For the province as a whole, there were more deaths than expected, mainly in Health Regions 1 and 6. This suggests the Department of Health and Wellness might benefit from determining how these Health Regions differ from the rest of the province, either in the clinical management of the disease or in the underlying characteristics of the population. Support for an association between occupation and death by prostate cancer was found for several job categories. Some occupations experienced fewer deaths than expected. Farmers, foresters, construction workers, and miners experienced more deaths than expected. Given that employment in these areas is high in New Brunswick, there are important implications for health care resource management in the province. In addition, to the extent that farmers, foresters, construction workers and miners have relatively little control over their work environments than workers in other occupations, these findings argue for greater emphasis on workplace safety and an enhanced protective role for governmental agencies. 9 Health policymakers should be interested in the empirical results. The age distribution of mortality appears to indicate that existing protocols offer an effective approach to disease management. There appears to be evidence that Regions 1 and 6 experienced a larger number of deaths than could have been expected, and suggests there may be differences in the underlying characteristics of the population or in clinical practice that distinguish these regions from the rest of the province. The appearance of an association between death from prostate cancer and employment in certain industries requires additional study to determine both the exact transmission mechanism as well as protective measures which can reduce exposure to carcinogens. Physicians might be expected to provide additional screening to men working in occupations identified as being high risk. Further study in this area should focus on patient-level data to determine whether there are unique associations between occupation, location, and even socio-economic factors that contribute to prostate cancer mortality in New Brunswick. 10 References Aronson, K., J. Siemiatycki, R. Dewar, and M. Gerin, (1996), “Occupational Risk Factors for Prostate Cancer: Results from a Case-Control Study in Montreal”, American Journal of Epidemiology 143, 363-373. Dupont, W., and W. Plummer (1996), “Understanding the Relationship Between Relative and Absolute Risk”. Cancer 77, 2193-2199. Gallagher, R., and N. Fleshner (1998), “Prostate Cancer: 3. Individual Risk Factors”, Canadian Medical Association Journal 159 (7), 807-813. Krahn, M., Coombs, A., and I. Levy (1999), “Current and Projected Annual Direct Costs of Screening Asymptomatic Men for Prostate Cancer Using Prostate-Specific Antigen”, Canadian Medical Association Journal 160 (1), 49-57. Perron, L., L. Moore, I. Bairati, P-M. Bernard, and F. Meyer (2002), “PSA Screening and Prostate Cancer Mortality”, Canadian Medical Association Journal 166 (5), 586-591. Seidler, A., Heiskel, H., R. Bickeboller, and G. Elsner (1998), “Association Between Diesel Exposure at Work and Prostate Cancer”, Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment, and Health 24(6), 486-494. Vetrosky, D., and G. White (1998), “Prostate Cancer: Clinical Perspectives”, AAOHN Journal, 46 (9), 434-440. 11 Table 1: Actual Mortality by Age Group, 1989-1997 Age Groups Number % 40-49 8/859 1 50-59 21/859 2.5 60-69 116/859 13.5 70-79 300/859 35 80+ 414/859 48 12 Table 2: Of Those Who Were Diagnosed with Prostate Cancer and Died in New Brunswick: Underlying Cause of Death ICD9 185 410 436 486 496 1539 1629 1991 2500 3310 4140 4149 4275 4280 Description Percentage % Malignant neoplasm of prostate Acute myocardial infarction Acute, but ill-defined, cerebrovascular disease Pneumonia, organism unspecified Chronic airway obstruction, not elsewhere classify Colon, unspecified Bronchus and lung, unspecified Malignant neoplasm without specification of site Diabetes mellitus Other cerebral degenerations Coronary atherosclerosis Chronic ischemic heart disease, unspecified Cardiac arrest Heart failure 39 6 4 1 5 1 4 2 2 1 2 5 3 1 Subtotal 76 Other 24 Total 100 ICD9 refers to the 9 th edition of the International Classification of Diseases coding system. 13 Figure 1: New Brunswick Health Regions 14 Figure 2: Actual and Expected Prostate Cancer Deaths Actual and Expected Prostate Cancer Deaths 300 250 200 Actual 150 Expected 100 50 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Health Region Table 3: Standardized Mortality Ratios with Probability Values Health Region Standardized Mortality Ratio Probability Value 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1.26 0.97 0.98 0.96 0.95 1.25 1.12 0 0.67 0.76 0.80 0.76 0.02 0.40 Total 1.08 0.02 Note: The Standardized Mortality Ratio is calculated as the ratio of the actual to the expected number of deaths. Probability values associated with a test that examines null hypothesis that the expected values equal the actual value. There were 859 deaths due to prostate cancer from 1989 to 1997. 15 Table 4: Actual vs Expected Deaths by Occupation Occupation Managerial, administrative and related occupations Proportion of Male Employment (%) Actual Expected 12.05 60 95 Occupations in natural sciences, engineering and mathematics 5.95 16 47 Occupations in social sciences and related fields 1.67 4 13 0.6 11 5 3.01 14 24 Occupations in medicine and health 1.7 10 13 Artistic, literary, recreational and related occupations 1.6 1 13 Clerical and related occupations 5.23 26 41 Sales occupations 7.92 51 62 12.02 55 95 3.83 90 30 2.4 33 19 Forestry and logging occupations 2.99 41 24 Mining and quarrying including oil and gas field occupations 0.67 10 5 Processing occupations 5.65 23 44 Machining and related occupations 2.81 16 22 Product fabricating, assembling and repairing occupations 6.66 58 52 Construction trades and occupations 9.38 126 74 Transport equipment operating occupations 6.59 48 52 Material handling and related occupations 1.92 17 15 Other crafts and equipment operating occupations 5.35 17 42 Occupations in religion Teaching and related occupations Service occupations Farming, horticultural and animal husbandry occupations Fishing, trapping and related occupations Note: There were 859 deaths due to prostate cancer from 1989 to 1997. Of those, 132 had occupation classes that were not listed or listed as unclassified. These observations were dropped from the occupational analysis. 16 Table 5: Standardized Mortality Ratios with Probability Values Occupation Managerial, administrative and related occupations Occupations in natural sciences, engineering and mathematics Occupations in social sciences and related fields Occupations in religion Teaching and related occupations Occupations in medicine and health Artistic, literary, recreational and reelated occupations Clerical and related occupations Sales occupations Service occupations Farming, horticultural and animal husbandry occupations Fishing, trapping and related occupations Forestry and logging occupations Mining and quarrying including oil and gas field occupations Processing occupations Machinig and related occupations Product fabricating, assembling and repairing occupations Construction trades and occupations Transport equipment operating occupations Material handling and related occupations Other crafts and equipment operating occupations Standardized Mortality Ratio Probability Value 0.63 0.34 0.31 2.2 0.58 0.77 0.08 0.63 0.82 0.58 3 1.74 1.71 2 0.52 0.73 1.12 1.7 0.92 1.13 0.4 Note: The Standardized Mortality Ratio is constructed as the ratio of the actual number of deaths to the expected number of deaths. Probability values associated with a test that examines null hypothesis that the expected values equal the actual value. There were 859 deaths due to prostate cancer from 1989 to 1997. Of those, 132 had occupation classes that were not listed or listed as unclassified. These observations were dropped from the occupational analysis. 17 0.0001 0 0.004 0.02 0.03 0.41 0 0.01 0.16 0 0 0 0 0.04 0 0.09 0.4 0 0.59 0.58 0