Information, Marijuana and the Youth: evidence from French epidemiological data. Fabrice Etilé INRA-CORELA

advertisement

Information, Marijuana and the Youth:

evidence from French epidemiological data.

Fabrice Etilé

INRA-CORELA

May 23, 2002

Abstract

Using French epidemiological micro-data on the health and the lifestyle

of teenagers in secondary schools, we measure the impact of a number of

information providers on youth marijuana consumption. Information variables are instrumented so as to pick up the pure preventative e¤ects only,

we control for habit formation and use of Heckman-Singer semi-parametric

techniques allows us to control for unobserved heterogeneity, and to characterise the p opulation by latent classes. There are three latent classes,

which represents 58, 23 and 19% of the sample. We use psychological

variables and information on other risky behaviours to show that groups

do not di¤er by their time preferences but rather by their risk aversions.

A general conclusion is that information policies may have heterogeneous

and counterproductive e¤ects. Further, we provide evidences that information a¤ects both the preferences and the risk perceptions, and thus has

perhaps only transient e¤ects.

J.E.L. Classi…cation : C24,D83,I12,I18

Keywords: Marijuana, Alcohol, Information.

Acknowledgement 1 I have bene…tted from discussions with Andrew

Clark, Patrick Peretti-Watel, Pierre Kopp. I thank seminar participants

at OFDT/MILDT, INRA/CORELA, University of Paris 1/TEAM. I gratefully acknowledge research support for this paper from MILDT/INSERM,

University of Paris-1/TEAM and INRA/CORELA. Usual disclaim applies.

1

“They say, and it is nearly true, that this substance does not cause any physical ill;

or at least no grave one; but can one a¢rm that a man incapable of action and …t only

for dreaming is really in good health, even when every part of him functions perfectly?

Now we know human nature su¢ciently well to b e assured that a man who can with a

spoonful of sweetmeat procure for himself incidentally all the treasures of heaven and

of earth will never gain the thousandth part of them by working for them. Can you

imagine to yourself a State of which all the citizens should be hashish drunkards?”

Charles Baudelaire (1860) in “Arti…cial Paradises...On haschish and wine as means

of expanding individuality”

1

Introduction

Within less than a decade, marijuana use has increased dramatically among

French teenagers. By 1993, annual prevalence among 17-year old male was

21%. Six years later, 47% of this gender-age class reported use in the past

year [(13), (5)]. Marijuana use is associated with a number of physical and

psychological damages such as increased risk of airways diseases, changes in

motivation, cognitive impairments, tolerance e¤ects, withdrawal symptoms for

chronic heavy smokers, and perhaps gateway e¤ect [(40), (31), (32), (26), (15),

(47), (45), (50)]. Non-medical use of cannabis does not only generate social costs

(through increasing utilization of medical services for example, [(40), (11), (47),

(45), (33)])1 , it could also give rise to well-being losses for the consumer. This

is the case when she is not perfectly informed of the e¤ects of consumption on

her future preferences (through habit formation and changes in health capital)2 .

Some recent works emphasize the impact of risks perception and social “climat”

on trends in the prevalence of marijuana use in the U.S.A. [(2), (45)]. In light

of this result, information as well as price could be an e¢cient regulatory tool.

Understanding the e¤ects of information on youth marijuana consumption may

allow us to develop preventative strategies to reduce consumption3 .

The French drug regulation agency (MILDT) has designed its policies on the

assumption that information will impact drug consumption e¢ciently. However,

1 Social costs generated by cannabis consumption are qualitatively similar to those of any

illegal drug: accidents, cardio-vascular and cancerous morbidity, tra¢c-related violence. In

France, some rough estimates of these costs shows that they are greatly inferior to those of

le gal drugs [ (33)]. However, they should sharply increase with the ageing of the former users’

population.

2 This is also the case if she is inconsistent i.e. if she does not do what she planned to

do even though her environment remains stable. This kind of behaviour can be rationalized

by assuming non-stable preferences or hyperbolic discounting. It is always possible to tax

addictive products in such a way that hyperbolic discounters choices are those of exponential

discounte rs facing the true market prices. [(24)].

3 Usual variables to regulate addictive consumptions such as excise taxes, spatial, temporal

or age-based selling/consumption restrictions are likely to be useless for cannabis. Sparse

estimates yield negative price elasticities ofdemand for marijuana [(41),(44), (10)]. As price

data are rarely available, previous studies have been interested in the e¤ect of the full price of

marijuana. Most studies …nd that the legal risks are negatively correlated with prevalence [

(37), (49), (48), (44), (16)]. However, the teenagers seem to be less responsive to higher …nes

than young adults [(12), (21)].

2

in reality the diversity of information providers “may limit the e¤ectiveness of

a well-designed policy initiative, as prevention information for adolescents may

appear confused, is likely not to be believed, and is thus ine¢cient”. [(36)]. This

paper therefore adress the following issue: what type of information provision

will be the most e¢cient for a public health campaign aimed at marijuana?

I use a French epidemiological database about health and lifestyles of highschool teenagers, in which information variables are as following : “has had

or followed discussions about drugs within your family, your school, with your

friends and/or in the medias” (several choices allowed). With these variables,

we can neither be more precise about the content of the provided information,

nor can we be more speci…c about the way a youth understand information

and use it to revise their beliefs. Moreover, as we have cross-section data, the

information variables may be endogeneous or determined simultaneously with

consumption. Accordingly, I only identify the e¤ect of information providers

on marijuana annual prevalence among the youth, and the variables are always

instrumented.

Risks perception and responses to information providers may be very heterogeneous [(45)], and we would like to identify those individuals who are sensitive

to public information campaigns. Furthermore, the dynamic of consumption

may vary according to past consumption history and other idiosyncratic factors.

I therefore control for past use and unobservable heterogeneities in our estimates.

This has led me to use the Heckman-Singer semiparametric technique, which

allows to classify individuals in groups (or types/classes) whose risky behaviours

and reactions to information are clearly di¤erentiated. Besides, it should also

be borne in mind that alcohol use is deeply rooted in French customs and recent

research suggest that strong interdependancies between alcohol and marijuana

consumption are of major importance in the design of public policy [??, ??]. In

an attempt to control for the e¤ects of alcohol regulation and to identify more

accurately teenagers’ typical behaviours, I estimate together equations for marijuana participation in the past year, heavy drinking (drunkenness in the data) in

the past year and the age of initiation into cannabis or heavy drinking, and also

use information variables relating to alcohol4 . To anticipate the main result,

I …nd that the population can optimally be described by three latent classes,

which represents respectively 58, 23 and 19% of the sample. These types are

featured by di¤erent propensities to consume alcohol and marijuana, and by

di¤erent reactions to information. These pieces of statistical evidence point to

the importance of accounting for unobservable heterogeneities when evaluating

drug policies.

The paper is laid out as follows. In the following section, we brie‡y review the

4 We were unable to identify the main parameters of the structural model proposed by

DiNardo and Lemieux (2001) for three reasons : (i) there are too few teenagers (only 3.8%)

having smoked marijuana without having been drunk in the past year ; (ii) we work on microdata and not state-level agreggated data ; (iii) we have any regional price variables which

help identify this model. In line with argument (i), we have assumed that contemporaneous

correlations between heavy drinking and marijuana use are captured by the unobservable

heterogeneities.

3

theoretical literature on information and addiction. The third section describe

the data, and emphasize the role of unobservable heterogeneities and career (or

habit formation) e¤ects. Section 4 presents the empirical model and section

5 contains our results. I show that the observed consumption behaviours are

a probabilistic mixture of well de…ned “pure” types. In section 6, I interpret

the results using some additional estimates. I conclude on the e¢ciency of the

current French policy.

2

2.1

Theoretical analysis

Information, rational addiction and the full price of

consumption

In Becker and Murphy’s rational addiction model, the current consumption is

explained by past consumption history, the market prices, and the current and

future costs arising from consumption through anticipated habit formation and

destructions of human capital. The agent chooses to consume a quantity that

equalizes the current marginal utility of consumption and its full price. Due to

a lack of price data, a majority of empirical studies on cannabis highlight other

components of this full price such as : (i) the legal risk (ii) the short and long

term health risks and (iii) the risk of stigmatization. Following Bachman and al.

(1998), Pacula and al. (2001) provides some strong evidences of the e¤ect of risk

perceptions. Using panel data analysis, they …nd that changes in perceptions

and attitudes, which are captured by a qualitative judgement index, contributed

for 50% up to 80% to changes in the US agreggated marijuana consumption by

high school seniors between 1982 and 1998.

Orphanidès and Zervos (1995) gained a new insight into the modelization

of addiction behaviour, by assuming that information is not perfect. If the

risk of addiction is not known with certainty before initiation, informations

about the side e¤ects of recurrent intoxications become of a great importance.

Individuals may be interested in gathering informations about the frequency and

the magnitude of risks. In a recent study, Clark and Etilé (2002) …nd that most

of the past health changes of smokers or other smokers in the same household are

positively correlated with smoking. This may re‡ect the presence of adaptive

behaviors using health changes as information. Last, information modi…es also

the perception of the consumption bene…ts as sketched in Duesenberry (1949).

In harmony with these theoretical and empirical insights, the participation

decision can be formalized very simply. Let Ui be the current well-being of the

agent i, net of any current consumption cost. It is a function of a composite

aggregate y i, the quantity of cannabis consumed, x i, and the level of habit

formation h i. Uncertainty about the taste for a drug experience is summarized

by r~i .We assume that young people cannot access the credit market. The full

price ¦i is a function of the market price p, the past, current and anticipated

career of consumption hi ,and the future costs ci which depends on a risk ~¼ i. If

E(.) is the expectation operator, we observe participation conditionally to the

4

information set when :

¯

©

ª¯

@E fUi(yi ; x i; h i; r~i )g ¯¯

> E ¦i(p; ci(h i; ¼~ i ) ¯x =0

¯

i

@x

xi=0

(1)

Information may impact the probability of participation through changes in

anticipations relating to r~i , ¼~ i , and ci(:). Moreover, in a brilliant ethnographical

study, Howard Becker (1955) showed that information and learning processes

are the catalysts of involvment in drugs, as the drug market is a black market

and the e¤ects of drugs are likely to be unknown a priori and idiosyncratic.

Information may change directly either the full price of the consumption (perception of the risk ~¼ i) or the instantaneous preferences (perception of the taste

parameter ~ri), and it will have an indirect cumulative e¤ect through rational

anticipation of habit formation. In the current paper, I do not study the dynamic of beliefs revision and consumption, as the data set is cross-sectional, but

rather the heterogeneity of the reactions to the contacts with several information providers. For the same reason, I do not control for future consumption,

as required by the rational addiction theory, but only for past consumption

(anticipations are thus adaptive). It is shown in section 6 that information

generally a¤ects participation through changes in full prices and instantaneous

preferences.

2.2

Prevention policies and the heterogeneity of information e¤ects

I investigate neither the information search behaviours of the teenagers 5 nor

the changes in consumers’ attitudes and awareness toward health or addiction.I

focus rather on the preventative e¤ects of information in order to evaluate the

e¢ciency of information-based policies These prevention policies aim on one side

at diminushing the probability of consumption (primary prevention) and, on the

other side, at reducing the health risks generated by consumption (secondary

prevention).

We have some good reasons to think that prevention may have unexpected

e¤ects. Indeed, suppose that an information provider plays the role of a “forecasting center” for a teenager who is not certain of the outcome of a drug

experience. This provider send the following signal: “if you take drugs, it will

bring you a net bene…t x”. The teenager uses this forecast as the virtual outcome of her/his experience if and only if she/he trusts the provider. Hence, this

virtual outcome, weighted by the provider’s credibility, is processed as a virtual

experience and helps forming expectations about the real outcome of the experience. If she/he decides to consume, she/he will compare this latter to x. Then,

if the provider’s forecast has been misleading, she/he will revise her trust in this

5 Information may have been gathered after a search. The ex-ante demand for information

depends on the search cost and the expectation of the e¤ects of information on future decisions

and well-being [(27)]. The more there is uncertainty, the more the consumer nee ds information

to reduce it.

5

provider, whose credibility will fall. The more she/he has experimented drugs,

the lower the credibility of the provider will be if its forecasts are always wrong.

If she/he is bayesian and assuming that the signal is discrete6 , informations that

do not sound credible may have the opposite e¤ect to what was expected 7 .

Preventative information toward teenagers usually underscores only the damages generated by drug consumption (the health risks). But the …rst experiences

are usually the best. If consumers’ anticipations are adaptive and not rational,

the good outcomes of the …rst experiences will shift downwards the anticipated

future costs of consumption. The youths discount also heavily the future costs of

current consumption as their time preferences are more myopic (and time preferences may be shifted endogeneously by drug consumption, see [(7)] and [(43)]).

Further, they may value risk-taking behaviors di¤erently. If the anticipations

of well-being proposed by an information provider are never consistent with the

subjective well-being felt by the teenagers, these latter will rationally choose

to act in opposition to the messages. Juvenile behaviors are often explained

by a will of infringing some taboos, but considering more carefully the way

individuals process information may also help to rationalize these “deviances”.

In the end, unobervables heterogeneities related inter alia to the subjective

discount rate and risk aversion generate interpersonal di¤erences in the perceptions and uses of information. There are also some variations in the way agents

process information, as the gap between the perfect bayesian rationality and the

“practical rationality” (Bourdieu, 1972) implemented by agents is not negligible. In a nutshell, the variables capturing contacts with information providers

may have heterogeneous e¤ects, insofar as we do not observe the beliefs revision

process.

3

3.1

The data

The epidemiological data set INSERM 1993

The current paper exploits French epidemiological data from a 1993’s survey

conducted by the French National Institute of Medical Research (INSERM - unit

n ± 472). The national sample of 12931 teenagers is representative of scholars

enrolled in secondary schools. Those in their …rst two years of secondary school

(about 4000 8 ) did not have to reveal their current drug consumptions. Note also

that (i) going to school before 16 is an obligation in France and (ii) some of the

teenagers in the sample are aged over 21. The analysis exclude these latter, as

they may present speci…c caracteristics (scholars usually achieve their A-levels

6 Like “you ought not to take drugs because you will get into trouble” or “take drugs, it

will be marvelous”.

7 This should not hold anymore if the signal is continuous.

8 About 85% of these 4000 te enagers are aged under 13. As drug-taking behaviours and

school outcomes or drop-outs may be correlated, the remaining 15% and those who left school

after 16 might have had an higher probability of drug use. We can not correct this selection

bias.

6

by 18-year old). Extensive statistics and some notes of methodology may be

found in [(13)]. Some descriptive statistics are also reported in annex A.

The fear of being stigmatized as deviant (cannabis consumption is illegal

in France) or of presenting a bad image of one’s community9 [(29), (1)] and

retrospective questions about the age of initiation and lifetime consumption

can yield measurement errors. However, there are few abnormal answers and

few missing values for the variables describing cannabis or alcohol consumption

(between 4 and 10% for alcohol, and less than 6% for cannabis), which suggests

that the teenagers answered sincerely.

3.2

Cannabis consumption and heavy drinking: some evidences

Grouped count variables give information about the consumptions of several

drugs: cannabis, glue/solvent, pharmaceutical drugs, heroin, cocain, hallucinogens or amphetamins consumed up to 2 times, between 3 and 9 times or more

than 10 times in the life and the last 12 months. Frequencies of participation

are very low, except for cannabis: 85% of the youths had never smoked cannabis

in 1993. 9% had done it between 1 and 9 times, and 6% more than 10 times 10 .

It is not possible to distinguish in the data chronic users from occasional ones.

Moreover, youths may likely underestimate their consumption in order not to

be stigmatized as addicts. I will thus focus on the participation decision.

By using the age of initiation and the age of the individual at time of the

survey, we can bound the duration since initiation in a two-years interval11 . 83%

of the teenagers who had been initiated since more than one year took drugs

during the last 12 month.

The distribution of consumption in the past year, as a function of a proxy for

time elapsed since initiation (age-age of initiation) indicates that there are two

groups: on one hand regular users and on the other hand quitters and casual

users (cf. graphic 1). The proportion of regular users (more than ten times

during the last 12 months) seems to be positively correlated with duration since

…rst use. This stylized fact gives rise to two interpretations.

First, duration since initiation could be a proxy for habit formation e¤ects

(cf. section 2), if we assume that use has been continuous since initiation. We

ought to distinguish regular smokers from the youths having had few experiences

since their initiation. The trend e¤ects generated by habit formation will di¤er

9 Ethnical minorities are not yet institutionalized in France and, at the time of the survey,

urban areas were not yet segregated on an ethnical basis but rather on a …nancial one. However, the youth originated from immigration, which lives in poor suburban areas often regard

themselves as elements of a speci…c social group.

1 0 Straight comparison with a similar survey of 1999 shows that in 6 years the abstinence

rate fell by 20%!

1 1 ]age-age of initiation-1;age-age of initiation+1]. Lifetime consumption includes occsions

of consumptions in the past year. We know the year and month of birth, the year and month

of the survey but just the year of initiation into cannabis and heavy drinking.

7

100%

80%

More than 10

60%

Between 3 and 9

1 or 2

40%

Abstinence

20%

0%

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

Time elapsed since initiation

Figure 1: Consumption in the past year vs. mean duration since initiation

in magnitude according to this unobservable heterogeneity. Nevertheless, ceteris

paribus, the earlier the initiation occurs, the higher the participation probability seems to be. However, once again, partially observable heterogeneities or a

third factor (such as the marital status of the parents, family dysfunctions or

poverty) could explain both the precocity of involvment in drugs and the intensity of lifetime consumption. As the sample does not include youths that had

ended up their studies in secondary school, it is not possible to test correctly one

explanation against the other. In some preliminary estimates, we found that,

after controlling for age, the age of initiation is not correlated with the participation probability, by contrast with the duration since initiation. Thereby,

I use this latter as a proxy for habit formation and control for the unobservable heterogeneities generated by the diversity of individual careers. Besides,

epidemiological researchs show that there is a progression in drug involvment,

from cigarette and alcohol to marijuana and sometimes other drugs [??, ??].

Whether this progression is explained by sociological factors (cf. the learning

theory proposed by Howard Becker), pharmacological ones, or a third factor is

beyond the scope of this paper. What really matters is that adolescents are very

unlikely to experiment with marijuana without prior experiences with alcohol.

Consequently, unobservable heterogeneities that explain cannabis consumption

should also carry weight in alcohol participation.

It is well-known that wine drinking is deeply rooted in French culture. Alcohol (and often binge) drinking is not considered as an unhealthy activity as

it is in North America, so that it would be a nonsense from a comprehensive

point of view, to compare alcohol and cannabis consumption1 2 . Accordingly, I

1 2 France

is the country where the average alcohol consumption per inhabitant has decreased

8

have rather considered the life and yearly numbers of heavy drinking occasions

(in the data, drunkenness which is also a grouped count data variable), as well

as the age of initiation to drunkenness. drunkennesses are positively correlated

with usual drinking behaviour.

97.8% of the cannabis-initiated youths had still drunk alcohol and 89.2% had

still been drunk. Furthermore, past-year cannabis consumption and drunkenness occasions are highly correlated. Whilst 96% of those who were not drunk

did not smoke cannabis, 70% of those who were drunk more than ten times did

it. The assumption of independance between both variables is rejected by a

2 test1 3 . Otherwise, only 3.8% of the youths took drugs and were not drunk

in the past year14 . These …gures imply that we can not analyze cannabis consumption without accounting for heavy drinking. This reason has led me to

use informations about heavy drinking and the age of …rst alcoholic/mariholic

drunkenness in order to identify the unobservable heterogeneities (cf. section 4).

To be consistent, I use information variables related to alcohol as explanative

variables.

3.3

Information variables

The information variables are labelled as following : “has had or followed discussions about drugs/alcohol within your family/at school/ with your friends/in

the medias” (several choices allowed, 8 variables). Hence, we know the identity

of some information providers but not the content of the informational signal.

We expect a priori that parents talk their children out of taking drugs. But

some adults may be very liberal if, by instance, they are themselves current or

former drug-users. Furthermore, lifetime cannabis use is negatively correlated

with variables that capture the quality of the relationship between the children

and their parents15 . The absence of discussion about drugs within the family

may therefore be correlated with cannabis use through a third factor, namely

family dysfunctions. Many parents begin to talk about drugs with their children

after having found out that she/he takes drugs. Likewise, until 1990/1996 the

ma jority of schools used to set up information-based preventative campaigns

after the police had to intervene against a tra¢c. Note also that young drug

users may be more involved in seeking informations about drugs in the medias.

However, the French teen press has always been quite hostile to drugs.

the most, going from 17.7 litres of pure alcohol in 1961 to 10.7 litres in 1999. However, in

1996, the average consumption in France was 11.2 litres, to be compard to 7.9 in the UK, 6.6

in the U.S.A. and 6.2 in Canada. Note also that a simple glass of alc ohol does not provide

the same rapture as heavy drinking and cannabis smoking do.

ni: n:j 2

)

1 3 The test statistic is: d2 = P P (nij¡

n

ni:n:j

1 4 Note

n

that these youth do not have particular ethnical caracteristics such as being originated from North-Africa or Middle East.

1 5 Thre e questions labelled as follows: “Family life is to your opinion, rather tense (y/n),

pleasant (y/n), to be sought after (y/n)”. And one question about the sujective feeling of

having thoughtful parents: “My parents are interested in what I do/ would be interested if

they had time for/ take too much interest in what I do/have little interest in what I do”.

9

Friends are costless information providers. 78% of cannabis users still talked

about drugs with their friends, whereas it is the case for only 48% of nonusers. But information gathered by observation or cheap-talk, or the will to get

a status among one’s peers can generate herd behaviour [(9), (19), (4)]. The

identi…cation of the e¤ect of peer information requires some instruments in order

to control for the re‡ection e¤ect [(34)]. Where did friends get their information?

If they are themselves consumers, they will tend to justify their consumption to

their friends. Last, some common caracteristics (the socio-economic status of the

parents, the ethnical origin, the living area and a number of other environmental

factors) may explain both the formation of a peer group and the decision of its

member to consume or not.

As information variables are likely to be endogeneous, I instrument them.

3.4

Income, prices and other variables

Occasionnal cannabis users often consume for free as the drug is bought by

those of the peers who are regular smokers[(30), (1)]. The market price may

thus have little e¤ect on the probability of participation. Otherwise, the price

of a “standard” quantity of cannabis is constant since 20 years, whereas weight

and quality of this unit can vary according to the place and the moment of the

transaction (about 15 euros for 2 to 4 grammas16 ). There were no centralized

and regional statistics of drug-related crimes until the early nineties, even though

the enforcement of drug laws varies across the areas of jurisdiction. I just build

from the data an indicator for the avalaibility of cannabis. It is the rate of

young scholars initiated into cannabis and attending school in the same o¢cial

educational area and living in the same kind of area (town or country)1 7 . Due to

network e¤ects and stigmatization, it is less costly to buy and consume cannabis

where there are more users. This variable may be endogeneous as there are not

many observations in some of the geographical cells. The rate of users varies

from 9% up to 18% percent for a population of 188 up to 1395 youngs. There is at

least 24 initiated youths per cell. I build a similar indicator for drunkennesses.

While estimating the empirical model, I have noticed that introducing these

variables meliorate the identi…cation of the heterogeneities. Regional prices of

alcohol are not available. Moreover the administrative (and economic) areas of

residence are not in our data. However, I use in section 6 the price of alcohol

to estimate duration models for the age of cannabis initiation. It is the yearly

price index of alcoholic beverages de‡ated with the consumer price index (base

100 in 1980, INSEE price indices). This index is not quite appropriate as a

representative youth consume more beer and less wine than a representative

French household. Their average shopping basket is also di¤erent.

Few French youths have a job. Hence, their income consists mainly of the

pocket money given by their parents, which is known. Otherwise, I used dum1 6 The

main quality sold in France is the haschisch from Morocco, which is often blended

with para¢na, a kin of haircare powder called henné, and residuals from tyres.

1 7 More precisely, it is the number of the initiated youths who were surveyed before {age of

initiation+1} as we do not know precisely the date of initiation.

10

mies for pubescence (to control for biological changes) and gender.

4

4.1

Empirical modelling

Basic speci…cation

The main dependent variable is CANyr : “Did you consume cannabis during

¤

the last 12 months”. Let YiC

be a latent variable for the past-year cannabis

participation decision of agent i. The observed dependent binary variable is

Y iC , which is equal to 1 if the teenager consumed, and 0 otherwise. Let XiC be

a vector of explanative variables, the probit model reads :

½

¤

0 if YiC

= XiC ¯ C + ~º iC < 0

Y iC =

(2)

¤

1 if YiC

= XiC ¯ C + ~º iC > 0

and its likelihood is :

LC (Y iC jXiC ) = [1 ¡ ©(XiC ¯ C )]1¡Y iC [©(XiC ¯ C )]YiC

(3)

where © is the cumulative of the standard normal law.

4.2

Heterogeneity

We know that unobservable heterogeneities can bias the correlation inferred between past use history (captured by trend variables) or the way information is

processed and consumption. A common antidote to the omission of possibly

unobservable variables is to model the unoberved heterogeneity as individualspeci…c random e¤ects. But inference can be sensitive to the assumed distribution of the unobserved heterogeneities. An alternative way to deal with this

problem, is the semi-parametric estimator of Heckman et Singer (1984).

Assume that the population consists of a possibly unknown number S of

subpopulations (or components/classes/types). Some decision parameters may

vary from one class to another. Hence, the coe¢cients ¯ C of the covariates

vary across the sample according to some distribution, which is supposed to be

discrete. As the component membership is not known, the likelihood of observation i is a mixture of the probability densities of this observation, when sampled

from components s = 1; :::; S. All observations have the same unconditionnal

probability ®s to belong to the latent class s = 1; :::S. . We have therefore to

condition the individual likelihood by ®s . The likelihood of the sample becomes

:

" S

#

N

Y

X

L=

® s LC j s(Y iC jXiC )

(4)

i=1

s=1

where :

LC j s (Y iC jXiC ) = [1 ¡ ©(XiC ¯ C s )]

11

1¡YiC

[©(XiC ¯ C s )]YiC

(5)

Using this …nite mixture model, we can interpret the point masses of the

distribution of the coe¢cients as latent classes. Each class is representative of

a type of consumption behaviour, and a type of reaction to information.

Furthermore, unobservable heterogeneities should not change a lot along

time. We thus have to incorporate other informations about past and current

behaviours of the youths in order to identify more accurately the latent classes.

Otherwise, they would capture the unobservable heterogeneities that are solely

correlated with cannabis use in the past year. To circumvent this problem,

I model cannabis participation together with heavy drinking in the past year

(ALCyr)18 and the age of …rst cannabis use or …rst drunkenness (AGEmin).

Hence, the latent classes that I will …nd out will not just mimic the observed

classi…cation between users and non-users.

As the empirical hazard function of initiation is not monotonous, I assume

that AGEmin follows a loglogistic law (cf. the graphic in annex A). However,

some individuals will never be alcohol or haschisch drunkards, and we should

thus use a split-population duration model [(17)]. We can not identify properly

such a model, insofar as we do not observe youths on the whole period at risk for

initiation (from the age of 10 up to about 30). Note T i min the variable AGEmin,

and ± i min an indicator which values 1 if the teenager has yet been initiated (and

0 by default). XiD is a vector of explanative variables. The likelihood reads for

this model :

LD (T i minjXiD ) = [S(T i min jXiD )]1¡±i min [f (Ti minjXiD )]±i min

(6)

where S et f are respectively the loglogistic survival and density functions.

Last, ALCyr is modelled through a probit speci…cation. The likelihood is :

LA (Y iAjXiA) = [1 ¡ ©(XiA ¯ iA )]

1¡YiA

[©(XiA¯ iA )]YiA

(7)

Conditionning each likelihood by the latent class, we get the following full

likelihood :

8

93

2

N

S

<

=

Y

X

Y

4

L=

®s LD j s(T i minjXiD )

Lj j s (Y ij jXij ) 5

(8)

:

;

i=1

s=1

j= A;C

It is estimated by an E-M algorithm following Dempster and al. (1977).

To …nd out the optimal number of classes, I just compare the …nal likelihood

penalized by an ad hoc function, for the estimates of the model with 2, 3 or 4

classes. All parameters vary between latent classes, so that adding one class may

1 8 We were unable to identify the semiparametric bivariate probit model for cannabis use

and heavy drinking, as one of the alternative (smoking and no heavy drinking) is rarely chosen. Indeed, in the maximisation step of the EM algorithm, we have to estimate equations for

each class, by weighting individual contributions to the overall likelihood with the individual

probability of belonging to the class. The choice smoking/no drinking may thus be undersampled...Hence, we implicitely assume that any contemporaneous correlation between both

decisions is picked up by the mixture distribution of the constant in each equation.

12

be costly and useless 19 . To ensure the reproducibility of the results, I choose

initial values by a two-step procedure 20 . First, I separate the sample in S groups

using a cluster analysis, on the basis of several psychological variables (selfesteem, optimism, suicidal thougts, impatience, inconsistency). These variables

might capture variations in the pure discount rate, that is the capability to

make plans for the future and to follow them (Masson, 1995). In a second

step, I estimate a multinomial logit for the probabilities of belonging to one or

another group resulting from the …rst step. This logit was conditionned by the

explanative variables of the model. Then, starting values for the E-M algorithm

were set at the predicted probabilities of belonging.

4.3

Identi…cation

Following Etilé (2002), I use the socioeconomic status (SES) of both parents to

instrument the information variables. A simple probit analysis shows that father’s SES is not correlated with past year use, whereas mother’s SES generally

is. The instrument set also includes dummies for the number of brothers and

sisters, the marital status of the parents, the geographical localization (educational area and type of area: country/suburbs/center), the ethnicity, and some

diseases (asthma, allergy, physical disability). Using bivariate probit regressions,

I instrument simultaneously informations about alcohol and cannabis obtained

from a same provider. I then introduce the predicted values of the probabilities of having had information in participation equations for drunkenness and

cannabis 21 .

According to the main predictions of the Economic of the Family, family

information should be well instrumented2 2 . This is curiously not the case (cf.

table A2 in annex A). Instrumentation does not solve the problem of contextual and correlated e¤ects2 3 , as parental SES may explain both the composi1 9 There is no test of the optimal number of classes as 0 is at the boundary of parameter

space. Following Baker & Melino (2000), we use the following criterion : ln(L) ¡p ¤ ln(ln(N)

where L is the …nal likelihood, p is the total number of parameters and N is the sample size .

2 0 The iterative Expected-Maximisation algorithm is monotoneously convergent, but it is

possible to reach di¤erent maxima depending on the starting values. I tried several starting

values and …nd that it converges toward the same maximum, at a slower speed than it did

with predetermined starting values.

2 1 Assuming that there is no unobservable heterogeneity, usual methods for dealing with

the endogeneity of information variables use the Heckman’s approach (as advocated by Vella,

1993): the model should be estimated from equations augmented with Mills ratios estimated

from bivariate probit regressions (see for an example , Variyam and al., 1999). I did not

investigate the compatibility of this approach and the Heckman and Singer’s te chnique.

Moreover, in any two-step procedure, the variance of the coe¢cients of the instrumented

variables are biased (Murphy and Topel, 1985). We have not yet corrected for these bias, and

therefore the variances are probably downward biased.

I will try to solve these problems in a future revision of this paper.

2 2 As there is a the trade-o¤ between quality and quantity of children, the preventative e¤ort

should decrease with the number of children and increase with parental socioeconomic status.

2 3 Manski (1995, p.127) gives the following de…nitions of the three hypotheses which can

explain the similarity of behaviours in a group :

1. “endogenous e¤ect, wherein the propensity of an individual to behave in some way varies

with the prevalence of that behavior in the group.”

13

tion of the peer group, the quality of scho ol drug prevention programs and the

propensity to take drugs. I should therefore control for parental SES in our

main equations. However, the Heckman-Singer technique allows to use these

variables as instruments only. The correlations between the instrumented information variables and past-year participation may therefore be interpreted as

the measures of the primary preventative e¤ect of contacts with information

providers. Last, note that identi…cation relies also on the non-linearity of the

probit of instrumentation.

5

Results

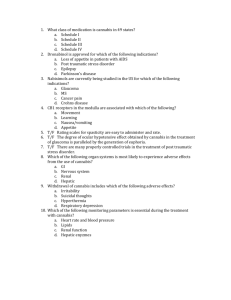

Results are reported in the tables 1 to 3 of annex B. In the probit equations, a

…rst group of variables controls for trend e¤ects (or habit formation) generated

by past uses of alcohol and cannabis. These variables are DURCAN et DURALC, which are built as the age at the time of the survey minus the age at the

time of initiation into cannabis or drunkenness. When the teenager has never

tried cannabis or heavy drinking, these variables are set at 0. When they value

1, I recode them at 0, as initiation may have occured during the last 12 months

(cf. section 3.2). A second group of variables comes to control for gender, age,

puberty and income. Last, a third group helps to identify the e¤ect of the full

price: availability of cannabis on the one hand; informations about cannabis and

alcohol on the other hand. Explanative and dependent variables are described

in tables A1 of annex A.

Explanative variables for the duration equation are dummies for generation

e¤ects, gender, and a dummy which indicates if the natural parents lives still

together2 4 .

5.1

A behavioral typology based on latent classes

Individual heterogeneities are captured by 3 types, which represent respectively

58, 23 and 19% of the population. Given these estimates, we can use Bayes rule

2. “contextual e¤ect, wherein the propensity of an individual to behave in some way varies

with the distribution of background characteristics in the group.”

3. “correlated e¤ect, wherein individuals in the same group tend to behave similarly because

they face similar institutional environments or have similar individual characteristics.”

2 4 For a better inference, AGEmin is recoded as following : AGEmin = age at the time of

the survey- 9 if the teenager has not yet been initiated into c annabis or drunkeness; AGEmin

= (age at the time of the survey + age of initiation)/2 - 9 if the teenager has yet been initiated

and age of initiation is equal to the whole value of the age at the time of the survey; AGEmin

= (age of initiation + 0.5) - 9 if the teenager has yet bee n initiated and this age of initiation

is equal to the whole value of the age at the time of the survey.

Hence, I eliminate from the estimation sample individuals aged under 9. I could have adress

the imprecision of our duration data by using a duration model, in which the second term of

the likelihood, f (Ti min jXiD ), would be replaced by (S(Ti¤ jXiD ) ¡ S(min(Ti¤ + 1; T i )jXiD )),

where Ti¤ is the age of initiation and T i the age at the time of the survey. Preliminary

estimates have shown that this model does not yield di¤erent results and takes much more

time to be estimated than our simpler speci…cation.

14

to calculate for each observation i the probabilities of belonging to classes 1, 2,

or 3:

Pr (i

2 sjY

=

; Y iA ; T i min; X iC ; X iA; X iD )

Pr (Y iC ; Y iA ; T i min ji 2 s; X iC ; X iA ; X iD ) Pr(i 2 s)

(9)

PS

s=1 Pr (Y iC ; Y iA; T i min ji 2 s; X iC ; X iA; X iD ) Pr (i 2 s)

iC

The probability in the numerator is the likelihood of observation i, conditionnal to being of type s. Furthermore, we know the mean caracteristics of an

agent who would belong to one class s. The sample mean ex-post probability

of belonging to the class s for agent i with caracteristic xi = 1 is given by :

X

1

Pr (i 2 sjxi = 1) =

Pr (i 2 sjY iC ; Y iA ; T i min; X iC ; X iA ; X iD )

#fi=x i= 1g

i=xi =1

(10)

Conversely, the sample mean type-conditional probability that x i = 1 is :

1 X Pr (i 2 sjY iC ; Y iA ; T i min; X iC ; X iA; X iD )

Pr(xi = 1ji 2 s) =

xi

(11)

N i

®s

Using other variables of risky behaviours, health status and socioeconomic

caracteristics help to caracterize the behavioral features of each latent class.

Some of the descriptive statistics I have computed for this analysis are presented

in the tables of annex A.

Youths of the …rst type25 are close to the pure type “abstinent”. Actually,

41% of them have still experienced tobacco whereas they are 64% and 80% in

the two other classes. Less than 10% smokes at least one cigarette per day.

Heavy drinking is rare. While 69% had still drinked alcohol, only 10% had still

been drunk, and 2.3% had still used marijuana.

Individuals from classes 2 and 3 di¤er essentially with respect to their drinking behavior. The mean age does not vary across classes (between 16 and 16.5)

but those from the third type drink much more, with a rate of yearly drunkenness higher than 80%, whilst it is only 4.3% in the …rst class and 40.7% in the

second. However, both second and third components have an high proportion

of cannabis users, around 30%. The rate of risky consumptions (more than 10

marijuana uses or drunkennesses during last year) is also the same. But conversely, youths with risky consumption behaviours have a 50% probability of

belonging to class 2, whilst it is only 30% for class 3. Last, the circumstances

surrounding heavy drinking occasions are not the same across these two groups.

Youths who drink more during family celebrations or with friends tend to belong

to the third group. At the opposite, the teenagers who drink more when they

are in a bad mood have an higher probability to belong to the second group.

Thus, individuals who have non-social or dangerous uses of alcohol and marijuana are more likely to be of the second type, which could be caracterized as a

“risky user” type, whereas the third type represents broadly “happy users” 26 .

2 5 In reality, a youth does not belong entirely to one class: this is an abuse of language as

we consider indeed statistical entities not individuals.

2 6 This may re‡ect, of course, an european point of view wherein the lack of social and

15

5.2

Types, time preferences and risk aversion

Do types di¤er with respect to their time preferences and risk aversion? If

it were true, given that these factors are good predictors of risky behaviours,

then probabilities of belonging should also predict these behaviours. Actually,

youths from the second type tend to have more often sexual intercourses without

preservatives and with di¤erent parters. Likewise, the conditional probabilities

to have a sport or a road accident increase with the type. Last, a youth from

the second and the third type get more pocket money (with a mean of about 31

euros/month to be compared to 22 euros for the …rst type), and we know that

absolute risk aversion decrease with wealth. Hence, the second and the third

type should be less risk-adverse.

Preference for the future is said to be positively correlated with human

capital and wealth, and negatively related to the psychological health status and

lifecycle negative shocks [(35), (7)]. There are little di¤erences in the parental

socio-economic status between types. Teenagers whose mother is blue or white

collars have an higher probability of belonging to classe 2 or 3, whereas teenagers

whose mother is at home or father is a worker tend to belong to class 1. School

satisfaction and outcomes are about the same across all classes.

I eventually use several questions bringing on the psychological pro…le and

the lifecycle shocks of the teenager. These variables indicate if she/he is impatient, has lost heart, depressed or able to achieve the tasks she planned to

do (which is a good proxy for dynamically inconsistent behaviours), and the

marital status of her parents. They summarize the capability to make projects

for the future (thus re‡ecting an high preference for the future, (35)) or shocks

on the discount rate. Types 2 and 3 are more impatient and depressed, and

less consistent. But variations of time preferences might be caused by consumption. Being depressed or impatient does not seem to be correlated with the

probability of belonging to classes at odds for consumption. Conversely, having

separated or deceased parents increases this probability. In the end, the link

between types and the time preferences is fuzzy. As emphasized by sociologists

[??], di¤erences in risk aversion play a more important role: in the referential of

the teenage subcultures, risky behaviours often generate bene…ts that one can

not ignore. Failure to take this into account may lead to overstate di¤erences

in the time preferences across agents.

6

6.1

Interpreting the results

Assessing the impact of information providers

At …rst glance, an information provider will have a preventative e¤ect if it

decreases the propensity to consume cannabis. But, as there are unobservable

heterogeneities (cf. section 2.2), the results reveal a sharp distinction in the

time boudaries around drug experiences rather than the level of consumption is seen as the

main symptom of a true addiction. From a sociological point of view, the medical norms for

addiction are not objective, but a cultural product of each society.

16

e¤ect of information providers, according to the group. Then, it might be

thought that individuals use the same pieces of objective informations in many

various ways. According to theory (equation 1 and DiNardo and Lemieux, 2001),

information a¤ects participation probabilities by two channels, which consist of

:

² modifying instantaneous utility (i.e. taste perception). Remember that

trend variables control for any indirect lagged e¤ect through habit formation.

² changing the full prices (i.e. risk perception). Increasing the full price

of one good should decrease participation and induce a change in other

goods’ participation through changes in the relative prices.

Assume that market prices and information have the same e¤ect on the full

price (e.g. a “bad” information about cannabis increases its full price). Then,

knowing the cross and direct price e¤ects, we can show that information e¤ect

through full price is often counterbalanced by variations of instantaneous preferences. Using additional assumptions about the e¤ect of information providers

on the full prices of alcohol and cannabis, it is then worth wondering wether

our information dummies are correlated with participation solely through their

e¤ect on full prices. Teenagers’ preferences are quite unstable, because adolescence is a period of role transition from childhood to adulthood 27 . Therefore,

one may suppose that the more an information provider a¤ects participation

through changes of full prices, the more its e¤ect will last as it means that

perception of the true health risks have been modi…ed. By contrast, the e¤ect

of an information on instantaneous preferences shall vanish quickly. One can

also argue that it is important to keep youths’ preferences “under pressure” as

they are more likely to be in‡uenced by peers during periods of role transition.

But from a …nancial point of view, such a strategy is more expensive than a

“once-for-all” one.

In the next subsection, I attempt to estimate indirectly the signs of the

price e¤ects. I use these results to assess the e¢ciency of public information

providers on the one hand, and private ones on the other hand.

6.2

The e¤ect of full prices

In the absence of cross-sectional prices, I estimate for each class (by using probability weights) a duration model for the age of initiation into cannabis (table

4, annex B). It is quite clear that such a model performs po orly on our data, as

we face sample selection problems 28 . I use the time series of year relative price

indices of alcohol and tobacco to infer the sign of the correlation between prices

2 7 Phenomenological consumer researchs show that compulsive consumption acts are intensi…ed during periods of role transition (see for an e xample Hirschman, 1992).

2 8 As noticed previously, we do not observe teenagers on the whole period where they are at

risk for initiating consumption.

17

Alc. Bev.

19

97

19

94

19

91

19

88

19

85

19

82

19

79

19

76

Tobacco

19

73

Relative price index

19

70

1,6

1,4

1,2

1

0,8

0,6

0,4

0,2

0

Year

Figure 2: Price index of alcoholic beverages and tobacco de‡ated by the consumer price index (source: INSEE)

and the age of initiation (cf. graphic 2). I also control for generation e¤ects,

puberty and gender.

The price e¤ects are strongly positive for the …rst type : age of initiation

increases with prices. Hence, the cross-price e¤ect of alcohol on cannabis participation is negative for class 12 9 . As the e¤ect of income on participation is

null, this implies that heavy drinking and cannabis smoking are hicksian complements. Cross-price e¤ects are negative but somewhat unsigni…cant for types

2 and 3. Goods are likely to be hicksian substitutes for the latter, but complement for the former. Table 5 in annex C show the signs of the marshallian

direct and cross-price e¤ects obtained from our estimates. I use it to predict the

e¤ect of full prices on cannabis and alcohol participation, although the sign of

some price e¤ects is not well determined (as emphasized by the question marks

in the tables).

6.3

School and the medias

Suppose that the medias and school increase the full prices of both alcohol

and cannabis. It is easily seen that the observed and predicted signs of the

cross-price e¤ects of alcohol price on cannabis participation are opposite for

2 9 There

is consumption when the ratio of the relative marginal utilities of cannabis and

heavy drinking is higher than the ratio of relative full prices. If zero consumption has no

speci…c de terminants, this condition is tantamount to x¤ (¼A ; ¼C ; X C (t)) > 0 where x¤ ()

is the latent marshallian demand function (i.e. the solution of the …rst-order optimisation

condition in the absence of Kuhn and Tucker’s multiplicators).

18

the …rst group (Tables 6 and 7). This means that media information about

alcohol a¤ects the instantaneous preferences of these teenagers. However, school

information could also decrease the full price of alcohol and increases cannabis

price. Using arguments developped in section 2, we can eventually state that

either school information about alcohol is not credible or it impacts both youths’

preferences and (anticipation of) full prices. In either case, it may be partially

ine¢cient. Nevertheless, the cumulate e¤ect of school information about alcohol

and cannabis is negative on both alcohol and cannabis participations. Hence,

school informations about drugs and alcohol shall not be delivered separately,

even if evidence are mixed about their e¤ect on full prices and, as a consequence,

perceptions of the true health risks. We can achieve the same conclusion for the

medias.

The second group is more responsive to information. School information

incites globally these teenagers to substitute alcohol and cannabis in favour of

this latter. Moreover, it is not signi…cantly correlated with heavy drinking. If we

interpret our results strictly, we should conclude that this substitution e¤ect is

not a price e¤ect and consequently, that for the second type, school information

is totally ine¢cient. However, if we are less bothered about the signi…cativity of

our results (and ignoring the question marks in the tables), we see that school

information may increase the full prices of both goods. The total e¤ect of school

information about drugs and alcohol is positive. Hence, school information may

have a preventative and lasting e¤ect (through changes of risks perceptions), if

it concerns only cannabis. This result contradicts our …nding for the …rst group.

The medias necessarily a¤ect preferences for cannabis. They have an overall

(perhaps not durable) negative impact on heavy drinking and cannabis use.

Compared to the second group, information has less e¤ect on the behaviours

of the youths from the third group. It turns out that school information could

change the participation probability through full prices if it lowered them (cf.

tables 10 and 11 ). I think that it is unlikely to be case, which means that

this information provider modi…es especially the preferences. It has however a

preventative e¤ect, like the medias, which also induces variations of preferences.

6.4

Friends and the family

Information from friends should decrease the full prices. For the …rst group,

its impact on cannabis participation is slim, probably because youths from this

group have little accointances with drug users. It has also no e¤ect on youths

from the third class. For these two groups, straight comparisons between price

and information e¤ects show that information from friends alters mainly the

preferences. This is not true for the teenagers of the second group. Peer information increases their odds for both heavy drinking and cannabis. This e¤ect

is compatible with a decrease of full prices, although friends may also in‡uence

preferences. Such …ndings are not surprising, as there are more users in the

second class and as the individuals from a same class are likely to match in the

19

same peer groups. What we observe could just be the correlated or context

e¤ects described by Manski (1995).

For the …rst group, family information is not correlated with consumption,

even though this kind of youths has as many discussions within family as other

types do. Perhaps information from the family is not credible. But, we shall

interpret this result carefully, as there are few drug users in the …rst class.

For the second group, there is no doubt that family information has a counterproductive e¤ect (table 9). As emphasized in section 2.2, just arguing that

cannabis is a “bad”, may result in a lost of credibility. However, using table 8,

we see that our results are not compatible with any kind of price e¤ect. A more

traditional interpretation is that the teenagers are often reluctant to do what

their parents expect them to do. This “psychological” will to break taboos could

push them to act in contrast with parental opinions and desires, by changing

their preferences. I have investigated the relationship between class belonging

and qualitative variables capturing family dysfunctions. It is not surprising that

the youths from the second and the third groups are more likely to have relational problems with their parents (little interest of the father as felt by the

youth, family life that looks rather stressing or unpleasant). However, family

information has little e¤ect on the behaviours of the third group.

7

Concluding comments

Using cross-section data about the health and lifestyle of French teenagers, I

investigated the correlations between information and cannabis consumption.

I proposed a latent class probit model that accounts for the heterogeneity in

the coe¢cients of interest. I assumed that this heterogeneity arises because the

true model is a mixture of di¤erent probit models. Results show that there were

in 1993 three latent classes, which represented respectively 58%, 23% and 19%

of the population. The …rst class gathered teenagers that were less prone to

smoke tobacoo, cannabis or drunkenness. They were less risk adverse, because

less involved in risky behaviours. Both other classes contained more consumers

(about 30% each). But the third class was more alcohol-oriented, in the sense

that the propension to heavy drinking is much higher. Moreover, they drunk

during social events (with friends or within family), whereas the youths who

belonged to the second class were more likely to drink alone and when they feel

depressed.

Two general conclusions can be drawn from this study. First, the e¤ect

of public policies is heterogeneous which impede the design of e¢cient general

public policy. By instance, recurrent campaigns at school against drugs and

alcohol would have a preventative e¤ect for the …rst and the third groups (the

participation probability will fall respectively from -0.3% and -52%), but an

incitative one on the second group(+23.5%)3 0 . The “real” e¤ect would be a

3 0 For each group, we can simulate the e¤ect of …nite changes in school informations about

drugs and alcohol, by computing the di¤erences in probability as the value of the two variables

20

decrease of 4.8% in prevalence with unexpected consequences for the youths

who are more likely to belong to the second group. Second, information does

not a¤ect only the full prices of alcohol and drugs (i.e. perceptions of future

health risks) but also the instantaneous preferences of users. Thus, information

at school must be provided every year which may reveal costly.

Information delivered within family may have surprising and unexpected

e¤ects, especially when there are family dysfunctions. Last, peer groups have

an in‡uence on the risks perceptions of individuals from the second groups,

who are more likely to have socially unbounded consumption behaviors. This

suggests that, conversely, targetting peer groups could be an e¢cient strategy

for disseminating information

In addition to …nding evidence of the great heterogeneity of information

e¤ects, we have found that alcohol and cannabis are economic complements for

the major part of the population and merely substitutes for the other. Therefore,

future studies on drugs regulation will have to account for the heterogeneity of

preferences.

References

[1] Aquatias, S., Maillard, I. and Zorman, M. (1999), Faut-il avoir peur du

haschisch? Entre diabolisation et banalisation : les vrais dangers pour

les jeunes, Paris : Syros, coll. Alternatives Sociales, 224 pages.

[2] Bachman, J.G., Johnston, L.D., and O’Malley, P.M. (1998), “Explaining recent increase in students’marijuana use : Impacts of perceived risks and

disapproval, 1976 through 1996”, American Journal of Public Health,

88 (6), 887 - 892.

[3] Baker, M. and Melino, A. (2000), “Duration dependence and nonparametric

heterogeneity: A Monte Carlo study”, Journal of Econometrics, 96,

357-396.

[4] Bala, V. and Goyal, S. (1998), “Learning from Neighbours”, Review of

Economic Studies, 65, 595-621.

[5] Beck, F., Legleye S, and Peretti-Watel, P. (2000), Regards sur la …n de

l’adolescence. Consommations de produits psychoactifs dans l’enquête

ESCAPAD 2000, Paris : OFDT, 220 pages.

[6] Becker, G.S. and Murphy, K.M. (1988), “A Theory of Rational Addiction”,

Journal of Political Economy, 96 (4), 675-700.

[7] Becker, G.S. and Mulligan, C.B. (1997), “On The Endogeneous Determination of Time Preference” , Quaterly Journal of Economics, 112 (3),

729-758.

change from zero to one, holding every other variables constant at their group’s mean values.

Such group representative individuals are pure statistical entities.

21

[8] Becker, H.S. (1955), Outsiders, Paris : Editions A.-M Métailié, 1985, coll.

Observations, 248 pages.

[9] Bikhchandani, S., Hirshleifer, D., and Welch, I. (1992), “A Theory of Fads,

Fashion, Custom, and Cultural Change in informational Cascades ”,

Journal of Political Economy, 100(5), 992-1026

[10] Cameron, L. and Williams, J. (2002), “Alcohol, Cannabis and Cigarettes :

Substitutes or Complements? ”, The Economic Record, 78(240), pp.??)

[11] Chaloupka, F.J. and Laixhutai, A. (1997), “Do Youths Substitute Alcohol and Marijuana? Some Econometric Evidence”, Eastern Economic

Journal, 23 (3), 253-276.

[12] Chaloupka, F.J., Grossman, M. and Tauras, J.A. (1999), “The demand for

cocaine and marijuana by youth”, in The Economic Analysis of Substance Use and Abuse : An integration of Econometric and Behavioral

Economic Research, chap. 5, Chaloupka, F.J., Grossman, M., Bickel,

W.K. et Sa¤er, H. editors, Chicago : The University of Chicago Press.

[13] Choquet, M. and Ledoux, S. (1994), Adolescents, enquête nationale, Paris

: Inserm/La Documentation Française, 346 pages.

[14] Dempster, A.P., Laird N.M. and Rubin, P.B. (1977), “Maximum-Likelihood

from incomplete data via the E-M algortihm”, Journal of the Royal

Statistical Society, B39, 1-38.

[15] DeSimone, J. (1998), “Is Marijuana a Gateway Drug?”, Eastern Economics

Journal, 24 (2), 149 -164.

[16] DiNardo, J. and Lemieux, T. (2001), “Alcohol, Marijuana and American

Youth : The Unintended E¤ects of Government Regulation”, Journal

of Health Economics, 20, 991-1010.

[17] Douglas, S. (1998), “The duration of the smoking habit”, Economic Inquiry, 36, 49-64.

[18] Duesenberry, J.S. (1949), Income, Saving and the Theory of Consumer

Behavior , Cambridge, MA : Harvard University Press.

[19] Ellison, G. and Fudenberg, D. (1995), “Word-of-Mouth Communication

and Social Learning”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 110(1), 93-125.

[20] Etilé, F. (2002), “La prévention du tabagisme des adolescents français”,

forthcoming in the Revue d’Economie Politique.

[21] Farrelly, M.C., Bray, J.W., Zarkin, G.A., Wendling, B.W., Pacula, R.L.

(1999), “The e¤ects of prices and policies on the demand for marijuana

: evidence from the national household surveys on drug abuse”, NBER

Working Paper : 6940, 22 pages.

[22] Festinger, L. (1957), A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance, New-York :

Evanston.

[23] Galland, 0. (2001), “Adolescence, post-adolescence, jeunesse : retour sur

quelques interprétation”, Revue Française de Sociologie, 42 (4), 611-640.

22

[24] Gruber, J. and Köszegi, B. (2001), “Is addiction “rational”? Theory and

evidence”, The Quaterly Journal of Economics, 116 (4), 1261-1303.

[25] Heckman, J. and Singer, B. (1984), “A method for minimizing the impact

of distributional assumptions in econometric models for duration data”,

Econometrica, 52, 271-320.

[26] Henrion, R. (sous la dir.) (1995), Rapport de la Commission de Ré‡exion

sur le Drogue et la Toxicomanie au Ministre des A¤aires Sociales, de

la Santé et de la Ville, Paris : La Documentation Française, 156 pages.

[27] Hirshleifer, J. and Riley, J.G. (1979), “Survey on uncertainty and information”, Journal of Economic Literature, 17.

[28] Hirschman, E.C. (1992), “The Consciousness of addiction: Toward a General Theory of Compulsive Consumption”, Journal of Consumer Research, 19, 155-179.

[29] Hoyt, G.M. and Chaloupka, F.J. (1994), “E¤ect of survey conditions on

self-reported substance use”, Contemporary Economic Policy, 12, 109121.

[30] Ingold, R. and Toussirt, M. (1998), Le cannabis en France, Paris : Anthropos/Economica, coll. Exporation interculturelle et sciences sociales, 192

pages.

[31] Kandel, D.B., Yamaguchi K., and Chen, K. (1992), “Stages of progression

in drug involvement from adolescence to adulthood: Further evidence

for the gateway theory”, Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 53, 447-457.

[32] Kandel, D.B. and Yamaguchi, K. (1993), “From beer to crack: Developmental patterns of involvement in drugs”, American Journal of Public

Health, 83, 851-855.

[33] Kopp, P. and Fenoglio, P. (2000), Le coût social des drogues licites (alcool

et tabac) et illicites en France, Paris : OFDT, 280 pages.

[34] Manski, C.F. (1995), Identi…cation Problems in the Social Sciences, Cambridge, MA : Harvard University Press, 1995, 184 pages..

[35] Masson, A. (1995), “Préférence temporelle discontinue, cycle et horizon de

vie”, in Le Modèle et l’Enquête, L.A. Gérard-Varet et J.C. Passeron

eds., Paris : Editions de l’EHESS, 325-400.

[36] MILDT [1999], “Plan Triennal de Lutte contre la Drogue et de Prévention des Dépendances 1999-2000-2001”, http ://www.drogues.gouv.fr,

« ré‡exions et débats/communiqués de presse ».

[37] Model, K.E. (1993), “The e¤ect of marijuana decriminalization on hospital

emergency room drug episodes : 1975 - 1978 ”, Journal of the American

Statistical Association, 88 (423), 737 - 747.

[38] Mo¤att, P.G. and Peters, S.A. (2000), “Grouped Zero-in‡ated count data

model of coital frequency”, Journal of Population Economics, 13, 205220.

23

[39] Murphy, K.M. and Topel, R.H. (1985), “Estimation and Inference in TwoStep Econometric Models”, Journal of Business and Economic Statistics, 3 (4), 370-379.

[40] Nahas, G. (1976), Haschisch, Cannabis, et Marijuana, le chanvre trompeur,

Paris : Presses Universitaires de France, 434 pages.

[41] Nisbet, C.T. and Vakil, F. (1972), “Some estimates of price and expenditure

elasticities of demand for marijuana among U.C.L.A. students”, The

Review of Economics and Statistics, 54 (4), 473 - 475.

[42] Orphanides, A. and Zervos, D. (1995), “Rational Addiction with Learning

and Regret” , Journal of Political Economy, 103 (4), 739-758.

[43] Orphanidès, A. and Zervos, D. (1998), “Myopia and Addictive Behavior” ,

Economic Journal, 108 (446), 75-91.

[44] Pacula, R.L. (1998b), “Do es increasing the beer tax reduce marijuana consumption?”, Journal of Health Economics, 17 (5), 557 - 586.

[45] Pacula, R.L., Grossman, M., Chaloupka, F.J., O’Malley, P.M., Johnston,

L.D. and Farrelly, M.C. (2001), “Marijuana and Youth” in Risky Behavior among Youths: An Economic Analysis, chap 6., Jonathan Gruber

editor, Chicago : The University of Chicago Press.

[46] Peretti-Watel, P. (2001b), La Société du Risque, Paris : La Découverte,

coll. Repères., 124 pages.

[47] Roques, B. (1999), La dangerosité des drogues , Rapport au Secrétariat

d’Etat à la Santé, Paris : La documentation Française/ Editions Odile

Jacob , 316 pages.

[48] Sa¤er, H. and Chaloupka, F.J. (1995), “The Demand for illicit drugs”,

National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper : 5238, 20 pages.

[49] Thies, C.F. and Register C.A. (1993), “Decriminalization of marijuana and

the demand for alcohol, marijuana and cocaine”, Social Science Journal,

30 (4), 385 - 399.

[50] Van Ours, J. (2001), “Is Cannabis a Stepping-Stone for Cocaine?”, CEPR

Discussion Paper 3116.

[51] Variyam, J.N., Blaylock, J. and Smallwood, D. (1999), “Information, endogeneity and consumer health behavior: application to dietary intakes”,

Applied Economics, 31, 217-226.

[52] Vella, F. (1993), “A Simple Estimator for Simultaneous Models with Censored Endogenous Regressors”, International Economic Review, 34 (2),

441-457.

24

A

Descriptive statitistics

0,18

0,16

0,14

0,12

0,1

0,08

0,06

0,04

0,02

0

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

Empirical hazard of initiation into cannabis or drunkeness

Tables A2: % of good prediction from the bivariate probits for

instrumentation

Information variable

%

Family / drugs

School /drugs

Friends / drugs.

Medias / drugs

Family / alcohol

School / alcohol

Friends / alcohol

Medias / alcohol

58.4%

70.3%

61.6%

66.8%

58.6%

76.3%

75.9%

72.4%

25

Table A1: description of the variables

Variable name

Variable label

CANAN

ALCAN

Sex

Pub.

Age

Inc1000

=1 if initiated into cannabis

=1 if initiated into drunkenness (heavy drinking)

=1 if male

=1 if pubescent

Age

Monthly pocket money (in 1993 FF)/1000

Rate of initiation into cannabis in the same geographical cell

(educationnal area * town/country)

Rate of drunkennesses in the same geographical cell

=0 if not initiated into cannabis

else = (age at time of the survey- min(age of initiation+1;age at time of the survey)

=0 if not initiated into heavy drinking

else = (age at time of the survey- min(age of initiation+1;age at time of the survey)

Has had or followed a discussion about drugs within the family

Has had or followed a discussion about drugs at school

Has had or followed a discussion about drugs with friends

Has had or followed a discussion about drugs in the medias

Has had or followed a discussion about alcohol within the family

Has had or followed a discussion about alcohol at school

Has had or followed a discussion about alcohol with friends

Has had or followed a discussion about alcohol in the medias

RateCan

RateDrunk

DURCAN

DURDRUNK

INFCANfa

INFCANsc

INFCANpe

INFCANmed

INFALCfa

INFALCsc

INFALCpe

INFALCmed

Mean (N=6534)

12.8%

27.9%

47.6%

90.2%

16.17 (se: 1.96)

0.17 (se: 0.46)

0.12 (se: 0.08)

0.23 (se: 0.06)

0.20 (se: 0.72)

0.56 (se: 1.16)

46.8%

29.9%

52.6%

34.4%

49.2%

23.7%

54.9%%

27.6%

In the cell (row=X, column=Y), one reads Pr(XjY).

Sociodemographic

caracteristics

Total

sample

(N=6534)

Type 1

Type 2

Typ e 3

Fath.

farmer

Fath.

Fath.

crafts./ret.worker

Moth.

farmer

Moth.

up.

occ.

Moth.

worker

Moth.

at

home

Inc. 0

Inc. 0100

Inc.

100500

Inc.

500 +

Type 1

Type 2

Type 3

Male

Age

Father farmer

Fath. craftsman or

retailer

Fath. upper occupations

Fath. int. occ.

Fath. clerks

Fath. worker

Fath. retired

Fath. other occ.

Mother farmer

Moth. craft./ret.

Moth. upper occ.

Moth. int. occ.

Moth. clerks

Moth. worker

Moth. at home

Moth. other occ.

Monthly

income

(1993 french francs)

58,2%

22,7%

19,1%

47,6%

16,178

1,9%

9,8%

1

0

0

45.6%

16.02

1.7%

9.2%

0

1

0

51.5%

16.26

2.0%

10.0%

0

0

1

49.3%

16.56

2.4%

11.4%

52,3%

24,1%

23,7%

54,4%

23,3%

22,3%

63,1%

22,2%

14,7%

53,3%

25,2%

21,4%

52%

23,8%

24,2%

62,2%

20,9%

16,9%

63,7%

20,6%

15,8%

63,6%

21,0%

15,4%

50,0%

24,8%

25,1%

42,2%

33,2%

24,5%

14,5%

13.9%

15.5%

15.3%

17,0%

13,5%

26,7%

3,2%

14,6%

1,2%

3,7%

6,1%

14,5%

29,8%

4,4%

29,0%

11,8%

170

16.6%

13.4%

28.0%

3.3%

15.0%

1.3%

3.4%

5.6%

14.0%

29.2%

3.9%

31.0%

12.0%

144

17.8%

13.2%

25.5%

3.0%

14.2%

1.2%

4.0%

6.7%

16.2%

30.2%

4.6%

26.6%

11.0%

209

17.4%

13.9%

24.0%

2.9%

13.8%

0.9%

4.4%

6.8%

14.1%

31.1%

5.6%

25.6%

12.1%

202

61,0%

21,7%

17,2%

Family structure

Total

sample

(N=6534)

Type 1

Type 2