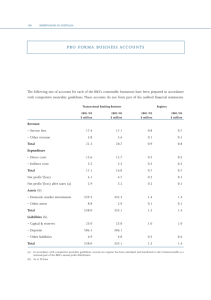

Regulatory intervention in the payment card industry by the Reserve Bank of

advertisement