Bankcard Association of Australia Response to Reserve Bank’s Consultation Document:

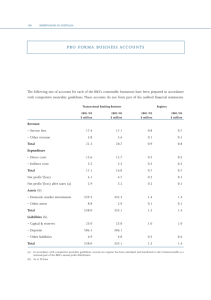

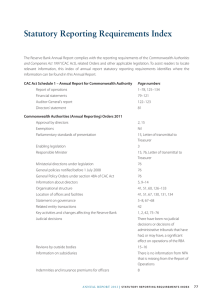

advertisement