Research Putting Science Practice

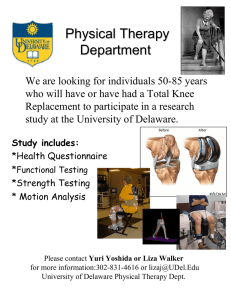

advertisement