The Mining Boom and the Australian Dollar Real TWI Model

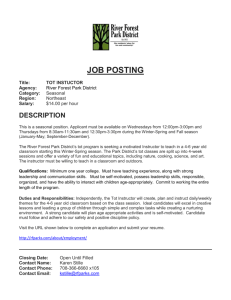

advertisement