Output Power Increase at Idle Speed in

Alternators

by

Juan Rivas

B.S., Monterrey Institute of Tech.(1999)

Submitted to the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science

in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of

Master of Science

at the

MASSACHUSETTS

INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY

June 2003

@

Massachusetts Institute of Technology, MMIII. All rights reserved.

Author

epartment of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science

une 1, 2003

Certified by_

David J. Perreault

Associate Professor of Electrical Engineering

Thesis Supervisor

Certified by_

Dr. Thomas A. Keim

Principal Research Scientist<,-L

oraqa'ty for Electromagiefl~i and Electronic Systems

hei~ervisor

Accepted by

Arthur C. Smith

Chairman, Department Committee on Graduate Students

MASSACHOSETTS lNSTTUf

OF TECHNOLOGY

0'-fioos

ww

JUL 0 7 2003

LIBRARIES

I

I

Output Power Increase at Idle Speed in Alternators

by

Juan Rivas

Submitted to the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science

on June 1, 2003, in partial fulfillment of the

requirements for the degree of

Master of Science

Abstract

The use of a Switched Mode Rectifier (SMR) allows automotive alternators to operate at

a load-matched condition at all operating speeds, overcoming the limitation of optimum

performance at just one speed. While use of an SMR and load matching control enables

large improvements in output power at cruise speed, no extra power is obtained at idle.

This document proposes the implementation of a new SMR modulation strategy capable

of improving output power at idle speed without violating thermal or current limits of the

alternator. The output power improvements at idle (with no cost increase) makes the use of

an SMR a more attractive option for the industry, and will facilitate introduction of the new

42V electrical standard in the near future. The proposed research will investigate the design

and realization of a suitable modulation strategy and will experimentally demonstrate this

new approach.

Thesis Supervisor: David J. Perreault

Title: Associate Professor of Electrical Engineering

Thesis Supervisor: Dr. Thomas A. Keim

Title: Principal Research Scientist, Laboratory for Electromagnetic and Electronic Systems

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Prof. David J. Perreault and Dr. Thomas Keim , my thesis supervisors,

for their patience, guidance, and support during the course of this journey. I have learned

a lot from them.

Thanks to Prof. John Kassakian for giving me the opportunity of conducting my research

at LEES - one of the greatest labs at MIT. I also thank Prof. Steve Leeb, Prof. George

Verghese, and Marylin Pierce, for their patience and support during my time at the Institute.

I'm also grateful for all the help provided by my colleagues and staff from LEES: Vivian

Mizuno, Wayne Ryan, Tim, Tushar, Rob 1, Rob 2 , Alejandro, Joshua, David, Frank, Ian,

Woosak, Kyomi, Karin, Gary. S. C. Tang, etc.

I would also like to thank the students that took 6.334 during the Spring semester of 2002

and 2003 for allowing me to learn from them.

I would also like to mention Dr. Javier Elguea (from Intelmex), Dr. Mayo Villagrain, Dr.

Sergio Horta, Dr. Jaime G6mez, and Dr. Carlos Reyes who motivated me to pursue my

dreams and professional goals. Worth mentioning are my Mexican friends at MIT: Antonio,

Chema, Ernesto, Gina, Jorge C., Marco E. Ulises, and Ray who supported me and never

stopped believing.

This work is also dedicated to my friends, Antonio Monterrubio, Arturo Castellanos, Edgar

Matamoros, Edgar Quintero, Eduardo G6mez, Jorge Andreu, Katty Ketlewell, M6nica

Carretero, Saul G6mez, Pilar Burguete, Steven Ketlewell, Tere Burguete, and Tofio Burguete for the life experiences we have shared. You all have played a great role in my life

and I could not ask for better friends.

To those that are not mentioned but contributed to this work.

To my uncle Enrique Rivas and my aunt Lilia Davila, two great relatives for whom I have

great admiration. They have always been a great source of advise and have pointed me in

the right direction.

I owe my deepest gratitude to my parents Carlos and Leticia, my siblings (also Carlos and

Leticia). Without their love and support I would not be where I am today.

-5-

Contents

1

2

Introduction

17

1.1

Introduction. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

17

1.2

Thesis Objectives and Contributions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

20

1.3

Organization of this Thesis

21

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Background

23

2.1

Introduction. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

23

2.2

Power Generation in Automobiles . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

23

2.3

Switched Mode Rectifier . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

28

2.4

Conventional Strategies for Increasing Output Power . . . . . . . . . . . . .

32

3 Increased Power at Idle

35

3.1

Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

35

3.2

Modulation delta . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

35

3.2.1

Analytical Model . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

37

3.2.2

Pspice Verification . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

39

3.3

Complete Modulation

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

40

3.3.1

Analytical Model . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

42

3.3.2

Pspice Verification . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

43

4, Modulation Parameter Selection

47

4.1

Introduction . . . . . .... . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

47

4.2

Thermal limits at obtaining extra output Power < Pot > . . . . . . . . . .

47

4.3

Full Grid Search over J and <D . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

48

4.4

Simulation over Vov . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

50

-7-

Contents

4.5

5

6

Simulation over

Vese . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

51

55

Experimental Results

5.1

Introduction ........................

. . . .. . . .. . . .

55

5.2

Alternator Parameters ..............

. . . .. . . .. . . .

55

5.2.1

Back EMF at idle speed . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

55

5.2.2

DC winding resistance . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

56

5.2.3

Winding Inductance . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

58

5.3

Implementation of the gating signals for the new modulation scheme

59

5.4

Experimental Measurements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

61

67

Conclusions and Future Work

6.1

Introduction ........................

67

6.2

Objectives and Contributions ..........

67

6.3 Future Work

68

...................

A Mathematical Analysis of the new modulation scheme

69

A.1 Introduction ........................

69

A.2 Analytical Model for the 6 modulation .....

69

A.3 Analytical Model for the

6 and 4D modulation .

77

81

B MATLAB Files

B.1 Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

81

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

81

B.3 MATLAB model for the complete simulation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

84

B.2 MATLAB model for the 6 simulation

C PSPICE Model

89

C.1 Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

89

C.2 PSPICE Library models . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

89

C.3 PSPICE model for the SMR . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

98

-8-

Contents

D FPGA implementation

103

D.1 Introduction ....................................

103

D.2 Implementation schematics

103

...........................

Bibliography

109

-9-

List of Figures

1.1

Historical and anticipated average electrical load in high end automobiles,

showing a continuous increase in electric power consumption from 1970 to

2005 [1] . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

18

1.2

Claw-pole alternator (Lundell machine) connected to a 3-phase diode bridge

19

1.3

Switched Mode Rectifier . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

19

1.4

Calculated output power of an alternator plotted as a function of the effective

output voltage seen at the alternator machine, and parameterized in speed.

The dashed locus represents load-matched operation, in which output power

is maximized at all speeds . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

20

Simple electrical model for the alternator-rectifier structure. The output

voltage is controlled by regulation of the field current flowing into the rotor.

24

Waveforms of alternator connected to a full diode bridge connected to a

constant output voltage. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

25

Output Power vs. Output Voltage in a typical alternator for different rotational speeds. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

28

2.4

Switched Mode Rectifier (SMR) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

29

2.5

Switching Function and Voltage phase to ground for the SMR . . . . . . . .

30

2.6

Output Power vs. speed using a Diode Rectifier and an SMR . . . . . . . .

31

2.7

3-phase Full wave inverter structure. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

32

3.1

Waveforms of alternator connected to SMR with an interval 5 introduced to

enhance output power at idle speed. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

36

Calculated Output Power vs. 6 and IARMS vs. 6 at idle speed using the

modulation 6 (V, = 14V). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

38

Calculated Output Power increase vs. 6 and I1RMS increase vs. 6 at idle

speed using the modulation 6 (V, = 14V). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

39

Comparison between the MATLAB and PSPICE models for power and current

vs. the control parameter 6. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

40

Waveforms for new modulation technique. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

41

2.1

2.2

2.3

3.2

3.3

3.4

3.5

- 11 -

List of Figures

3.6

Calculated Output Power vs.

4 and ILRMS vs. 4D at idle speed using the

new modulation. (f, = 180Hz, V,,8 = 14V, and, V0v = 20V)

3.7

3.8

4.1

4.2

4.3

4.4

. . . . . . .

44

Calculated Output Power increase vs. (D and IIRMS increase vs. 4 at idle

speed using the modulation. (f, = 180Hz, Vbae = 14V, and, V0V = 20V) .

45

Comparison between theMATLAB and PSPICE models vs. the control param.. ........ . . . . . . . . . . . . .. .. .

..

. . ......

eter ... .....

46

Measured power dissipation and temperature of a Lundell alternator running

at 1800 rpm and 3000 rpm. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

48

Simulated output power (W) vs.

6 and di for Vav = 20V, Vase = 14V at idle

speed (1800rpm ). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

50

Simulated RMS phase current (A) vs. 6 and 4 for Vv = 20V, Vbae = 14V

at idle speed (1800rpm). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

51

Output power increase (%) vs. 5 and l for V

= 20V, Va,, = 14V. Also

shown the locus on which the RMS phase current are 15% higher than regular

operating conditions. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

52

4.5

RMS phase current increase (%) vs. 6 and 4 for Vjv = 20V, V.,e = 14V. .

53

4.6

Output Power Increase (%) vs. 6 and P for V0, = 20V, V,ae = 14V when

4.7

4.8

phase current increase is limited to 15%. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

53

Simulated Pot, Pat increase, IaRMS and IaRMS increase vs. Vov for 6 =

18*, = 60*, V,aee = 14V . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

54

increase, IaRMS and IaRMS increase vs. Vbae for 6 =

18 0, 4 = 60P, V0v = 20V . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

54

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

56

Simulated Pa,, Pt

5.1

Prototype Setup

5.2

Harmonic Content of a Lundell alternator running at idle speed (1800 rpm)

and full field current (if = 3.6A). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

57

5.3

DC voltage vs. DC current through the alternator windings. . . . . . . . . .

58

5.4

Illustration of the modulation patterns of the SMR switches in relation to

the phase currents. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

60

Measured va,, and vj,ene waveforms for the alternator with modulation parameters 6 = 00, 4 = 0*, Voy = OV, Vbase = 14V, f, = 180Hz. . . . . . . .

61

Measured vag, and Vjense waveforms for the alternator with modulation parameters 6 = 130, D = 00, Vov = OV, Vbwe = 14V, fs = 180Hz. . . . . . . .

62

Measured vag, and VIe&e waveforms for the alternator with modulation parameters 6 = 10.8, D = 540, Vov = 20V, Vbaae = 14V, f, = 180Hz. . . . .

63

5.5

5.6

5.7

-

12

-

List of Figures

5.8

Experimental and simulated phase current ia at idle speed and maximum

field current. 6 = 11.30, 1 = 00, V 0 V = OV, Vs8 e = 14V. . . . . . . . . . . .

64

Experimental and simulated phase current ia at idle speed and maximum

field current. 6 = 15*, D = 53.80, VoV = 18.7V, Vbase = 14V. . . . . . . . .

64

5.10 Measured increases in output power and RMS phase current at idle speed

and full field current. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

65

A.1 Switched Mode Rectifier (SMR) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

70

5.9

A.2

Waveforms of alternator connected to SMR with an interval 6 introduced to

enhance output power at idle speed. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

A.3 One phase model of the SMR for calculating the phase current ia.

71

. . . . .

72

A.4 Equivalent model for one phase of the SMR for calculating ia. . . . . . . . .

73

A.5 vag shifted by

x

angle in order to make the signal an even function. . . . . .

73

A.6 Equivalent circuit model for the fundamental component one phase of the

SM R for calculating ial. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

75

A.7 Modulation 6 and d

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

77

Shifted version of the phase to ground voltage vag at the input of the SMR.

78

A.8

A.9 Equivalent circuit model for the fundamental component one phase of the

SM R for calculating ial. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

79

C.1

90

PSPICE circuit model for the SMR power enhancement modulation . . . . .

D.1 Full FPGA implementation

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

104

D.2 Block that generates the gating signals for one of the MOSFET'S for the SMR105

D.3 Block that generates the 6 interval for the new modulation

D.4 Block that generates the

. . . . . . . . .

106

4 interval for the new modulation . . . . . . . . . 107

D.5 Block that generates the PWM structure

-

13

-

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

108

List of Tables

4.1

Harmonic content of the back EMF generated by the alternator and used in

sim ulation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

-

15

-

49

Chapter 1

Introduction

1.1

Introduction

In recent years, there has been a continuous increase in the electrical power requirements in

automobiles. This increase is partially driven by a continuous introduction of new luxury

and performance-enhancing features in cars and also in part by the replacement of vehicle

functions originally powered by the engine. Today, car manufactures are looking for ways

to make those features to be electrically driven thus reducing the number of sub-systems

mechanically connected to the engine belt. Focusing on increasing efficiency an performance,

car manufacturers are looking for strategies that may improve the overall efficiency in order

to reduce the net car weight. This reduction in weight brings a significant increase in fuel

economy. The increase in electrical power that has resulted from these factors is illustrated

in Fig. 1.1, and power requirements may be expected to continue rising in the near future

[2].

The increase in the electrical needs in the automotive industry over time is also discussed

in [3]. The continuous electrification has challenged the mere existence of the actual 14V

electrical system in that the new electric requirements drive the current system closer to

its limit. This situation has incited a wide range of research efforts focusing on ways to

deal with the large power needs and the implications for future vehicles. These efforts have

lead to a growing worldwide consensus that a new higher-voltage electrical system is needed

[3, 4]. A whole new electrical system standard incorporating a 42V power system is under

development which will enable more power to be handled and will overcome many of the

practical limitations of the current electrical system.

In present-day cars a Lundell machine, or Claw-Pole (alternator) connected to a 3-phase

diode bridge transforms mechanical energy from the engine into electrical energy. Part of

the generated energy is stored in a battery that keeps the system voltage constant, and

supplies energy to diverse car systems when the engine is not running. Figure 1.2 shows

a simplified diagram of an automotive alternator. The output voltage is controlled by

adjusting the current through the field winding, which resides in the rotor. A pair of slip

rings are used to drive the current from the stator structure into the field winding.

-

17

-

Introduction

Projected trends in automotive electri"at system

3aOO

... .

.....

2500

1000 . . . . .

. ... ... ...

...

... .

50

196

1970

1975

1960

199

196

199

200

200

2010

Year

Figure 1.1: Historical and anticipated average electrical load in high end automobiles, showing a continuous increase in electric power consumption from 1970 to 2005 [1]

The electromotive force (EMF) generated by the alternator depends on both the current

present in the field winding, and the speed at which the alternator shaft is rotating. The

power delivery of the alternator-bridge structure is analyzed in [5] where a 3-phase rectifier

connected to a constant voltage load is modelled, after some assumptions and simplifications,

as a simple set of resistors. Using the aforementioned approach, we can obtain the output

power characteristics of an alternator whose output voltage is unconstrained (i.e. allowed to

vary with operating condition, as shown in Fig. 1.4). Today's 14V alternators are designed

to operate optimally at idle speed (- 1800 rpm) thus maximizing output power at the

speed providing the least power. At higher speeds, the power capabilities of the machine

are under-utilized. If this same alternator were to be used at a higher output voltage

(e.g. 42V) higher output power would be available at higher speeds, but no power would

be obtained at lower speeds.

A slight and inexpensive modification to the alternator-rectifier structure is described in

[6, 7] in which the bottom diodes of the rectifier are replaced by controlled switches (power

MOSFET's), as illustrated in Fig. 1.3.

This Switched Mode Rectifier (SMR) allows matching of the effective voltage seen by the

alternator to that required for maximum power at any speed. This operation, properly

called "load matching", permits the alternator to operate along the dotted line shown in

Fig. 1.4 that allows maximum output power operation.

-

18

-

1.1

Introduction

Figure 1.2: Claw-pole alternator (Lundell machine) connected to a 3-phase diode bridge

Field Current

Regulator

I

Field

b

ib

YLS

____

Vsb%

-

V

y

IYY

vsc%

Figure 1.3: Switched Mode Rectifier

The practical implications of such a SMR with load matching control are clear: the average

output power capability of the alternator over normal driving cycles is increased. Furthermore, the SMR allows and alternator machines designed for 14V to be directly employed

at higher voltages.

One limitation of an alternator using an SMR is that even though the alternator works

optimally at any speed, it does not improve the power availability at idle. Some present

and future installed functions in cars will require higher electrical power at cruise speeds

(electromagnetic valves, water pumps, etc. ) making the SMR a good solution for dealing

with that demand. On the other hand, many other applications will benefit from power

improvements at all speeds, including idle. Thus, the described approach is still limited by

the already-optimized-at-idle alternator. Design and control approaches which can improve

output power at idle are therefore of particular value for future systems.

-

19

-

Introduction

Alternator output power vs. V

0

400

3500 -

..

- ---

---

00rp

-.

.

3000

5000 rpm

-

250

i-

0 ---

200 0-

- 4000

-

150

rp

3000 rpm

100

0

p

-

50

10

15

20

30

25

35

40

45

50

55

V (V)

Figure 1.4: Calculated output power of an alternator plotted as a function of the effective

output voltage seen at the alternator machine, and parameterized in speed. The dashed

locus represents load-matched operation, in which output power is maximized at all speeds.

1.2

Thesis Objectives and Contributions

The primary goal of this thesis is to develop and experimentally demonstrate new control

laws for alternators with switched-mode rectification that provides increased performance

at idle speed. Analytical and numerical modelling methods are also introduced that allow

such control laws to be refined and optimized.

The existing load matching technique operates by modulating the SMR switches together

based on speed (and possibly other variables). This work takes the approach one step

further by allowing the three bottom switches to be modulated independently. Such a

scheme allows more power to be delivered at idle speed. Three important observations are

worth mentioning:

e The bottom MOSFETs of the SMR can only be effectively modulated while they carry

positive current; during other periods, their corresponding back-diodes conduct.

-

20

-

1.3

Organization of this Thesis

* Any viable scheme must keep the alternator within allowed thermal limits.

* For the modulation scheme to be practical given automotive cost constraints, it should

not require expensive sensors or controls.

There will be a focus on techniques that do not incur other costs (e.g. requiring position or

current sensors.)

It is expected that through the improved alternator performance that results from this work,

the use of an SMR will be a better, yet economical, option for high-power alternators. It

will also facilitate the introduction of the new 42V standard into the market by solving

some of the power challenges facing future vehicles.

1.3

Organization of this Thesis

Chapter 2 presents a background information on present technology automotive alternators,

and also presents some technologies developed to increase output power. A model which

describes operation with the SMR is also presented. Chapter 3 introduces a new modulation that makes use of the SMR to achieve an increase of the power available at idle speed.

Chapter 4 considers the practical implementation of the proposed modulation, starting with

proper PsPICE models that provide insight into the basic operation of this new technique.

Chapter 5 will analyze and compare the experimental results obtained with the setup with

both, the mathematical model and the PSPICE model. It also describes ways of characterizing and measuring the different parameters involved in a real alternator. The hardware

implementation and issues associated with the realization of the system are discussed. An

optimization on the output power under the constraints imposed by the conduction losses

will also be presented. Finally, chapter 6 summarizes the results of this thesis and suggests

directions for continued work in this area.

-

21

-

Chapter 2

Background

2.1

Introduction

This chapter provides some background information on power generation in automobiles

and also talks about different strategies being used in order to increase the output power

delivery at different speeds. In, addition the Switched Mode Rectifier (SMR) is introduced

and its advantages and shortcomings are discussed.

2.2

Power Generation in Automobiles

The Lundell alternator machine is a wound-field synchronous machine that has been widely

used in the automotive industry in order to provide electrical power to the different systems

involved in the operation of a modern car. In practice, the output voltage is regulated by

controlling the current flowing into the field winding which resides inside the rotor.

Figure 2.1 shows a simple electrical model for the Lundell alternator, which is modelled as

a Y-connected 3-phase Electromotive force (EMF) source followed by winding inductance.

These inductances, also called armature synchronous reactance, are relatively large and

dominate the dynamic performance of the electrical system. For simplicity the model does

not include any series resistance associated with the different windings, but they are also

a limiting factor in the amount of power that can be extracted from the alternator. These

resistances also impact the thermal performance of the machine and set the operational

limits for the maximum current that can be sustained. The alternator windings are then

connected to a bridge rectifier that provides a constant output voltage V which represents

the battery and the different loads connected to the electrical system.

Figure 2.2 shows the different waveforms for one of the phases at the input of the diode

bridge working at idle speed and connected to a constant voltage V(e.g. battery) at the

output. The waveforms are not drawn to scale and just provide an idealized representation

of the waveforms of interest.

-

23

-

Background

Fied Current

Regulatori

Figure 2.1: Simple electrical model for the alternator-rectifier structure. The output voltage

is controlled by regulation of the field current flowing into the rotor.

In particular, Fig. 2.2 shows the sinusoidal EMF voltages generated by the alternator with

a frequency w8 and a magnitude which is proportional to both the field current 'if and the

electrical rotational speed ws. In practice the current if is determined by applying a voltage

across the resistance of the field winding. The average field current is in turn determined by

-Ls

:s ib~)<

the average of a pulse width modulated voltage across this winding. The EMF generated

by the alternator is represented by the following expression:

VsV

Vsat)

=

VE MF sin(wst)

where,

VEMF

=

KMWSiJ

(2.1)

The same figure shows the phase current ia(t) that flows at the input of the rectifier structure. The voltage difference between the input of the diode bridge and ground is shown as

a square wave described by:

(V

0+

Vd

:

ia(t) >0(2)

which can also be mathematically described as:

vag(t)

[

+ VD]

Sfl (ia)

+ V

(2.3)

where V0 is a constant output voltage which represents the car battery and the electric loads

connected to it, and VD is the forward diode voltage drop. In the same equation sgn(x)

-

24

-

2.2

Power Generation in Automobiles

a

Vsa

Bottom diode 'off

Bottom diode 'on

/

Figure 2.2: Waveforms of alternator connected to a full diode bridge connected to a constant

output voltage.

represents the signum function.

It

is important to underline the fact that the fundamental component of the phase to ground

voltage

v,,g(t) shown in Fig. 2.2 is in phase with the phase current i,,(t).

Following the guidelines described in [5] it is convenient to represent the rectifier structure

connected to a constant output voltage in terms of the fundamental components of the

different waveforms involved in the operation of the system. Fundamental components

are the only ones that contribute to real output power (assuming sinusoidal back EMF

voltages). The aforementioned paper demonstrates that the fundamental component of one

of the phase currents (i.e. phase

a) has a magnitude Ialand phase a, relative to the back

EMF, described by the following expressions:

Ia, =

a

I"-

ae = tan- 11

where V,,g1

ag29

(2.4)

(2.5)

sa)

is the magnitude of the fundamental component Of vag(t). The magnitude of

this fundamental component is given by:

4

7r

Vag1 =

-

V

- +

2

25

-

Vd

( 2.6)

Background

Taking into consideration the rectified contribution of the 3 Y-connected EMF sources, it

is possible to find an appropriate expression for the average output power delivered to the

load. An expression for the average output power POUT is then:

POU.

1

= 3 VoVsa

ir wL,

2

(2.7)

sa

From equations 2.7 and 2.6 it can be appreciated that for any given alternator electrical

speed w,1, the output voltage can be selected in order to maximize the available output

power. By setting J, (POUT) = 0 and neglecting the forward drop at the diodes (e.g.

Vd = 0) we can find the output voltage V that maximizes the power delivered to the

output. The value of such output voltage V, is:

VO

=

maxPo

(2.8)

VaVaRMS

2

2 /zF

The condition in which the output voltage V is selected such that output power is maximum

at a given speed is properly called load matching.

Car manufacturers are presently constrained to one single output voltage, the bus voltage

(e.g. 14V in present day automobiles), thus the alternator design is optimized to work in

a load matched condition at a single speed. In particular car manufacturers design alternators that attain a peak operational performance at idle speed (~ 1800 RPM alternator

mechanical speed), because most of the actual electric loads will be running at all times.

Although it is true that there are electric loads that consume power which is proportional to

the car speed, many important loads require electric power to be provided by the alternator

at all operational speeds.

The angle a that exists between the EMF Va(t) source and the corresponding phase current

ia(t) in Fig. 2.2 can be related to the power factor. In particular, starting from equation

(2.5) we can express the tan 2 (a)as:

tan2 (a)=

Va

\Vagi

2

Now, using the trigonometric relation: tan

=

/

(2.9)

1

-

1 the power factor can be

'The electrical alternator speed and the mechanical alternator speed are related to each other by the

number of pole pairs in the alternator.

-

26

-

2.2

Power Generation in Automobiles

expressed with the following equation:

kpPF Cosa =Vagl

V aa

(2.10)

Figure 2.3 shows a plot of the available output power POUT vs. Output Voltage V, for

different speeds for a car alternator originally designed to operate at 14V output. The

same figure also shows lines along two operational output voltages, 14V and 42V, in order

to emphasize the difference in performance of the same alternator working at two different

operating conditions.

When operating at idle speed (~ 1800 RPM), the point at which the output power is

maximized occurs at an output voltage of around 14V. On the other hand, by holding the

output voltage at 14V and increasing the rotational speed, we can see that output power

also increases, but the alternator no longer works in a load matched condition. Now if the

same alternator were to be operated at a higher output voltage (e.g. 42V), the load matched

condition happens at a much higher rotational speed, specifically of around 4250 RPM for

this particular alternator. At this speed and output voltage, the alternator can provide

almost 2.5 times more power than using a lower voltage, but it is also evident that no

power would be delivered at lower speeds. This happens whenever the output voltage V is

higher than the maximum EMF voltage generated at any particular speed. This operational

characteristic is not acceptable for automobile applications because it is necessary to provide

enough electric power at all operational speeds.

If it is required to operate an alternator in a load matched condition, at idle speed, but

working at 42V output voltage, an alternative would be to rewind the alternator with three

times the number of stator winding turns, in order to stretch the horizontal axis of the

curve characteristics shown in Fig. 2.3, this would place the curve peak corresponding to

idle speed directly on the constant 42V voltage line. Because of the higher voltage, less

current would be required for the same output power than the lower voltage counterpart,

which implies that the 42V alternator requires three times the number of turns but wires

with just . of the copper area.

We can summarize the operation of a Lundell alternator connected to a constant output

voltage by making the following observations:

* Output Power is maximized at a single output voltage V, which if constrained to a

specific value (e.g 14V or 42V) implies that output power is optimized at a single speed.

" Unity power factor kp can't be achieved, because that would imply that V,. = Vag which

-

27

-

Background

Alternator output power vs. V

450

0

14V

42V

400 0-

6000 rpm

350

300 0

-

-

.6000 rpm

-

250

4000 rpm

0.CL

200

150 0.

3000 rpm

too

-.

..

. ...

.. ..

-

50

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

50

55

VX (V)

Figure 2.3: Output Power vs. Output Voltage in a typical alternator for different rotational

speeds.

when plugged into equation 2.7 results in zero total output power.

e For speeds w, different from the impedance-matched load condition, the alternator is

sub-utilized.

2.3

Switched Mode Rectifier

Realizing the fact that the alternator output power can just be optimized at a single speed,

a slight modification to the diode bridge structure was introduced in [61 in which the three

bottom diodes are replaced by active switches. Such structural change provide a new control

handle that allows to achieve a maximum output power in the alternator at all different

speeds. Figure 2.4 presents the aforementioned structure in which again the electrical model

does not explicitly show the series resistance associated with the copper windings.

In the Switched Mode Rectifier (SMR) the three bottom switches are modulated together at

a switching frequency that is many times larger than the electrical frequencies present in the

-

28

-

2.3

Switched Mode Rectifier

Fil Currnt

L

Feld

I .-

Ls

V

b___

Vsa

--

Vo

------------

Figure 2.4: Switched Mode Rectifier (SMR)

system (e.g. phase voltages and currents). This structure can be visualized as three boost

converters driven by the three-phase EMF sources, with a phase shift angle of 1200 generated

by the rotating alternator. With the synchronous reactance of each of the individual phases

of the Lundell machine taking the role of the inductors that store electrical energy in a

traditional boost converter.

The bottom switches are driven with a switching function that toggles between values one

and zero, with a duty cycle defined as d = t-, where T is the period of the switching signal.

Such switching function is shown in Fig. 2.5(a). With the described switching function it

is readily seen that for a positive current ia(t), when the switch is in the ON position, the

voltage Vag is zero (minus one diode voltage drop), and the upper diode remains reverse

biased. On the other hand, when the bottom switch is in the OFF position, the current

through the leakage reactance forces the upper diode to be ON, thus making the the voltage

Vag to be equal to the output voltage (plus one diode voltage drop). The voltage vag(t) at

the input of the switched mode rectifier is shown in Fig. 2.5(b) when ia(t) > 0. The local

average voltage (Vag) for ia(t) > 0 as a function of the duty cycle is:

(vag) = (1 - d) Vo

(2.11)

On the other hand, for ia(t) < 0 the current forces the the bottom diode to be in the ON

position, thus making the voltage Vag = 0 (minus one diode drop). So it is possible to

represent the voltage at the input of the SMR vag(t) as a square voltage in phase with the

current ia(t), having a high voltage equal to the local average for ia(t) > 0 of (1 - d)V and

zero when ia(t) <

0:

-

29

-

Background

q(t)

VAGMt

Vo-

-

- -- i

dT

T

dT

T

(a) Switching function q(t)

- -

VAM

T+dT

(b) Vg Voltage Phase to ground

Figure 2.5: Switching Function and Voltage phase to ground for the SMR

Vag (t)

=

(1

-

d)Vo + Vd

iai(t) > 0

Vd

:iai(t)

(2.12)

< 0

which is also represented as:

vag(t)

[(

O+

d)V +2 VD 1 sgn (iai)

-d)V

2

(2.13)

The duty ratio d can vary in range between 0 and 1. As implied by Eq. (2.11) this means,

that by controlling the value of d it is possibly to obtain any value of voltage (vag(t)) less

than the output voltage V. The magnitude of the fundamental component of vag(t) will

now a function of the duty cycle, and given by:

4 ((1 - d)Vo+V

d

Vagi = 2

7r

(2.14)

Plugging this new value of Vag, in equation (2.7), and again neglecting the forward diode

voltage drop, it is found that the output power for the SMR can be expressed as:

POUT-=-

3 VoVa

1

,r wL

-

(2(1 - d)V

7TrVsa

2

(215

The voltage V that maximize the output power delivery can be found to be represented by

the following equation:

-

30

-

2.3

Switched Mode Rectifier

Atternator Output Power vs. speed

SMR @ 50VX

4000

3500-

0

3000-

No extra power at idle

2000-

1500

I---

Diode @14V

-

- -

1000

15Mo

2000

2500

3000

3500

Alternator

4000

4500

5000

5500

6000

Speed (RPM)

Figure 2.6: Output Power vs. speed using a Diode Rectifier and an SMR

V

maxP

Vsa

ir

2/2(1d)

,rVsaRMS

(2.16)

2 (1-d)

Thus for a given V greater than the originals 14V the duty cycle d required to achieve a

load matched condition at any given speed is given by:

d

loadmatched

2r Vsa

= 1-

(2.17)

By operating the originally designed 14V alternator, with a SMR in a load matched condition, it is possible to obtain up to 2.5 times more power at higher speeds thus operating in

an optimal condition for all alternator speeds.

To demonstrate this potential, an automotive alternator was fitted with the proposed circuit,

and operated using the proposed control control law (Eq. 2.17) for a range of DC voltages.

The result, shown in Fig. 2.6, shows that at about 5800rpm and 50 volts, about 2.5 times

as much power is produced than with the same alternator at the same speed and at 14V

DC.

As indicated in Fig. 2.6, the use of a SMR does not improve the output power characteristics

of the alternator at low speed, specifically at idle. A significant advantage of implementing

the SMR is the fact that only minor changes have to be implemented to the conventional

-

31

-

Background

*F

=_t

lb

lo

*

+

V.

sytm ecuei

aciesice

r

rdrt

praei

eurd

Thos

d

ace

oa

s

Ice

condtio

ataO

sedsjs

he

ar1gon-eeecd"wihipsta

Figure 2.7: 3-phase Full wave inverter structure.

system, because in order to operate in a load matched condition at all speeds just three

active switches are required. Those switches are "ground referenced" which implies that

no complex drivers are needed in order to switch them between the "on" and "off" states.

Also, in order to control the SMR it is necessary to use information already available in the

car like output voltage and speed, so no expensive complicated sensors are required.

2.4

Conventional Strategies for Increasing Output Power

Other circuits and other control strategies have been used to increase the output power

of alternator systems. Among the most effective is the use of a 3-phase full wave inverter

structure (Fig. 2.7). With adequate DC-side voltage, this circuit can be used in a so-called

vector control mode to force the phase current waveform to be in phase with the back

EMF. For a given back EMF and phase current magnitude, such control maximizes the

delivered output power. This strategy has been proposed many times and implemented by

commercial companies like International Rectifier [8].

There are many drawbacks of this strategy as:

" The use of six active switches

" The high-side switches require isolated electronics, which tend to be expensive and complicated, in order to apply the correct gating signals

" The use of expensive current sensors and rotor position sensors is needed in order to

correctly implement the control pattern required by the active switches, although schemes

could potentially be designed that make use of simple sensors.

-

32

-

2.4

Conventional Strategies for Increasing Output Power

Another strategy proposed in order to increase the output power capabilities of a system

suitable to be used in automobiles is presented in [9], in which the same 6-switch active

bridge structure shown in Fig. 2.7 is used, but the number of current sensor is reduced by

the use of one simple position sensor which is utilized to detect a fixed point in the rotor.

With this information, the 6 switches are controlled at the same electrical frequency of the

system in order to artificially move the phase of the fundamental component of the current

to be closer to that of the generated EMF source. This approach results in an increase in the

available output power, but does not result in a load matched condition at any operational

speed but idle.

-

33

-

Chapter 3

Increased Power at Idle

3.1

Introduction

This chapter introduces two novel modulation techniques that effectively increase the output

power characteristics of an alternator considering the availability of a semi-bridge Switched

Mode Rectifier (SMR). The proposed schemes are simple and may be implemented without

the the addition of expensive sensors in a realistic implementation.

Based on the discussion presented in section 2.3 it was shown that even though an alternator

with a SMR and load-matching control provides almost 2.5 times more output power at

cruising speeds compared to an alternator with a simple diode bridge, no extra power is

obtained at idle speed.

To overcome the characteristic limitations of the load-matching technique, but keeping the

simplicity of the aforementioned SMR structure, a departure from the original control is

proposed. Instead of controlling the three active switches with the same duty cycle d, a

new degree of freedom is added to the scheme, by modulating the switches individually.

As will be shown, adding a new dimension to the control of the SMR, it is possible to

advantageously manipulate the state variables of the system. In particular one can modify

the magnitude and phase of the different harmonic components of the phase currents that

determine the average output power.

3.2

Modulation delta

One modulation technique that we use to increase output power is illustrated in Fig. 3.1.

The main goal of this simple modulation technique is to store electrical energy in the

machine inductance (L,) of each phase, during one part of the electrical period, to release

it in another part of the period. In order to achieve this goal, a time interval 6 is introduced

for each phase starting whenever the current of a phase becomes positive. During this

-

35

-

Increased Power at Idle

I

V

/

Vsa

/

ag

-

/

/

/

Vx

/

/

/

/

Il

64\

4-

/

\

/

\

/

Figure 3.1: Waveforms of alternator connected to SMR with an interval J introduced to

enhance output power at idle speed.

delta interval, the switch for that phase is held on (d = 1), while the other switches are

modulated normally. This action results in the application of the full back EMF source

across the winding inductance, which in turn stores additional electrical energy in that

inductance; this energy will be released in another part of the conduction cycle.

The modulation was selected because of its simplicity of implementation: implementation

only requires sensing the direction of the current. Such information is readily available from

voltage measurements done directly at the SMR.

Figure 3.1 shows the waveforms of one of the phases of the SMR with an interval of length

6 introduced whenever the phase current ia turns positive. vsa is shown as a dotted line,

while the current i, is shown as a distorted sinusoid as a solid line. The voltage at the input

of the SMR vag is also shown. The amplitude of vag named V, represents the local average

of the pulse-width-modulated waveform seen at the input of the SMR. The same figure also

shows the phase angle between vsa and i, denoted as a.

-

36

-

3.2

3.2.1

Modulation delta

Analytical Model

A mathematical model for the delta modulation is derived in appendix A. There, it is

shown that a considerable amount of extra output power can be obtained by changing the

length of the interval 8 shown in Fig. 3.1. The same derivation demonstrates that such

increase in real power is followed by a significant increase in phase current ia. The increase

in losses due to dissipation will ultimately set the limit for which this modulation will be

able to provide extra power at idle speed.

As described in the analytical derivation, we can find an expression for the magnitude and

the phase angle of the fundamental component of the phase current ia, labelled ial. The

fundamental component is the only frequency component of the current that contributes to

real power (given sinusoidal back EMF's). In order to find a closed-form expression for the

phase current, a symmetric conduction condition is assumed. Under this approximation,

a positive current iai is assumed to circulate through the alternator's winding for exactly

half of the current period (i. e. for 0 < wat < 7r). The positive conduction angle of the

current with the 6 modulation is not exactly 180 degrees in practice. While the symmetric

conduction condition is not exact, it does provide a good insight into the benefits of the

proposed modulation method. By applying this conduction condition, it is found that the

magnitude ial and the phase angle a that exists between the back EMF and the phase

current, can be expressed as a function of the back EMF amplitude Va, the synchronous

impedance Z. = R, + jw

0 L, expressed in polar form Z, = IZ, ILz (representing the series

resistance and inductance of the windings), the local average at the input of the SMR V,

and the control handle 6. In particular, the phase angle a between the back EMF and the

phase current can be expressed as:

a = Oz - sin-

cos

sin

+ Oz)

(3.1)

Also, the magnitude of the fundamental component of the phase current

ia1 is found to be:

(§ + 0)]

(3.2)

IalI=

[[cos (a - Oz)] - 2V cos (§) [cos

Using equations 3.1 and 3.2 we can express the average output power delivered ((POUT)) to

the load by calculating the real power delivered by the back EMF source and subtracting

the conduction losses occurring in the windings. The contribution of the other two phases

that constitute the alternator have to be taken into account in the calculation for total

power delivered. The equation for (PouT) is then:

-

37

-

Increased Power at Idle

Output Power vs. 5

1 2 00 .. .. .

1 1 50 - - -.

0

. . .. . . .

-.

-.-.-.-.-.

-

..

-.

-.

.

-

-

...

5

-

-

..-..-..-..-..-...-..- -

900 - -..--...--.

0

-

-

- -

-

-..-.. --.. . . . .. -. .. .

-

- .-..-.-.-.-

--

--

---

- -

. .. - .95 0 - -- -.

-.

--

.-

- - - - ---

-

-

- ---

-.

..

--..

..

.. .

1 1 0 0 - - - -01050 -

-

- . . . .. . . - . ..

10

20

15

25

8 (degs)

30

35

40

45

50

IRMS vs.8

80 - . . . .

0

5

-.

- -. . ...-.

-..

- ..

I

I

10

15

I.

20

(POUT) = 3

.

25

5 (degs)

Figure 3.2: Calculated Output Power vs.

modulation 6 (V2

14V).

[Vaiai

..

. .. .

-.

..

-.-.-.

30

co~t]-

. . . .

. .

40

45

35

3 and I1RMS vs.

.-.-.

..

3

. .

50

at idle speed using the

3 [RJai](.3

- 3.3 we can plot, the output power (POUT) as a function of the

control handle 65 (simulation file presented in appendix B.2). Figure 3.2 shows the average

Making use of equations 3.1

output power (PouT) and the RMS value of the fundamental component of the phase

current (iai). The circuit parameters used in this simulation (representing the components

shown for the model shown in Fig. 1.3) are: VsaRMS =10.716V, RJ = 37mQ, L.

120p.H

180Hz; where VSaRMS represents the back EMF at idle speed (e. g. electrical

and f8

frequency f8 180Hz) and full field current (e. g. if = 3.6A), and the control parameter

S was varied from 0 to 500, V4 = 14V. Furthermore Fig. 3.3 shows the percent increase in

output power and the percent increase in RMS phase current ia1, again as a function of 3.

As mentioned before, the increase in output power is accompanied by a corresponding

increase in phase current, which in turn increases dissipation in the machine windings.

This, in turn limits the maximum power increase achievable within the thermal limits of

- 38

3.2

Modulation delta

Percent increase in output power vs. 8

20

--

15

(D

Cz

- -.-

-

-. ..

-. ..

-.

-.

t 10

-

-.

-.

-

-.-.-.--.-.....

.....

.

5

00

10

5

15

25

20

30

S (degs)

Percent increase in

11RMS

40

35

45

50

vs. 8

0

40

-

- -.

-~

S30

~

-

--

..-.

. . -.

-

-

-

- .-.

.. .-.

-

-

-

-

-

..-..

-

.

- .....

-- -----.-.-.-.

-......

--

-..

-..

20

--

10

U""

0

5

10

15

20

25

S (degs)

30

35

40

45

50

Figure 3.3: Calculated Output Power increase vs. 6 and IARMS increase vs. 6 at idle speed

using the modulation 6 (V = 14V).

the alternator. The main advantage of this modulation technique is its simplicity, because

in a practical implementation the direction of the phase current ia can be easily obtained

from measured voltages at the input of the SMR.

3.2.2

Pspice Verification

In order to corroborate the validity of the mathematical model described in section 3.2.1

and Appendix A, a PSPICE model was developed for the system. A detailed description of

the PSPICE model can be found in Appendix C.

Figure 3.4 shows a comparison between the results obtained using the Pspice model and the

results presented in section 3.2.1. In particular it shows the output power (POUT) and the

approximate RMS phase current vs. the control parameter 6. The alternator parameters

used for the simulation are: VsaRMS = 10.716V, R, = 37mQ, L, = 120pH, f, = 180Hz

and full field current (e. g. if = 3.6A). Again, Rs is the winding resistance and L, is

the machine inductance. The results shown in Fig. 3.4 corresponds to a modulation such

-

39

-

Increased Power at Idle

Pout

o increase vs. 5

vs.

1200

1100-

15

-:1000

-o

OWM

S10

a-0

onb

5

900

[-800

--

- -

0

10

20

30

40

-- Matlab

Fia-

I

Ppice

50

0

10

MSI RMS

Mvs

I IRMS

20

30

Pspice

40

50

increase vs. S

iRMS

80

(D

40

1R

30

0

S60

MRla

.......

.....-.

50

F

210

-1

Mattab

0

10

2

20

30

40

--

- [-

~

-L

-=Pspice

40'

P sp....

50

0

10

20

30

40

50

Figure 3.4: Comparison between the MATLAB and PSPICE models for power and current

vs. the control parameter 6.

that V = 14V. The 6 control parameter is varied from 0 to 50'. From the figure it

can be appreciated that there is good agreement between the two models. The principal

differences between the models are because the analytical model considered here only takes

into account dissipation due to the fundamental component of the phase current, while the

circuit simulation incorporates all dissipation components.

3.3

Complete Modulation

Based on the encouraging results obtained from the models presented in section 3.2, an

augmented modulation is proposed in which additional control handles are added to the

modulation scheme. Figure 3.5 shows the phase current and the instantaneous phaseto-ground rectifier voltage for one phase over an alternator electrical cycle for the full

modulation scheme explored here. The switching function for each of the legs of the SMR

structure is realized at a frequency many times higher than the line-current frequency and

the duty cycle is modulated in such a way as to obtain the "local-average" phase to ground

-

40

-

3.3

Vsa

Complete Modulation

'D

\a

/

/

9

/D

v

\vBASE

\

2)r /

Figure 3.5: Waveforms for new modulation technique.

voltage Vag shown in Fig. 3.5. Looking at this local average voltage waveform it is possible to

define the different intervals that describe the modulation scheme. The back EMF voltage

Vsa is shown with a dotted line, while the current ia is shown as a distorted sinusoid with

a solid line. The pattern is the same for the other phases, but delayed by 120 electrical

degrees of the fundamental.

The complete modulation technique consists then of the following subintervals:

*

5 : During this sub-interval, beginning when the phase current becomes positive, the

switch is kept on, forcing the phase-to-ground voltage to be near zero. During this J

portion, additional energy is stored in the winding inductance.

Operation at a nominal duty ratio and local average voltage Vase. This

voltage is close to that for the load matching condition, and will be a function of the

alternator speed.

* Mid-cycle:

*

b : From the beginning of this interval to the end of the positive portion of the line

current, the duty ratio is adjusted so as to obtain an average phase to ground voltage

that exceeds the nominal Vase by V,, volts.

- 41 -

Increased Power at Idle

The modulation strategy embodied in Fig. 3.5 enables additional output power to be

obtained from an alternator as compared to that achievable with diode rectification or

switched-mode-rectification with load matching control. At the same time, this modulation

is also simple enough to be implemented with inexpensive control hardware and without

the use of expensive current or position sensors. As already mentioned, the zero crossing of

the phase current waveform can be effectively detected by observing the phase-to-ground

voltage during the FET off state.

By means of adding these new degrees of freedom in the control of the SMR, it is possible to

manipulate the state variables of the system beneficially. In particular we adjust the magnitude and phase of the different harmonic components that constitute the phase currents

to enhance the average power delivered to the output.

3.3.1

Analytical Model

As mentioned, this modulation introduces two new subintervals to the normal operation of

the SMR. The conduction angle interval 6 is introduced beginning when the phase current

becomes positive, during which the bottom switch of the SMR is kept ON, the effect of which

was already discussed in section 3.2.1. In the second new subinterval, a conduction angle

interval 41 is introduced during which the duty cycle of the corresponding bottom switch is

adjusted such that the local average of the voltage at the input of the SMR vag is set to a

voltage V0v volts higher than in the main interval. The net result of these two subintervals

will produce a phase shift that reduces the total phase angle a between the back EMF

voltage va and the fundamental component of the phase current ia1 thus increasing the

amount of real power obtained at idle speed (1800 rpm). Furthermore, these intervals can

be used to increase the fundamental phase current, thereby increasing output power. The

modulation strategy embodied by Fig. 3.5 achieves this within the modulation constraints

of the semibridge SMR, and without requiring detailed position or current information.

A detailed derivation that analytically solves for the magnitude and the phase of the fundamental component of the phase current ia relative to the back EMF can be found in the

appendix A.3. There it is shown that the angle that exists between the back EMF v.a and

the fundamental component of the phase current ia1, a depends in the values of the different

control parameters, namely: Vov, 8, 4, and V.se. The expression obtained through the

derivation is reproduced here:

a = 0Z + sin-[ cl sin (x - 6 - Oz)

1Va

-

42

-

(3.4)

3.3

Complete Modulation

In this expression, ci = al + b2 and x = tan. Where al and b, are the fundamental

sine and cosine coefficients in the Fourier series that describes the local average of the phase

to ground voltage Va. The series inductance L, and resistance R, that model the phase

impedance can be represented by a total series impedance described by its magnitude IZLI

and its corresponding phase 0,. The magnitude of the fundamental component of the phase

current under the same modulation scheme is is also repeated here:

-l-Cos

ci

(X - 5 - OZ)

|ZL|

|Iail = [ VaCos (a - OZ)

IZLI

(3.5)

Using (3.5) and taking into account the contribution of the other two phases it is possible

to obtain the same simple expression for the average output power (POUT) as in Eq. 3.3:

-3

(POUT) = 3 Vsalai c

[R,-

(3.6)

The influence of 5 in the output power and the phase current was already presented in

Section 3.2, so now we will focus attention on the influence that the new control variable

4 has on those two quantities. Figure 3.6 shows the output power obtained when just

the control variable 4 is applied. Again the conditions of the simulations are: VaRMS =

10.716V, R, = 37mQ, L, = 120piH and f, = 180Hz and if = 3.6A. The modulation

parameters for the simulation shown in Fig. 3.4 corresponds to V , = 14V, and VOV =

20V. The value of 5 is set to zero and the parameter D is varied from 0 to 700.

From Fig. 3.7, it can be seen that for small values of - a small increase in phase current ia

is accompanied by significant increase in output power. With bigger values of the control

parameter 4, it is possible to obtain a moderate increase in the output power but with

an actual decrease in the magnitude of the phase current. This implies that is possible to

obtain an increase in output power with lower conduction loss.

3.3.2

Pspice Verification

Fig. 3.8 shows the increase in output power (POUT) and the corresponding increase in RMS

phase current versus the parameter D using both the PSPICE averaged model the analytical

results presented in section 3.3.1. The results are qualitatively similar, though differences

are significant for larger values of 4. The difference that exists between the simulation

and the numerical predictions arise because interval 1b is not small, thus the symmetric

-

43

-

Increased Power at Idle

Output Power vs. 0

1400

130 0 120 0 - 0.a 1

1 00 -

0 100 0

- .

90 0 -

---..--.

-.--

..

-..

--

- - -.-- -- . ..

-.

.

-..

---.-

10

- -.-

30

-.-.

.-.--.-- --.-.

-

40

- -

----

--

- - --

-

-- -

20

. - -.-. - -.-.-

-.-

.

- -.-- - -.-- -. ..

.- -. .

. . . . ..-..

--

0

--

-

- - -

-

- --

- ----

50

-60

70

4D (degs)

11RMS vs. 0

65 - -

55

J 45 - -

0

-

-.-.-

.. .-..

10

20

30

40

-

-.. .

-..

. -..

-.-.-.

-.-.-.-.

-.-

-.-... .

..

-..-

..

.. . .

w0 --

- -.-

-. -.

.

50

.

- .-..-

-.-.

---.-.

60

70

4) (degs)

Figure 3.6: Calculated Output Power vs. D and IIRMS vs. <D at idle speed using the new

modulation. (f, = 180Hz, Vaae = 14V, and, VoV = 20V)

conduction condition is not achieved. From this figure it is also clear that the PSPICE

model also predicts operating conditions in which additional output power is expected at

lower magnitude of the phase current.

It has been shown that the new modulation technique allows additional output power by

proper control over the parameters 6, <b, V0 v and Vbase, it can be observed that the increase

in alternator output power is - for many modulation conditions of interest - accompanied

by an increase in power dissipation. So a compromise between extra power and extra

dissipation has to be reached that will allow the maximum amount of power while not

exceding the dissipation limits of the machine. A systematic search over the different

paramenters involved in the new modulation will be explored in chapter 4.

-

44

-

3.3

Complete Modulation

Percent increase in output power vs. 1b

-- -

-.

........

-.

-.-.-.-. ........

.-.-.-.........

-.

.-.-.--.~ ~-- --. ~

~- - ~ - .

.. ..-- ~- -~ ~

~ ~ ~-.-- ~ ....

- -- - - - - - ca 25

(D

0

.......

-.

.............

-.

.......... ..... ...20 ....... -.

- -- - - - -- -.-.-.

- .-.-.

--.

15

-.

-. -. -.....

-. .....

-.

...... .........

- - -.....

..

10

-.

...

--.

----.

...

-. ..

-.-.-.-.-.- . .............

...

.5

35

30

u

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

(D (degs)

Percent Increase in

11RMS

vs. D

20 F

- - -....

-.

-..

10

Zn

.. -.

--.

...

-.

-.

-.

-.-.-.

0

-.--.-..

-.-....

-.

--.

-.

-.- .....

-.

-

-20

0

-

10

20

--

-.

........

- .......

- --

.-

30

40

50

.-..-

.-.-..-..

.....

-.

...

-.

... -.-.--.-.-.--.-.-.......

..-.....-. .. -.-- -.

-10

-

60

70

0 (degs)

Figure 3.7: Calculated Output Power increase vs. <b and lRMS increase vs. <D at idle speed

using the modulation. (f, = 180Hz, Vase = 14V, and, V0V = 20V)

-

45

-

Increased Power at Idle

P

out

increase vs. 0

Pout vs. 0

1-4VU

35-

k

Matlab

Pspice

1300

3025

1200

CO

20

- - p--

.0

15

.. . ..- -.

.t

-

/

-

- -

-

01000

.. . .. .

.. . . . .

5

900

0

20

40

0 (degs)

0

60

20

IPincrease vs. 0D

IM

1

iRMS

- - Matlab

Pspice

do

20

10

40

0 (degs)

60

IiRMS IAMS vs

..

6560-

S-Matlab

Pspice

[

.....

55-

0

0)

-. -

-

1100

. .....

10

0

OF

- . . . -.-.

0-

- -..... -..

- - -- - - - 4-

0

-- --

-10

- -

-

0-

-

. .. . .. ... . .

-

-

---

40

- -

-

35

-20

-

- - -- - -

-

-.-

.

-

30

0

20

40

0 (degs)

0

60

20

40

0 (degs)

60

Figure 3.8: Comparison between theMATLAB and PSPICE models vs. the control parameter

4.

- 46 -

Chapter4

Modulation Parameter Selection

4.1

Introduction

This chapter addresses the selection of control parameters for the proposed modulation

technique. Practical constrains in selection of modulation parameters are described. Grid

searches over the modulation parameters(3, 4, VoV and Ve) based on averaged circuit

simulations are used to identify good parameter values.

4.2

Thermal limits at obtaining extra output Power < Pt

>

Based on the mathematical and circuit models presented in section 3.3, it can be observed

that the increase in alternator output power is - for many modulation conditions of interest

- accompanied by an increase in power dissipation. In particular, it was shown in section 3.3

that for increasing values of the parameter 6 (with others at nominal values) the dissipation

in the alternator windings will increase significantly. On the other hand, it was shown that

for changes in parameter 1 additional power can be accompanied by either an increase or

a decrease in winding currents and dissipation.

The alternator winding temperature increases with the square of the RMS phase current.

We can then infer that the amount of extra power that can be obtained through the proposed

modulation strategy is ultimately limited by the thermal capabilities of the electric machine.

Thus, it is necessary to properly adjust the modulation parameters in order to maximize

output power, while staying within the temperature limits of the alternator machine.

The power dissipation and the temperature profiles of an alternator are both a function

of the rotational speed. In particular Fig. 4.1 shows some experimental measurements of

the power dissipation and the stator winding temperature of an alternator working at full

output power and running at 1800 rpm and near 3000 rpm. In [10, 11], it is shown that a

typical alternator reaches a maximum temperature when running at 3000 rpm.

-

47

-

Modulation Parameter Selection

180-

3000

-2500

150;

W 2000

12001

-1500

90

0 1000

60

500

.

0

C.

0

E

30

C

1800

30Q

Speed (rpm)

0

.

Figure 4.1: Measured power dissipation and temperature of a Lundell alternator running

at 1800 rpm and 3000 rpm.

It can be seen in Fig. 4.1 that it is possible to increase the power dissipation at idle speed

(by using the proposed modulation for example) while not exceeding the normal operating

temperature of the alternator when the alternator is running at 3000 rpm. This suggests

that some degree of increased power dissipation at idle speed is permissible. In particular,

based on the thermal model described in [10, 11], at least a 15% increase in RMS stator current at idle speed is allowable from a thermal standpoint in a typical automotive

alternator.

Dissipation occurring in the alternator windings is proportional to iaRMS, which implies

that an increase in the RMS phase current of 15% corresponds to an increase in power

dissipation of 32%. Such an increase is permissible at idle speed because the resulting

temperature rise is still below that which occurs for operating conditions at higher speeds.

4.3

Full Grid Search over 6 and 1D

Given a limitation on RMS phase current, we can explore how the output power depends on

the different control parameters, and identify control parameters that provide the greatest

improvement in output power consistent with the thermal limits of the alternator.

We begin by exploring the response of the new modulation to parameters 6 and 4. The

-

48

-

4.3

Harmonic Component n

n = 1 fundamental

ni= 2

Full Grid Search over 6 and b

RMS Amplitude

10.716V

23.071mV

Phase

00

153.710

n=3

0.45689V

-16.0730

n= 4

n= 5

19.978mV

0.40452V

121.560

-166.8*

Table 4.1: Harmonic content of the back EMF generated by the alternator and used in

simulation

averaged PSPICE model (Appendix C) is a convenient way of exploring the performance of

the new technique for the different parameters involved. The simulation uses the following

parameters, based on measurements of an alternator: R, = 37mQ for the alternator stator

phase resistance, and L, = 120pH for the inductance (Fig. 1.3). The rotational speed of

the alternator was set to run at 1800 rpm (idle speed) which corresponds to an electrical

frequency of 180Hz. In real alternators, the back EMF voltage generated is not strictly

sinusoidal, but actually contains significant harmonic components. The harmonic content

of the back EMF of the alternator V.aRMS is characterized by the magnitude and the phase

at the different harmonic frequencies. The back EMF components used for the simulation

are shown in table 4.1 for idle speed conditions. The angle 6 was varied between 0* and

550, the angle D was swept between 00 and 900.

= 14V

Figure 4.2 shows the output power < Pot > obtained at idle speed when Ve

and VOv = 20V using the PSPICE simulation. It can be appreciated from the figure that

a significant increase in power can be obtained for different combination of 5 and 4. Not

all combinations of J and d shown in Figure 4.2 are possible, however, because of the large

increase in phase current which is incurred. Figure. 4.3 presents the RMS magnitude of

the phase current vs. operating condition. From the figure, it can be observed that the

magnitude of the current will either increase or decrease depending upon the value of the

parameters 6 and l selected.

The percent output power increase and the percent phase current increase predicted over

those obtained using load-matched control, are presented in Figs. 4.4, and 4.5. As mentioned

in section 4.2, the amount of additional output power allowed by using the new technique

presented here is bounded by the maximum permitted increase in conduction losses in the

alternator windings. Figure 4.4 also highlights the locus of operation conditions for which

the increase in RMS phase current is 15%. The limit in the increase in current was selected

in order to keep the alternator within acceptable thermal limits as explained in section 4.2.

As previously discussed, just the set of values of 5 and 4 for which the current increase is 15%

is of practical interest for the moment. In order to better appreciate the performance of the

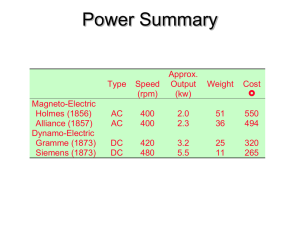

-

49

-

Modulation Parameter Selection

Output Power increase at Idle speed:- Vbase=1 4 , V0,=20V

1400

---

-.