The American Journal of Sports Medicine

advertisement

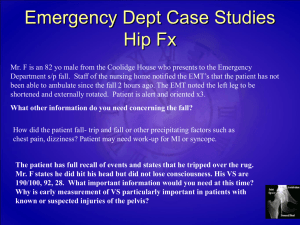

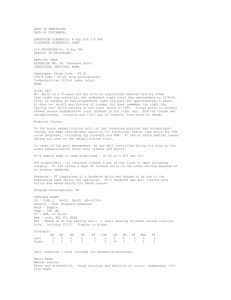

The American Journal of Sports Medicine http://ajs.sagepub.com/ Hip Joint Pathology as a Leading Cause of Groin Pain in the Sporting Population: A 6-Year Review of 894 Cases Alan T. Rankin, Chris M. Bleakley and Michael Cullen Am J Sports Med 2015 43: 1698 originally published online May 11, 2015 DOI: 10.1177/0363546515582031 The online version of this article can be found at: http://ajs.sagepub.com/content/43/7/1698 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com On behalf of: American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine Additional services and information for The American Journal of Sports Medicine can be found at: Email Alerts: http://ajs.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://ajs.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav >> Version of Record - Jun 30, 2015 OnlineFirst Version of Record - May 11, 2015 What is This? Downloaded from ajs.sagepub.com at UNIV OF DELAWARE LIB on September 8, 2015 Hip Joint Pathology as a Leading Cause of Groin Pain in the Sporting Population A 6-Year Review of 894 Cases Alan T. Rankin,*y MBBchBao, FFSEM(UK), MRCS, PGDip Sports Med, Chris M. Bleakley,z BSc(Hons), PhD, and Michael Cullen,y FRCP, FFSEM(UK and Ire), FISEM, MRCGP, Dip Sports Med, DCH Investigation performed at the Department of Sports Medicine, Musgrave Park Hospital, Belfast, Northern Ireland, UK Background: Chronic hip and groin pain offers a diagnostic challenge for the sports medicine practitioner. Recent consensus suggests diagnostic categorization based on 5 clinical entities: hip joint–, adductor-, pubic bone stress injury–, iliopsoas-, or abdominal wall–related pathology. However, their prevalence patterns and coexistence in an active population are unclear. Purpose: This study presents a descriptive epidemiology based on a large sample of active individuals with long-standing pain in the hip and groin region. The objectives were to examine the prevalence of key clinical entities, document coexisting pathologies, and present prevalence patterns based on key demographics. Study Design: Cross-sectional study; Level of evidence, 3. Methods: A retrospective review was conducted of clinical records of all hip and groin injuries seen between January 2006 and December 2011 under the care of a single experienced sports medicine consultant. In all cases, imaging was undertaken by a team of specialist musculoskeletal radiologists. Diagnoses were categorized according to 5 clinical entities using contemporary diagnostic nomenclature. The chi-square test was used to compare observed and expected frequencies across each subgroup’s prevalence figures based on sex, age, and sports participation. Results: Full medical records were retrieved from 894 patients with chronic hip and groin pain. The majority of patients were male (73%), aged between 26 and 30 years, and participating in footballing codes (soccer, rugby, and Gaelic sports) or running. A total of 24 combinations of clinical entities were found. There were significant differences (P \ .001) in prevalence patterns based on age, sex, and sports activity. Adductor-related pain or pubic bone stress injury rarely presented in isolation. Hip joint pathology was the most common clinical entity (55.98%) and was significantly more likely to present in isolation. The majority of hip joint pathologies related to femoroacetabular impingement (40%), labral tears (33%), and osteoarthritis (24%). These figures were significantly different across male and female patients (P \ .001), with a higher percentage of cases of femoroacetabular impingement and labral tears in male and female patients, respectively. Conclusion: Chronic hip and groin pain is often associated with multiple clinical entities. Hip joint pathology is the most common clinical entity and is most likely to relate to femoroacetabular impingement, labral tears, and osteoarthritis. These pathologies seem to be associated with secondary breakdown of surrounding structures; however, underpinning mechanisms are unclear. Keywords: groin; hip; athlete; sport; pain; entity Hip and groin pain is becoming a more commonly recognized problem in athletes at all competitive levels.19,21 This pain is often long-standing and continues to offer a significant diagnostic challenge10 for the sports medicine practitioner. Although it is acknowledged that there are various causes of chronic groin pain, until recently, there has been little consensus on the diagnostic criteria and nomenclature. Holmich10 originally proposed diagnostic categorization based on 3 clinical entities: adductor-related pain/osteitis pubis, hernia and lower abdominal pain, and iliopsoas-related pain. This was recently updated11 to include 2 additional *Address correspondence to Alan T. Rankin, MBBchBao, FFSEM (UK), MRCS, PGDip Sports Med, Department of Sports Medicine, Musgrave Park Hospital, Stockman’s Lane, Belfast, Northern Ireland BT9 7JB, UK (email: alanrankin@doctors.org.uk). y Department of Sports Medicine, Musgrave Park Hospital, Belfast, Northern Ireland, UK. z Faculty of Life and Health Sciences, University of Ulster, Northern Ireland, UK. The authors declared that they have no conflicts of interest in the authorship and publication of this contribution. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, Vol. 43, No. 7 DOI: 10.1177/0363546515582031 Ó 2015 The Author(s) 1698 Downloaded from ajs.sagepub.com at UNIV OF DELAWARE LIB on September 8, 2015 Vol. 43, No. 7, 2015 Sporting Groin Pain—Review of 894 Cases 1699 TABLE 1 Criteria Used for Clinical Entitiesa Clinical Entity Clinical Criteria Radiologic Criteria Adductor related Pain on palpation of adductor origin, pain on passive stretch. (Diagnosis based on presence of all clinical criteria independent of imaging.) Pain on hip extension stretch (modified Thomas test), pain on palpation and resisted hip flexion. ‘‘Clicking iliopsoas’’ also included. (Diagnosis based on presence of all clinical criteria independent of imaging.) Tender rectus abdominis on palpation and resisted sit-up. Positive ‘‘sportsman’s hernia’’—tender conjoint tendon, dilated superficial ring, pain and cough impulse on invagination of scrotum. Presence of inguinal or femoral hernia. (Diagnosis based on clinical criteria alone.) Tender over central pubic symphysis. Central pain on adductor squeeze. (Diagnosis based on presence of all clinical criteria independent of imaging.) Reproduction of pain and restriction during hip range of motion. (Diagnosis based on positive clinical criteria with positive imaging findings on radiographs or MRI.) Positive adductor pathology on MRI. Iliopsoas related Abdominal wall related Pubic bone stress injury related Hip joint related (intra-articular) MRI- or USS-positive iliopsoas bursa or pathology. Positive groin USS. (Imaging was used to support clinical diagnosis when clinical findings were not definitive.) Increased signal on MRI scan at symphysis. Positive radiograph or MRI. Relief of pain during intra-articular injection. (Injection is occasionally required to confirm clinical findings in the absence of imaging abnormalities.) a From Bradshaw et al,4 Holmich,10 and Holmich and Bradshaw.11 MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; USS, ultrasound scan. clinical entities: hip joint pathology and pubic bone stress injury (PBSI), a term that has superseded osteitis pubis to more accurately reflect the bony overload phenomenon noted in male athletes who undertake high training loads. Early studies suggested that incipient hernia13 and iliopsoas pathology10 were the most prevalent entities associated with long-standing groin pain. The advent of increasingly accurate magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and advances in hip arthroscopic surgery suggest that earlier studies may have overlooked the hip joint as a primary source of primary pain in the athlete.14 There is also an acknowledgment that multiple pathologies can coexist in patients with chronic groin pain,10 with hip joint pathology thought to be a major contributor to secondary breakdown of adjacent structures.5 No epidemiologic study has investigated the prevalence of hip joint pathology and determined the coexistence of other clinical entities based on contemporary diagnostic taxonomy. Our aim was to present a descriptive epidemiology based on a large sample of active individuals with longstanding pain in the hip and groin region. Our primary objective was to examine the prevalence of key clinical entities and document coexisting pathologies. We also examined prevalence patterns based on age, sex, and sports participation. METHODS All the cases reviewed for this study were based on patients who were seen at a single secondary-care sports medicine center under the care of a single sports medicine consultant over a 6-year period. Patients were either selfreferred or referred by physiotherapists, general practitioners, or orthopaedic surgeons. This is a general, public-access, sports injury service that sees a broad spectrum of athletes, varying from recreational to semiprofessional, across all age groups. The sports participants seen broadly reflect the types of sports practiced within the geographical region. As a secondary-care service, the majority of athletes would have sought treatment elsewhere, from physiotherapists or their own general practitioner, prior to referral to this service. The clinical records and radiologic reports were obtained for all patients whose cases were coded on the clinic’s electronic record system as ‘‘hip’’ injuries presenting as a new patient episode from January 1, 2006, to December 31, 2011. The following demographic data were obtained for each episode: age of patient at initial presentation, sex, and sports participation. All cases were deemed to be chronic or long-standing (.6 weeks)10 owing to the 10-week average waiting time from general practitioner referral to initial consultation at our clinic. Notes and radiologic findings were reviewed in combination to establish an injury diagnosis. Injuries were then subgrouped into 1 of 5 clinical entities using both clinical and radiologic criteria.4,10,11 All patients were under the care of a single sports medicine consultant with .20 years of experience in full-time sports medicine practice and an interest in athletic hip and groin pathology. All patients underwent appropriate imaging, and all studies were subsequently reported by a team of specialist musculoskeletal radiologists. A standardized systematic clinical and diagnostic approach, which can be viewed schematically in Appendix 1 (available online at http://ajsm.sagepub.com/supplemental), was used in the assessment of all cases. A single sports medicine doctor with experience in hip and groin injury Downloaded from ajs.sagepub.com at UNIV OF DELAWARE LIB on September 8, 2015 1700 Rankin et al The American Journal of Sports Medicine TABLE 2 Clinical Entity by Sexa 100 90 80 Entity alone Entity with others Male Percentage 70 60 Adductor related Iliopsoas related Abdominal wall related Pubic bone stress injury related Hip joint related 50 40 30 20 232 61 78 198 465 (22) (6) (8) (19) (45) Female 4 24 0 5 109 (3) (17) (0) (4) (77) 10 0 Hip Joint–Related PBSI Abdominal Iliopsoas-Related Adductor-Related Wall–Related Clinical Entity Figure 1. Interrelationships of common clinical entities. PBSI, pubic bone stress injury. This graph displays the percentage of each of the 5 clinical entities occurring either alone or in combination with other entities and will total 100% in each case. initially reviewed all clinical notes and investigations. Where any diagnostic uncertainty occurred, these cases were discussed and reviewed in conjunction with the senior author until agreement could be reached. If no diagnosis could be achieved, the case was labeled as ‘‘diagnosis unknown’’ (2 cases only). Statistical Analyses For analytic purposes, all diagnoses were initially categorized according to the 5 clinical entities summarized in Table 1. We calculated prevalence figures according to patient sex, age, and sports participation. Age was categorized into 5 subgroups (\18, 19-30, 31-40, 41-50, .51 years), and sports were categorized into 5 subgroups based on the 4 most popular sporting activities (rugby, soccer, Gaelic football, running) and ‘‘other’’ sports. The chisquare test was used to compare observed and expected frequencies across each subgroup. Significance was set at P \ .01. RESULTS Demographics In the study period from January 1, 2006, to December 31, 2011, full medical records were retrieved from 894 patients with hip and groin pain: 655 men (73.27%) and 239 women (26.73%). The modal age range was 26 to 30 years for men (154 cases) and 36 to 40 years for women (36 cases). The most common activities were soccer (37.5%), Gaelic sports (12.9%), and running (16.2%). Sporting activity was unknown in 7.9% of cases, with no regular sporting activity in 11.3%. Clinical Entity The 5 clinical entities proposed featured prominently in this cohort of patients; 84% of patients had at least 1 of these conditions. The breakdown was as follows: hip joint, a Data are presented as n (%); df = 4, x2 = 99.09, P \ .001. Percentages provided are expressed as a proportion of the 5 main clinical entities for both male and female and will total 100% for each sex. 398 cases (56%); adductor related, 236 cases (33%); PBSI, 202 cases (28%); iliopsoas related, 85 cases (12%); and abdominal wall related, 79 cases (11%). The range of diagnoses, not related to the 5 clinical entities, are presented in Appendix 2 (available online). A total of 24 combinations of clinical entities were found (Appendix 3, available online). Figure 1 shows the proportion of clinical entities presenting alone or concomitantly with others. There was a significantly higher-than-expected number of isolated cases involving the hip joint (233 of 398; df = 4, x2 = 233.2, P \ .001). There were few cases involving adductor-related pain or PBSI in isolation. A common pattern (observed in 22% of patients) was the coexistence of hip joint pathology, PBSI, and adductor-related pain. Prevalence Patterns Based on Sex, Age, and Sporting Activity Prevalence patterns by sex are shown in Table 2. Hip joint pathology was the most common diagnosis in male (45%) and female patients (77%). There was, however, a significant difference in prevalence patterns across sexes (df = 4, x2 = 99.09, P \ .001). Adductor pathology (22%), PBSI (19%), and abdominal wall pathology (8%) occurred much more commonly in men. There was a lower-than-expected prevalence of female patients with PBSI (4%) and adductor pathology (3%), and there were no cases involving the abdominal wall (Table 2). Table 3 shows that prevalence patterns also differed significantly across age brackets (df = 16, x2 = 58.4, P \ .001). Around 60% of cases of PBSI, adductor, iliopsoas, and abdominal wall pathologies involved patients in the 19- to 30-year range. The distribution of hip joint pathology was slightly more uniform; however, the most common age bracket to present (46%) remained 19 to 30 years. Just \40% of cases of hip joint pathology were in patients aged between 31 and 50 years. Adductor pathology, PBSI, iliopsoas, and abdominal wall pathology were rare in patients aged .51 years. We found a higher-than-expected number of younger patients with iliopsoas-related pain (14.5%). Table 4 shows prevalence patterns by sport. The majority of patients were involved in 1 of the common footballing codes (soccer, rugby, Gaelic sports) or running. There was a higher-than-expected prevalence of PBSI and adductorrelated pathology in soccer, rugby, and Gaelic sports. The Downloaded from ajs.sagepub.com at UNIV OF DELAWARE LIB on September 8, 2015 Vol. 43, No. 7, 2015 Sporting Groin Pain—Review of 894 Cases 1701 TABLE 3 Clinical Entity by Agea \18 y Adductor related Iliopsoas related Abdominal wall related Pubic bone stress injury related Hip joint related Other diagnoses 22 12 1 17 36 36 19-30 y (9.6) (14.5) (1.3) (8.6) (8) (33) 131 49 45 127 263 30 31-40 y (57) (59) (59.2) (64.5) (45.8) (27.5) 56 12 22 41 141 20 41-50 y (24.3) (14.5) (28.9) (20.8) (24.6) (18.3) 21 10 8 12 86 12 .51 y (9.1) (12) (10.5) (6.1) (15) (11) 6 2 2 5 48 11 (0.3) (2.4) (2.4) (2.5) (8.4) (10.1) a Data are presented as n (%); df = 16, x2 = 58.4, P \ .001. TABLE 4 Clinical Entity by Sporta Soccer Adductor related Iliopsoas related Abdominal wall related Pubic bone stress injury related Hip joint related 144 26 17 124 153 Gaelic Sports (58.5) (32.1) (56.6) (59) (39.9) 48 19 3 41 52 (19.5) (23.4) (10) (19.5) (13.5) Running Rugby 19 11 3 15 59 11 2 2 12 20 (7.7) (13.5) (10) (7.1) (15.4) Otherb (4.4) (2.4) (6.6) (5.7) (5.2) 24 23 5 18 99 (9.7) (28.3) (16) (8.5) (25.8) a Data are presented as n (%); df = 16, x2 = 79.4, P \ .001. Other sports: dance, triathlon, martial arts, hockey, swimming, tennis, athletics, cycling, cricket, general fitness training, walking, golf, badminton, trampoline, American football, squash, horse riding, skiing, motor cycling, basketball, ice hockey, ice skating, skateboarding, and rock climbing. b n=15 TABLE 5 Hip Joint Pathology: Specific Diagnosis by Sexa Diagnosis Osteoarthritis and arthritic change Femoroacetabular impingement Labral pathology Other Female Male Total 31 (28.0) 109 (23.0) 140 (24.0) 23 (20.7) 213 (45.0) 236 (40.4) 53 (47.7) 4 (3.6) 140 (29.5) 11 (2.3) 193 (33.0) 15 (2.6) OA and arthritic change n=140 Labral pathology a Data are presented as n (%); df = 3, x2 = 23.6, P \ .001. More than 1 diagnosis was possible per athlete for this analysis, resulting in n = 584 (compared to n = 574 athletes presenting with hip pathology of any cause). prevalence of hip joint pathology was higher than expected in all sports apart from rugby. Hip Joint Pathology: Specific Diagnoses Figure 2 provides a breakdown of the most common hip joint pathology diagnoses. Femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) of the hip joint (40%) was the most common diagnosis, followed by labral pathology (33%) and osteoarthritis (OA)/arthritic change (24%). Patterns of diagnosis were significantly different when they were compared across male and female patients (Table 5) (df = 3, x2 = 23.6, P \ .0001). Although the prevalence of hip joint OA and arthritic change was consistent across sexes, men were more likely to have FAI (45%), whereas women were more likely to have labral tears (47.7%). FAI n=193 n=236 Other Figure 2. Hip joint pathology: Specific diagnoses. Diagnoses under ‘‘other’’ included acetabular dysplasia (n = 7), Perthes disease (n = 3), avascular necrosis of the femoral head (n = 1), cystic fibrodysplasia of femoral neck (n = 1), synovial chondromatosis (n = 1), slipped upper femoral epiphysis (n = 1), and synovial cyst (n = 1). More than 1 diagnosis was possible per athlete for this analysis, resulting in n = 584 (compared to n = 574 athletes presenting with hip pathology of any cause). FAI, femoroacetabular impingement; OA, osteoarthritis. DISCUSSION Chronic hip and groin pain is a growing concern for medical practitioners. This study addresses the complex nature of pain presenting around the hip and groin region in Downloaded from ajs.sagepub.com at UNIV OF DELAWARE LIB on September 8, 2015 1702 Rankin et al The American Journal of Sports Medicine a large sample of athletes. Although previous studies addressed single clinical entities,6,7,17 to our knowledge this is the largest study providing a complete description of the pathologies involved in long-standing hip and groin pain. It is also one of the first to present a descriptive epidemiology using contemporary diagnostic taxonomy. Clinical Entities Holmich10,11 proposed diagnostic categorization of chronic hip pain based on 5 clinical entities: hip joint pathology, abdominal wall–related dysfunction, PBSI, adductor dysfunction, and iliopsoas pathology. We found this to be a useful diagnostic approach with .80% of our sample having at least 1 of these clinical entities. In contrast to earlier studies that cited incipient hernia13 or iliopsoas injury10 as the primary source of groin pain, we found that hip joint pathology was the most common clinical entity. This may relate to advances in MRI and hip arthroscopic surgery. Indeed, our findings align well with other smaller contemporary studies that identified hip joint pathology in approximately 50% of patients with chronic groin hip pain.4,7 Hip pathology was relatively more common in female patients compared with males. It was also shown to increase in both sexes with age, primarily because of OA. A nationwide survey18 in France found that 62% of athletes aged \50 years with hip pain showed degenerative radiologic signs, with 25% showing evolved hip OA. There are higher rates of hip OA in athletes participating in contact sports than in age-matched controls.16 Other cross-sectional studies showed that the risk of hip arthritis in former athletes is higher than that of age-matched controls (50-93 years).20,22 We found further evidence of close interrelationships among clinical entities. There was coexistence of 2 clinical entities in around half of our sample. Disentangling the interrelationships among various combinations of pathologies is challenging because of the large number of potential combinations. We identified .20 combinations of pathology in the current study. In conjunction with previous reports,5,7,11 we found a strong relationship between hip joint injury and secondary pathology involving adjacent anatomic structures. Of further interest was that few patients were diagnosed with isolated injury to the adductor, abdominal, or pubic region; this could suggest that hip joint pathology is implicated in the secondary breakdown of these surrounding structures. The causal mechanism is likely to vary according to the specific type of hip joint pathology, age, sex, and sporting code. Men composed .80% of the patients with longstanding groin pain. Others5,10 reported a similar sex disparity in the incidence of hip injuries. Of further interest was that PBSI, adductor pathology, and abdominal wall injury were extremely rare in our female population. This may relate to intrinsic factors, including sex-related differences in anatomy and biomechanics. Female athletes generally have greater laxity in their pubic symphyseal joints and may be more likely to dissipate force away from this region, minimizing the chance of overload.6,11 There are also commonly reported differences in lower limb biomechanics between male and female athletes.9,12,25 A key difference is the tendency for women to adopt greater hip adduction and knee abduction during sportrelated movements. These strategies may help to dissipate contact forces away from the hip, but a related caveat is the associated risk of serious knee injury. Iliopsoas pathology occurred predominantly in female patients, with the exception of adolescents. The iliopsoas hip flexor muscle seems to overwork and exhibit disproportionate myofascial tightness in those undertaking high physical loads in the presence of ligamentous laxity, which in the majority of cases are seen in female patients. In such cases, it may be associated with a clicking sensation1 when the hip extends from a flexed position, where the tendon crosses the iliopectineal line. Cross-sectional studies also reported a high prevalence of FAI in the athletic hip.7,18 We also highlighted a large number of FAI cases, with a higher-than-expected prevalence within our male cohort. Decreased hip range of motion has been shown to occur in Australian footballers with chronic groin pain.23 Despite some contradictory studies,24 it is becoming more accepted that hip pathologies such as FAI, while not necessarily the primary cause of groin pain itself, lead to a reduced range of hip motion.2 The prevalence of FAI in the athletic population is increased as compared with nonathletic controls.7 Laboratory-based studies have demonstrated how a reduced hip range of motion can lead to overload on central structures such as the pubic symphysis.3 A large percentage of our male cohort was involved in footballing codes that impose very wide amplitude movement on the hip. It is pragmatic to suggest that even a slight morphologic deformity could be enough to induce secondary pathology in this population. Abdominal Wall Injury We found abdominal dysfunction in just 11% of our sample, of which 70% had additional pathologies. Early studies13 suggested that incipient hernia is the most common cause of chronic groin pain. We acknowledge that differences in diagnostic approach and nomenclature can limit comparison across studies in this area. We used abdominal wall dysfunction to describe rectus abdominis dysfunction and pathology of the inguinal canal, be that conventional hernias or the so-called sportsman’s hernia.10,11 The sportsman’s hernia has been described by many names in the literature, such as athletic pubalgia,15 Gilmore groin,8 posterior inguinal wall dysfunction and tears of the inguinal ligament, external oblique aponeurosis, and conjoint tendon.11,17 Furthermore, imaging studies to diagnose these conditions are limited and may include subtle features on MRI scan, such a secondary cleft sign (present in adductor dysfunction and PBSI) and evidence of posterior inguinal wall dysfunction on dynamic ultrasound.4 Limitations and Future Study This review is based on descriptive epidemiologic data. Its retrospective nature is an obvious limitation; however, we must acknowledge that our data were collected prospectively, which limits recall bias. Our clinical observations Downloaded from ajs.sagepub.com at UNIV OF DELAWARE LIB on September 8, 2015 Vol. 43, No. 7, 2015 Sporting Groin Pain—Review of 894 Cases are pertinent and provide useful information for those aiming to discern the complex nature of hip joint pathology. We found further evidence that the differential diagnosis of hip pain is broad and can involve multiple pathologies. This was primarily an epidemiological study, based on clinical examination. We were able to group the athletes into 5 main clinical entities that have been previously described.4,10,11 Further study is needed to assess this clinical approach in the hands of other clinicians and in other populations before it can be adopted as a valid diagnostic approach. Disentangling the interrelationships among various combinations of pathologies is a challenge for future research. This should focus primarily on the high prevalence of intra-articular injuries and their effect on surrounding structures. In particular, prospective research should ascertain the extent that hip joint pathology leads to secondary breakdown of surrounding structures and delineate the underpinning causes. CONCLUSION This study provides a descriptive epidemiology based on a large sample of active individuals with chronic hip and groin pain. It reinforces the concept of categorizing chronic hip pain into 5 clinical entities. There is further evidence that hip joint pathology is the most common clinical entity associated with chronic hip and groin pain, with the majority relating to labral injury, FAI, and OA. These pathologies are linked to secondary breakdown of surrounding structures; however, the underpinning mechanism is unclear. Clinicians should be mindful that hip joint pathology is more common than previously recognized. It is also common for multiple pathologies to coexist. REFERENCES 1. Anderson S, Keene J. Results of arthroscopic Iliopsoas tendon release in competitive and recreational athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(12):2363-2371. 2. Audenaert A, Peeters I, Vigneron L, et al. Hip morphological characteristics and range of internal rotation in femoro-acetabular impingement. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(6):1329-1336. 3. Birmingham P, Kelly B, Jacobs R, et al. The effect of dynamic femoroacetabular impingement on pubic symphysis motion: a cadaveric study. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(5):1113-1118. 4. Bradshaw CJ, Bundy M, Falvey E. The diagnosis of longstanding groin pain: a prospective clinical cohort study. Br J Sports Med. 2008;42:851-854. 5. Branci S, Thorborg K, Nielsen M, Holmich P. Radiological findings in symphyseal and adductor-related groin pain in athletes: a critical review of the literature. Br J Sports Med. 2013;47(10):611-619. 1703 6. Fearon A, Stephens S, Cook J, et al. The relationship of femoral neck shaft angle and adiposity to greater trochanteric pain syndrome in women: a case control morphology and anthropometric study. Br J Sports Med. 2012;25(8):1080-1060. 7. Gerhardt M, Romero A, Silvers H. The prevalence of radiographic hip abnormalities in elite soccer players. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(3):584-588. 8. Gilmore J. Groin pain in the soccer athlete: fact, fiction, and treatment. Clin Sports Med. 1998;17:787-793. 9. Graci V, Van Dillen LR, Salsich GB. Gender differences in trunk, pelvis and lower limb kinematics during a single leg squat. Gait Posture. 2012;36(3):461-466. 10. Holmich P. Long-standing groin pain in sportspeople falls into three primary patterns, a ‘‘clinical entity’’ approach: a prospective study of 207 patients. Br J Sports Med. 2007;41:247-252. 11. Holmich P, Bradshaw C. Groin pain. In: Brukner P, Khan K, eds. Clinical Sports Medicine. 4th ed. Sydney, Australia: McGraw-Hill; 2012:545-578. 12. Landry SC, McKean KA, Hubley-Kozey CL, Stanish WD, Deluzio KJ. Neuromuscular and lower limb biomechanical differences exist between male and female elite adolescent soccer players during an unanticipated side-cut maneuver. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(11):1888-1900. 13. Lovell G. The diagnosis of chronic groin pain in athletes: a review of 189 cases. Aust J Sci Med Sport. 1995;27:76-79. 14. Malviya A, Stafford G, Villar R. Is hip arthroscopy for femoro-acetabular impingement only for athletes? Br J Sports Med. 2012;46:1016-1018 15. Meyers WC, Foley DP, Garrett WE, et al. Management of severe lower abdominal or inguinal pain in high-performance athletes: PAIN (Performing Athletes With Abdominal or Inguinal Neuromuscular Pain Study Group). Am J Sports Med. 2000;28:2-8. 16. Molloy MG, Molloy CB. Contact sport and osteoarthritis. Br J Sports Med. 2011;45(4):275-277. 17. Muschaweck U, Berger L. Minimal repair technique of sportsmen’s groin: an innovative open-suture repair to treat chronic inguinal pain. Hernia. 2010;14:27-33. 18. Nogier A, Bonin N, May O, et al. Descriptive epidemiology of mechanical hip pathology in adults under 50 years of age: prospective series of 292 cases. Clinical and radiological aspects and physiopathological review. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2010;96(8):S53-S58. 19. Orchard J, Seward H. Epidemiology of injuries in the Australian Football League, seasons 1997-2000. Br J Sports Med. 2002;36:39-44. 20. Schmitt H, Rohs C, Schneider S, Clarius M. Is competitive running associated with osteoarthritis of the hip or the knee? Orthopade. 2006;35(10):1087-1092. 21. Thorborg K, Holmich P. Advancing hip and groin injury management: from eminence to evidence. Br J Sports Med. 2013;47(10):602-605. 22. Tveit M, Rosengren BE, Nilsson JÅ, Karlsson MK. Former male elite athletes have a higher prevalence of osteoarthritis and arthroplasty in the hip and knee than expected. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(3):527-533. 23. Verrall G, Slavotinek J, Barnes P, et al. Hip joint range of motion restriction precedes athletic chronic groin injury. J Sci Med Sport. 2007;10(6):463-466. 24. Weir A, de Vos R, Moen M, Holmich P, Tol J. Prevalence of radiological signs of femoro-acetabular impingement in patients presenting with long-standing adductor-related groin pain. Br J Sports Med. 2011;45(1):6-9. 25. Zeller BL, McCrory JL, Kibler WB, Uhl TL. Differences in kinematics and electromyographic activity between men and women during the single-legged squat. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31(3):449-456. For reprints and permission queries, please visit SAGE’s Web site at http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Downloaded from ajs.sagepub.com at UNIV OF DELAWARE LIB on September 8, 2015