Up in smoke? Threats from, and responses to, on human development

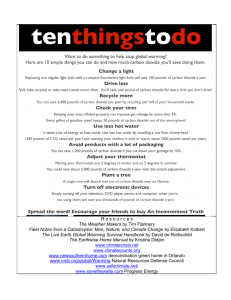

advertisement